Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Israel's ultra-Orthodox political parties are bracing themselves for a battle over who is to blame for the terrible disaster on Mount Meron last week.

Accusations will undoubtedly be hurled around in attempts to evade responsibility for the circumstances that led to the deaths of 45 people in a crush during the annual Lag BaOmer festivities at the site.

7 View gallery

Ultra-Orthodox mourners attend the funeral in Jerusalem for one of the victims of the crush at Mount Meron, April 30, 2021

(Photo: EPA)

The representatives of the ultra-Orthodox community in the Knesset have grown accustomed to constituents who do not hold them responsible for any ill. Nor does this sector favor commissions of inquiry, accepting of any fate as part of their belief in God.

But in the wake of the recent disaster, some Haredi Israelis are beginning to realize that the financial rewards that their MKs have long showered upon them are not enough.

In fact, they say, ultra-Orthodox legislators may have been doing more harm to their communities than good.

As the death of the victims was being mourned around the country, new voices began to emerge, calling last Thursday's tragedy a man-made catastrophe.

Fingers are being pointed at the various government agencies that signed off on the religious festivities and the police for restricting the movement of the crowds.

But for the first time, the politicians, their cronies and the lobbyists who have been wheeling and dealing at such events for years are also coming under fire.

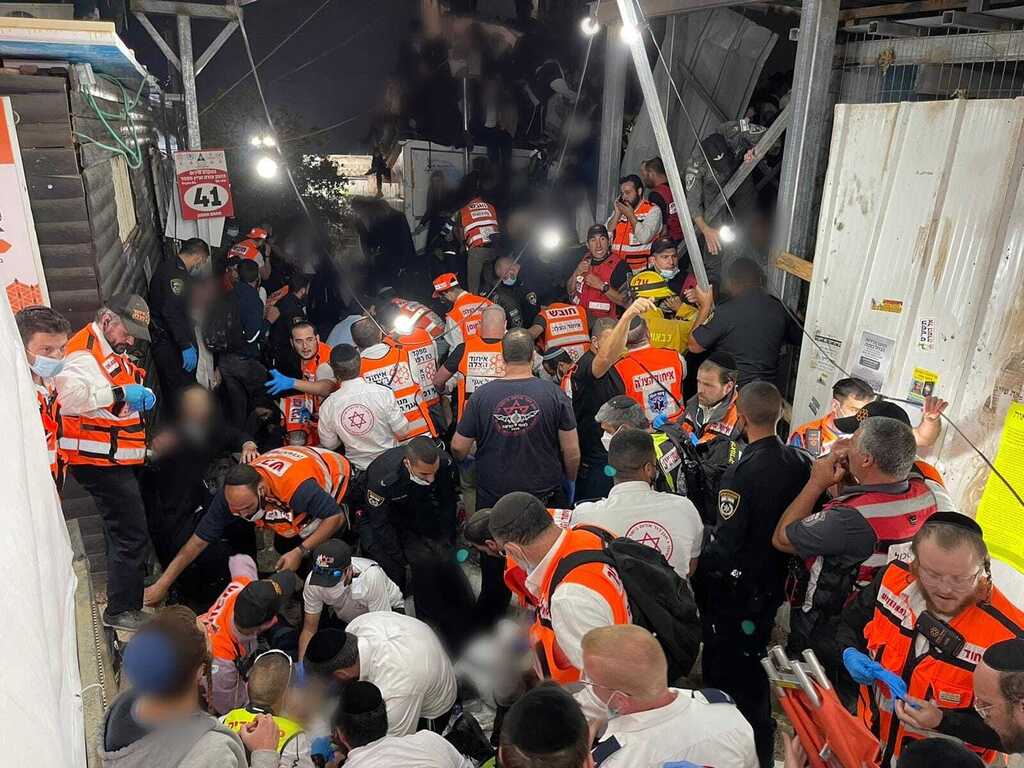

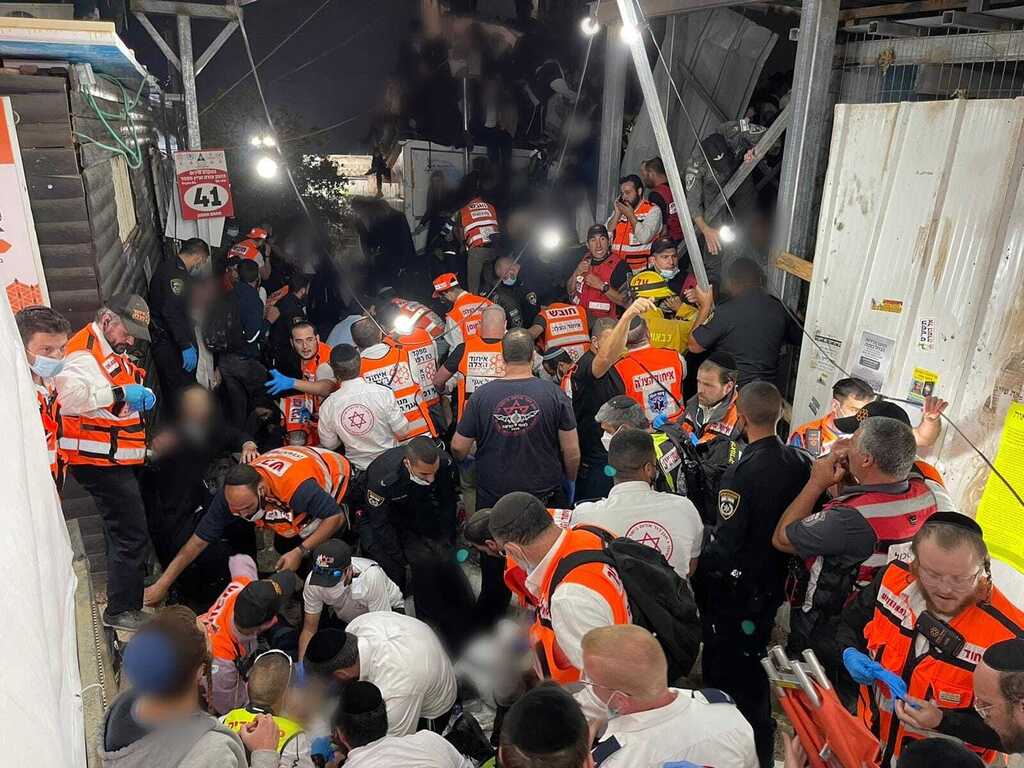

7 View gallery

Rescue workers from the United Hatzalah volunteer service treating the injured during the Meron disaster

(Photo: United Hatzalah)

"There is a lot of criticism," says Haredi advertising executive Shmuel Drillman, who spent an entire night attending funerals for victims of the disaster.

"I believe that ultimately some in the upper echelons of police and fire departments will lose their jobs and perhaps some politicians may have to leave the Knesset. But the problem does not begin with them, it begins with us."

"The machers (Yiddish for 'fixers') and our own organizations are where the problem lies, as well as in certain powerful Hassidic dynasties. But none of them will pay the price, we will not learn this lesson," he says.

"All we will do next time is have more emergency staff to deal with the injured and more people at the forensic institute to deal with the victims, so that we can bury our dead before Shabbat," Drillman says bitterly.

"That is how we do things."

7 View gallery

United Torah Judaism leaders Yaakov LItzman, left, and Moshe Gafni

(Photo: Gil Yohanan)

Araleh, a member of a large Hassidic sect, cannot contain his anger.

"Unfortunately, our community is run like the mafia," he says.

"I have stayed away from the festivities in Meron for years, ever since I was injured in the pushing and shoving of the crowds. Perhaps that saved my life because I realized back then how unsafe that place was during the holiday," he says.

"I hear many people wonder why soccer games at the stadium in Jerusalem, with 25,000 people in the stands, is safe; why there are multiple entrances and exits and everything is well organized. While in Meron, there are no limits on the number of people who can congregate and maybe two entrances to the entire site," Araleh says.

