Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

IDF Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi predict that 2020 will bring Israel a high probability of war with Iran and its proxies on the northern border.

But 2019 was also considered to be a year with a high probability of war - in Gaza, in the south.

Yet that has not happened thus far, and in fact there is a real chance of an agreement being reached - flawed as it may be - between Israel and Hamas to ensure the southern border remains calm.

The chief of staff must always consider the glass half empty. That is his job and he must set goals for military preparedness.

Since the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Israeli forces were caught unprepared by the invading Arab armies, there has been a reticence to guess the enemy's intentions.

Kochavi, much like his predecessors, believes only what his intelligence agencies see and hear.

If for example, the enemy had developed advanced weapons systems and positioned them so that they posed a threat to regional stability, it is the military's responsibility to provide an adequate response as well as warn the civilian population of the existing threat.

That is exactly what Kochavi did when he presented his vision of the coming year in a much-reported speech last week.

However, the glass is also half full when considering the fast-changing political map of the Middle East and the repercussions such shifts are expected to bring.

2020 will be the year in which Syrian President Bashar Assad's regime is expected to retake control over rebel-held areas in the north of the country. It is also the year the Syrian ruler will lay the ground for rebuilding his war-torn country.

His challenges include solidifying his rule, attempting to reinstate Syria in the international community and receiving the much-needed funds from it.

By United Nations estimates, Syria will need $400 billion to rebuild vital infrastructure. This cannot come from one country alone and will require a coalition of countries able and willing to assist.

Since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011, Iran has supplied Syria with approximately $8 billion annually, but with U.S. economic sanctions on Tehran in place, the Islamic Republic will not be able to keep providing such sums.

The Russians, who are the dominant force in Syria today, are also hampered by their own financial situation.

Syrian oil is in the hands of the Kurds, Lebanese markets that in the past were open to Syrian goods are themselves financially ruined and the roads leading to the Turkish markets are closed.

Syria is being kept in a stranglehold and the threat of American sanctions on it is real.

One more "minor" challenge facing the Syrian regime is getting Israel off its back.

As long there is an Iranian presence on Syrian soil, Israel can be expected to launch attacks, thereby endangering the critical financial aid that Assad's regime hopes to receive.

Who would want to invest in a country that could soon become an arena for war between Israel and Iran?

Assad and his advisers know that Iran remains an obstacle to any serious effort to rebuild their country, even though it was the Iranians who stepped in to help during the civil war when the Syrian army fell apart.

Iran sent troops, weapons, advisers and militias - and of course Lebanese-based Hezbollah forces - to replenish Assad's troops.

