Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Sitting in an antique armchair in the dappled light of his Renaissance-inspired West Bank mansion, Palestinian billionaire Munib al-Masri raised a subject that has angered him for eight decades.

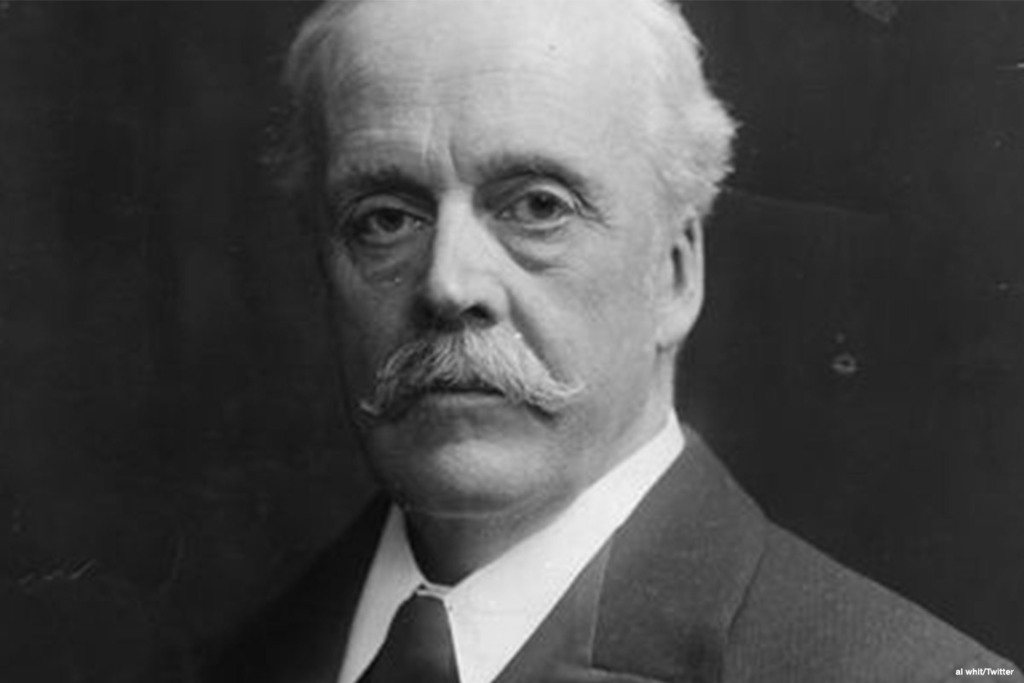

"Can you quote me the 58 words of Balfour's declaration?" he asked AFP, referring to the 1917 statement that set out London's support for a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

Sometimes referred to as the "Godfather of Palestine", Masri is the patriarch of a family empire that has interests in telecommunications, finance, industry and Palestinian real estate.

The 86-year-old lives alone in Beit al-Falestine (Palestine House), his mansion overlooking Nablus in the West Bank.

On display in the opulent home are photos of Masri with Nelson Mandela, U.S. presidential candidate Joe Biden and iconic Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, whom Masri smuggled from Jordan to Syria in 1970 in the boot of his car.

7 View gallery

Munib al-Masri stands in front his a photo with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat at a gallery dedicated for the history of Palestinians' struggle, at his mansion near Nablus

(Photo: AFP)

He has served as a minister in the Jordanian government and in the Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority.

But despite his financial success, political achievements and advanced years, Masri told AFP that he remains consumed by the declaration by British foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour, seen as a precursor to Israel's creation in 1948.

Political rights

The Balfour Declaration begins by stating that "His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object".

After the sentence was read to him, Masri said: "you forgot the main thing." He then completed the declaration himself.

"Nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine."

"That tells you that we have no political rights," Masri said.

Earlier this month, he and several activists filed a lawsuit in Palestinian court seeking compensation from Britain for the "wrongs" caused by Balfour.

7 View gallery

Munib al-Masri (C) flanked by activists gesture outside a court after filing a lawsuit against Britain over the 1917 Balfour Declaration in the West Bank city of Nablus

(Photo: AFP)

The largely symbolic gesture will almost certainly not force Britain to pay reparations, but Masri said filing the case fulfilled a childhood dream.

"I remember the day the teacher told us about the Balfour Declaration and its meaning," he recalled, perched next to his fireplace.

"I was eight years old. He read it and put it in my head. Since that day, I have been angry."