"You see the pictures of that passageway and it looks like somewhere in the third world. Like cattle being pushed on its way to the slaughter. Why?"

7 View gallery

Haredi men crowded together during Lag BaOmer festivities on Mount Meron before the disaster that killed 45 people

(Photo: AFP)

According to Araleh, it is not a question of money as the government provides plenty of funds to the community.

"Lots of money is being spent but not on the important stuff like infrastructure and safety," he says.

"Every institution must comply with regulations because there are codes and rules. But in the place where the greatest number of people congregate on one particular day, there is nothing. This is a colossal failure," he says.

7 View gallery

Personal effects of some of the victims lying on the ground after the disaster on Mount Meron last week

(Photo: AP)

"The state must be in charge," Araleh says. "It must end this chaos. It must tell the local organizers that Meron is not the property of the Hassidic sects.

"The state has the power to enforce the law. Sadly, that did not happen last week and now the Haredi community is beginning to understand that things must change," he says.

"Our ultra-Orthodox politicians are too strong, and the state is too weak to stand up to them," Araleh adds, accusing the sector's politicians of being "indifferent" to the danger of overcrowding at Meron.

"Anyone who was on Mount Meron in recent years, could see that the compound was too small to accommodate so many people and that it was a disaster waiting to happen. But no one cared," he says.

Eli Adler, an ultra-Orthodox lecturer on the Haredi community says that blaming the police is wrong.

"It's easy to blame them because they are not part of our community," he says.

7 View gallery

Ultra-Orthodox clash with police over violation of coronavirus restrictions in Ashdod in January

(Photo: Avi Rokah)

"There is animosity towards the police because of the clashes with law enforcement over coronavirus restrictions during the pandemic and now some see an opportunity for revenge," says Adler.

"But there are dozens of video clips showing the cops trying to help the people who were trapped and police officers pulling out bodies," he says.

The compound on Mount Meron is controlled by various religious endowments that for years have been left to their own devices without any real oversight.

"When the government tried to take control over the site, extreme factions objected because they did not want the area to become a stop on the evangelical tour of Israel, with women who are not modestly dressed walking around," Adler says.

7 View gallery

Tens of thousands of Ultra-Orthodox men attend the Jerusalem funeral of a rabbi that broke coronavirus restrictions, Jan. 2021

(Photo: EPA)

Adler believes that Haredi politicians bowed to the pressure by the extremists in their community, as they have always done, and foiled any government initiative.

"When there is no one specific authority in charge, there is chaos," he says.

"Haredi horse traders come up every year to pretend to prepare the site and fix whatever needs fixing. But when there is a problem, they claim it is not their responsibility. And since the disaster, those guys are nowhere to be found."

He says, however, that no one is really looking to these people for answers.

"It is easier to just blame the police."