4 View gallery

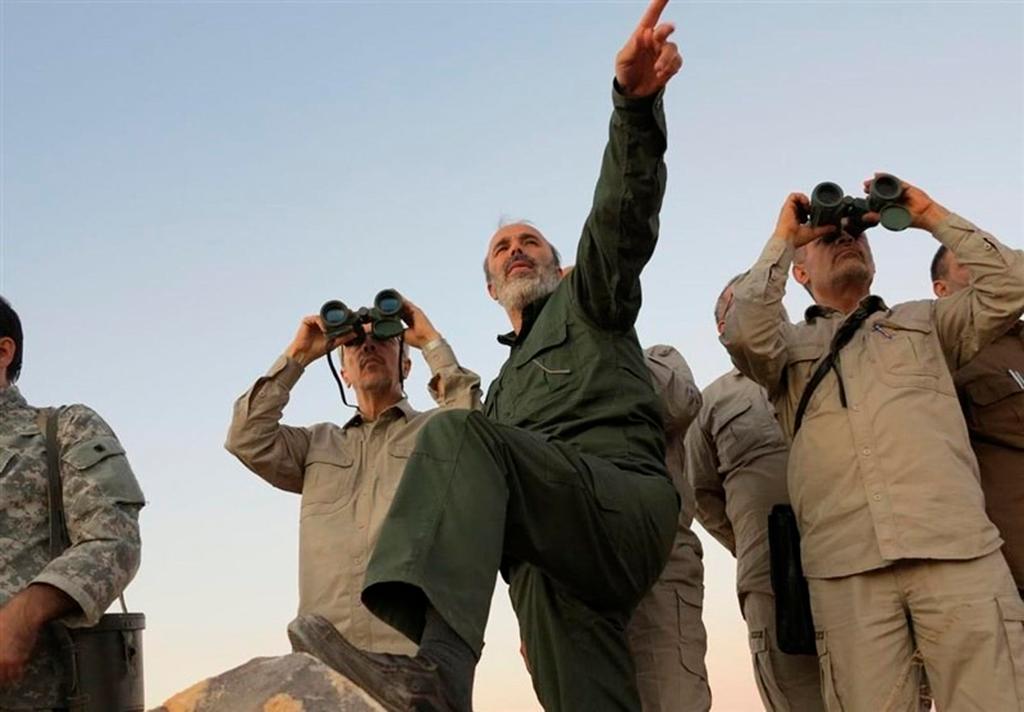

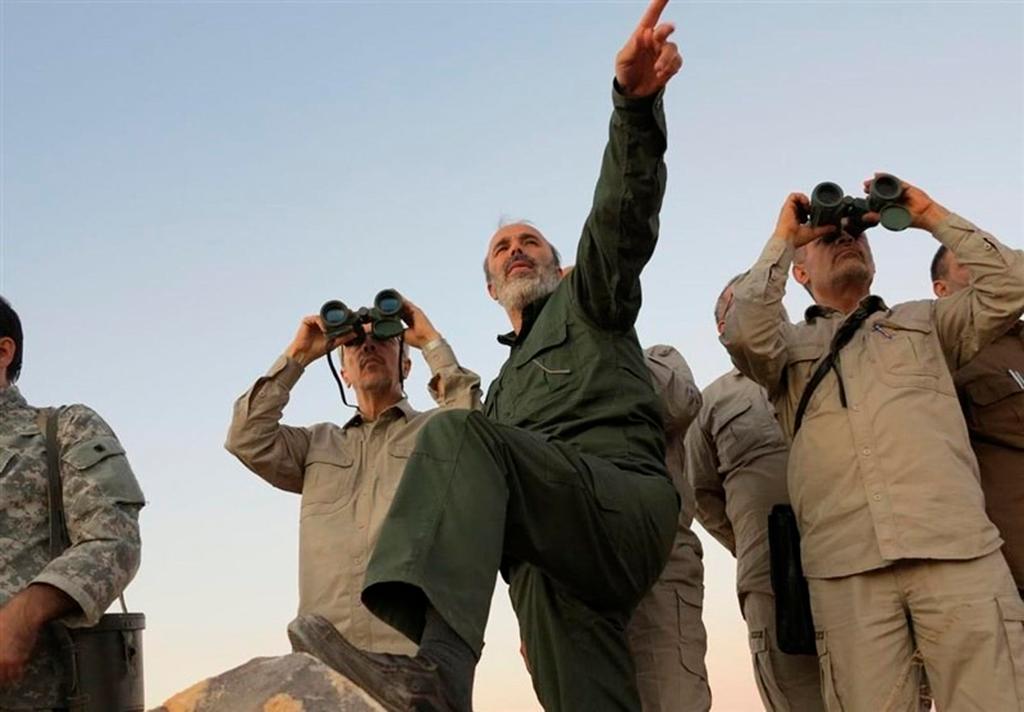

Iranian Chief of Staff Mohammad Bagheri, center, in Aleppo, Syria

(Photo: AP, Syrian Central Military Media)

But Iran's role in keeping Assad in power is over. It will now fight to hold onto its interests in Syria.

And the more Iran competes with the Russians over hegemony, the more its insistence on remaining in Syria threatens the flow of financial aid - and the less welcome it will be by the Syrians and the less of a threat to Israel it will become.

Even if an Iranian missile did (heaven forbid!) hit Tel Aviv in 2020, Israel would consider the attack to be an act of terrorism. And while a blow to morale, it would not be seen as cause to change Israel's strategic perspective - that Iran is losing its position as a central player in Syria.