A big prison

The entrance to Beit al-Falestine includes a painting of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, hung across from a depiction of the Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem.

Masri said the latter image serves as a reminder that Arabs "knew how to build domes" before the Europeans.

The center of the building features a marble Hercules statue.

7 View gallery

Munib al-Masri poses for a picture in front of his mansion Beit al-Falestine (Palestine House) in the West Bank city of Nablus

(Photo: AFP)

There are also reminders of Palestinian setbacks, including frescoes of the "Nakba" (disaster) -- the Palestinian term describing Israel's creation -- and a portrayal of the "Naksa", the Arab defeat by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War.

"Today is the worst period in Palestinian history," Masri told AFP. "We live in a big prison."

7 View gallery

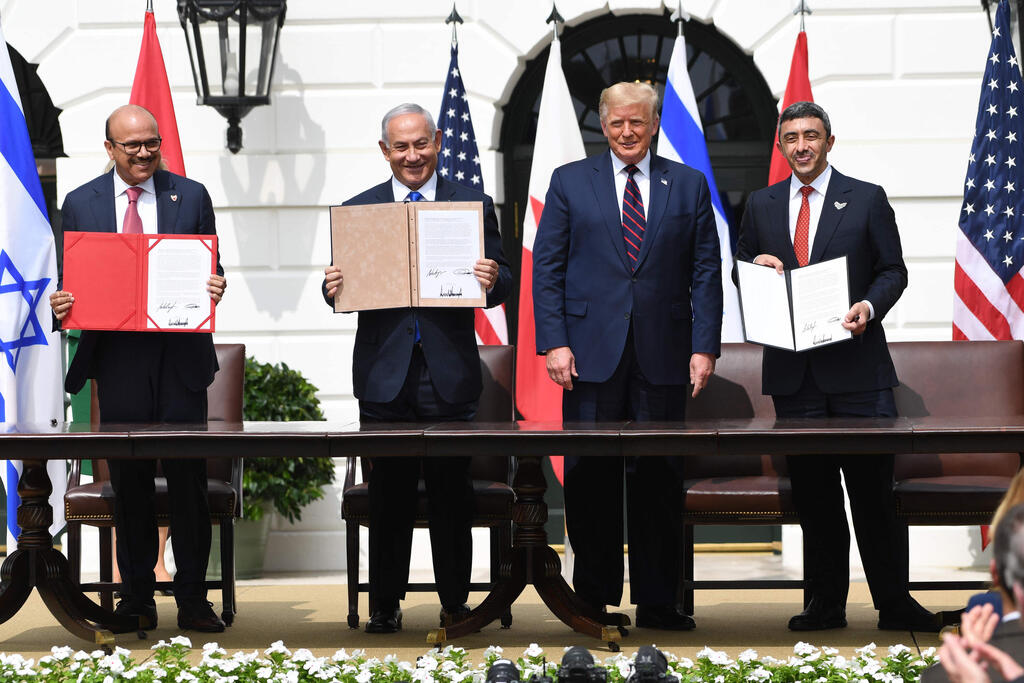

L-R: Bahrain FM Abdullatif al-Zayani, PM Benjamin Netanyahu, U.S. President Donald Trump, and Emirati FM Abdullah bin Zayed Al-Nahyan at the signing of the Abraham Accords at the White House

(Photo: AFP)

Masri also voiced concern over the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain establishing relations with Israel, which broke decades of Arab League consensus against normalization until the Palestinian conflict was resolved.

Masri's business interests include servicing Gulf oil companies.

Sudan has since said it will also establish ties with the Jewish state.

Share the cake

The father of six, with an untrimmed white beard, told AFP he had been enthusiastic about the Oslo peace accords in the 1990s but had since grown disillusioned.

He voiced hope that the Fatah movement of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas can reconcile with its rival, the Islamist Hamas, to give the Palestinians a united voice.

7 View gallery

Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. President Bill Clinton and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat during the signing of the 1993 Oslo Accords at the White House

(Photo: Reuters)

Masri's political influence has waned, but he still writes letters in Arabic to Donald Trump, encouraging the U.S. leader to change course in the Middle East, even if he has little hope of a reply.

But Masri's main frustrations lie with Israel.

He argued that Balfour gave the Jewish state a blank cheque to occupy and even annex Palestinian territory and that now Israelis, in control of the lands, refuse to "share the cake".