Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Israel on Thursday honored a Polish couple who hid Oscar-winning director Roman Polanski from the Nazis as a child, the Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem said.

The late Stefania and Jan Buchala received the Yad Vashem title of "Righteous Among the Nations" for those who helped save Jews during World War II.

"Despite their very difficult economic situation, the couple agreed to take in the Jewish boy as their own son, and keep him safe," Yad Vashem said.

The event, hosted at the House of Memory for Upper Silesian Jews in the town of Gliwice, was shrouded in secrecy to avoid any controversy or protests linked to Polanski, who has been sought by the United States for decades on rape charges.

The Buchalas' grandson accepted the medal in their name at the ceremony in southern Poland.

Sister Zofia Szczygielska, a Catholic nun who helped save many Jewish children, was also posthumously honored at Thursday's ceremony.

The controversial film director was just six years old when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, triggering the war and forcing the family into the Krakow Ghetto.

After his father smuggled him out through the barbed wire and got friends to take him in, Polanski was shuffled around, then sent to the Buchalas.

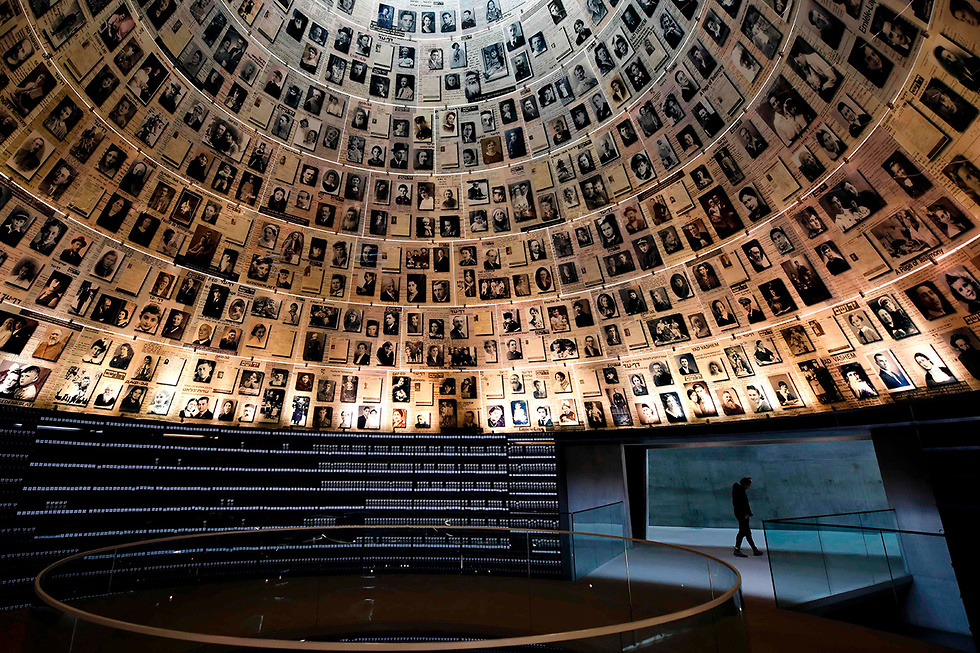

6 View gallery

Visitors walking through the Garden of the Righteous in Yad Vashem, honoring those of saved Jews from the Nazis during WWII

(Photo: Yad Vashem)

Devout Catholic peasants with three small children, they gave him shelter for nearly two years in the village of Wysoka, asking for nothing in return.

Polanski's mother, Bula Katz-Przedborska, was murdered at the Nazi death camp Auschwitz. His father, Maurice Liebling, was sent to the Mathausen concentration camp, which he survived.

The now 87-year-old French-Polish director of "Chinatown" and "Rosemary's Baby" recalled their "astounding" kindness in his autobiography, calling Stefania "strong", "energetic" and "sensitive".

'Heroic' grandparents

Polanski had tried for years to track down the family to thank them - to no avail. Both Buchalas died in 1953 and the village had no news of the children.

