Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The Jewish concept of tikkun olam (lit. heal the the world) urges us to behave and act in a manner that benefits our surroundings, and that is the mission that David Abraham Walk undertook to give meaning to his life in Alaska.

"I came to work for the indigenous people that were living here before the Russians came, and their name is Tlinkit. They are coastal people who live off the tide," says the ultra-Orthodox Walk.

He believes the natives have taught him about the importance of culture and living in unity with nature while he has been able to share Jewish wisdom and the Torah.

"I think we all have the drive and the yearning to repair tears in the fabric of live that we see. So, I was a very young Jew coming to Alaska. I saw that the native peoples' interactions with the colonizing powers left many tears."

David Walk discusses life in Alaska

(Courtesy of the Ruderman Family Foundation)

David became a tribal judge for the Tlinkit and many other indigenous people in the vast state.

"For tikkun olam there was any number of things to throw myself into. And at that point in my life, the rights and the wellbeing of native people became my focus," he says.

Finding similarities between the history of the natives and that of his own people, David says he saw there was much he could do for the native Alaskans who felt comfortable with his knowledge of tribal law alongside an understanding of Western ways, and asked him to help set up the tribal court system.

6 View gallery

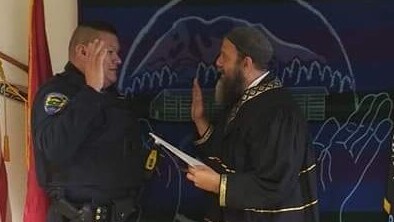

Tribal judge David Walk swears in a native Alaskan man during a court session

(Photo: Courtesy)

"I have been able to fly all over Alaska to these remote villages and in the winter the Inupiat Eskimo people would come and you get picked up in a snow machine moving 40 miles an hour across ice to get to the little house without plumbing," he says.

To Walk, performing a mitzvah in remote villages is a powerful feeling, and he says he is often the first Jew any of the local people have ever seen.

He has often been mistaken for a Russian Orthodox priest.

"People come up to me and begin confessing things I wish I did not know," he laughs.

"Of the two peoples on the earth [about whom] you can easily say: Yep that's a genocide, it's Jewish people and indigenous people. So, I am fulfilling my destiny as a Jew out in the wilds of Alaska."

Walker resides with his family in Sitka on the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

"We live in an amazing place," he says, detailing all the varieties of whales, sea lions and seals that inhabit the waters near his home.

There are, however, only 40 other Jews in his vicinity.

"We don't have a synagogue," he says. "There's lots of fish but no kosher supermarket or restaurant so there are a lot of obstacles and challenges.

Still, he insists on instilling in his family a life of faith and as much knowledge about Judaism and Israel as possible.

"We are a unique family here in Alaska and we call ourselves the frozen chosen," he says.

"I have taken it upon myself to raise observant Jewish children on an island with only 40 other Jewish people. I've tried to bring the warmth and the learning at home so that they are proud of their Jewish identity," he says, believing he and his family are in effect emissaries for Jewish people in their remote location.

Teaching about Israel has also become a personal mission.

"I have taken it upon myself to try to explain how amazing it is the rebirth of a nation and our historical connection to the land. And so, I seek to spread light and education and knowledge wherever I go about Israel and about our people," he says.

Walk, along with other Jews living in remote places, are part of a project that includes a new book called "50 States, 50 Communities," published by the Ruderman Family Foundation, which works to strengthen Israel’s relations with the Jewish community in the U.S.

The book gives inside glimpse into the everyday lives of the 50 Jewish communities of the United States, including those located in most isolated locations.

"The inspiring stories of David and many others prove that the Israeli public is not exposed enough to the great stories of the Jewish communities in the Diaspora,” says Ruderman Family Foundation President Jay Ruderman.

"Now that the coronavirus is forcing us all to isolate and with each community taking care of itself first, an important lesson arises here about how Jewish communities must cling to each other even in difficult conditions, no matter how isolated or distant from each other they may be.”