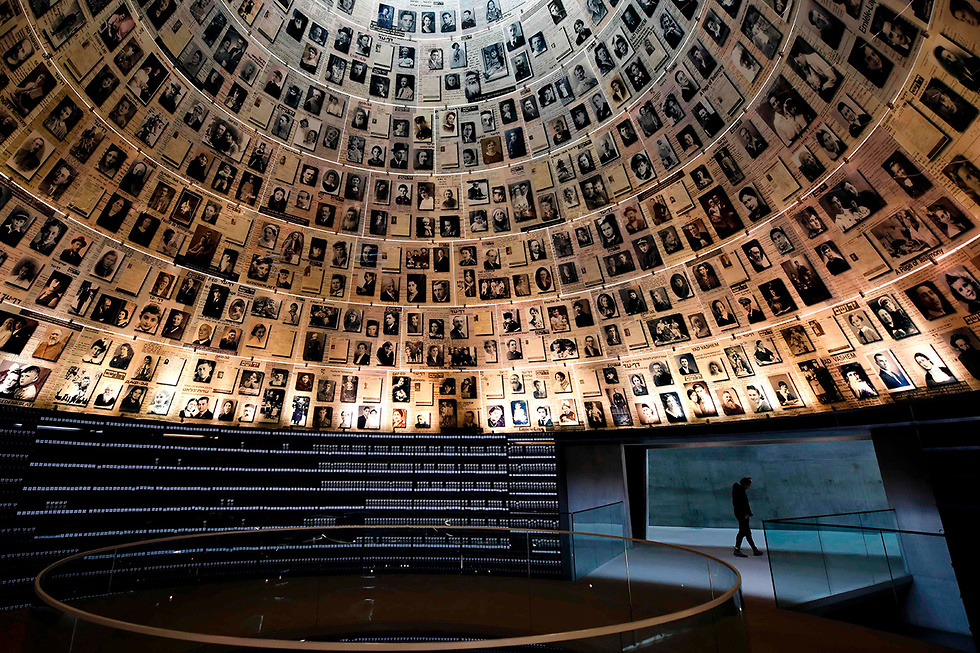

6 View gallery

The Hall of Names - a repository for the names of millions of Shoah victims at Yad Vashem

(Photo: AFP)

It was only in 2017 that Polanski came face to face with their grandson thanks to some detective work from the filmmakers behind "Polanski, Horowitz".

Due out next year, the documentary recounts the childhood years of Polanski and his lifelong friend and fellow Holocaust survivor, photographer Ryszard Horowitz.

Producer Anna Kokoszka-Romer recounted the first meeting between Stanislaw Buchala and Polanski when the grandson showed the director old photos.

"Polanski was moved. As for Stanislaw Buchala, you could see his joy at finally getting to learn more about his family," she told AFP.

His late father Ludwik had talked about growing up with a "brother" who moved to the U.S. after the war. Little did he know that his childhood playmate became filmmaker Roman Polanski.

Stanislaw, who is in his 60s, told the filmmakers he was proud of his "heroic" grandparents.

"People should know, especially now during the pandemic, that a person can do something selfless for another."

In his testimony to Yad Vashem, Polanski said Stefania Buchala "provided me with shelter, risking her own life and that of her family."

The stakes were high. In occupied Poland, even offering Jews a glass of water was punishable by death.

Poland, which lost six million citizens - half of them Jewish - during the war, has the most "Righteous Among the Nations" of any country, at more than 7,000 individuals.

For the rescuers

The filmmaker lives in France, as he is persona non grata in Hollywood and cannot return to the United States for fear of arrest.

Polanski pleaded guilty to unlawful sex with a minor in California in 1977, in a plea deal after he was accused of raping a 13-year-old girl. He fled the U.S. before sentencing.

Several other women have accused him in recent years of sexual misconduct, all of which he has denied.

Despite the allegations, Polanski won an Oscar in 2003 for directing World War Two drama "The Pianist" as well as a best director award at France's Cesar Awards in February that caused several women to walk out in protest.

The director of Yad Vashem's Righteous Among the Nations department, Joel Zisenwine, said "the award is given to the rescuers, not the survivor".

"It is about what they did in real time, risking their lives to save a nine-year-old child," he told AFP.

"Nobody of course has any way of knowing what happens to people as adults. It has nothing to do with that."