Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The newly-elected Knesset will see a record-breaking number of legislators who hail from the religious Zionist sector of Israeli society, in numbers exceeding their size in the population.

They will represent a host of political parties that span the Knesset including Likud, Yamina, Blue & White, Yesh Atid and the New Hope Party.

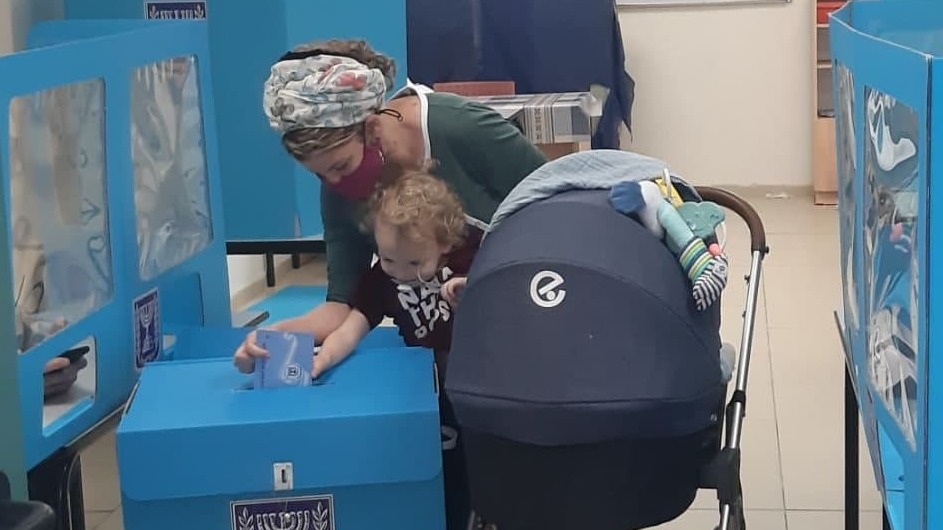

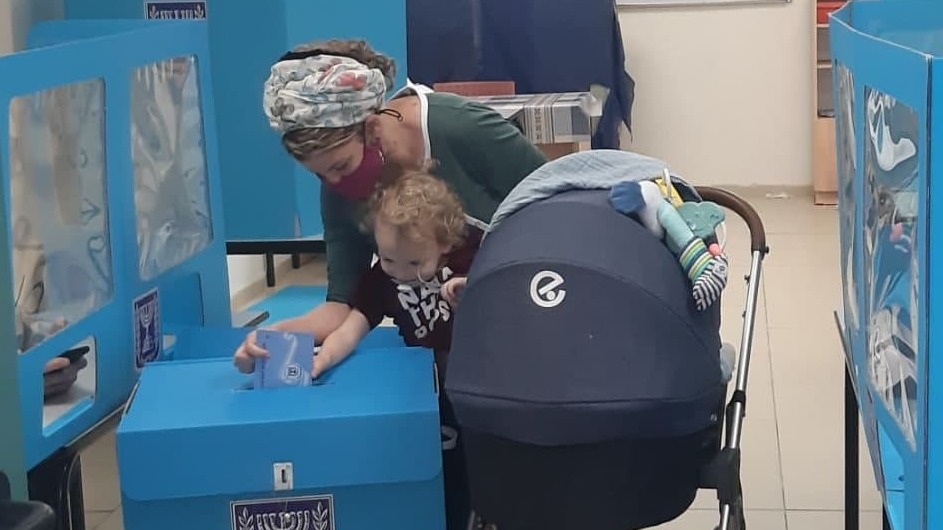

5 View gallery

A member of the religious Zionist community casts her ballot in the March 23 elections

Religious Zionist voters supported a variety of parties on Election Day. Some voted for ultra-Orthodox Shas and others for Labor, with a small number casting their ballots for the United Torah Judaism party.

But the brand of the religious Zionist electorate has been highjacked by one party and has become a code name for racism, misogyny and religious extremism.

Racist Itamar Ben-Gvir joined Bezalel Smotrich and others to form the Religious Zionist alliance. He brought an estimated 2.5 seats as his dowry. Smotrich targeted young Haredi voters and added perhaps one additional seat.

But it was Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who campaigned for the new alliance, carrying it over the minimum threshold into the Knesset, bringing homophobic, sexist extremists into the legislature.

Most religious Zionists are not extreme in their views. In fact, over the past few years there has been a shift in their perception about the role of women in society and its LGBT members, who are increasingly being accepted.

Unfortunately, many values that were held by this sector of the population through the ages have now been cast aside. Solidarity, caring for strangers and compassion for victims of abuse have all been neglected in the name of the settlement movement.

After Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, uprooting Jewish settlements in a traumatizing event, the importance of settling the "Land of Israel" became paramount — even if it meant excusing a multitude of sins.

5 View gallery

Soldiers remove young crying settlers from their homes as part of Israel's withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in 2005

(Photo: Avi Moalem)

The importance of the settlement movement was the motivation behind the religious Zionists' refusal to back Naftali Bennett and his Yamina party during Tuesday's election. Bennett — rightly or wrongly — was perceived to be preparing to join the left-wing bloc that opposes West Bank settlement.

Whether their vote was strategic or emotional, most religious Zionist voters are moderate people. But their ballots indicate that something deeper is taking place.

The Haredi settlers, those who proscribe to zealotry not only in their views on settlements but also in their religious practice, have shown a power that is disproportionate to their number in the religious Zionist community.

5 View gallery

Zealot settlers celebrating the brutal 2015 murder of a Palestinian family by extremist Jews

This power has more than a political component. These people are changing the sector's education systems, its youth movements and religious institutions.

While the first generation of the settlers was made up of moderately religious people, children who grow up in settlements today are taught a different and much more extreme form of Judaism and religious practice.

Every religious Zionist family either in a settlement or elsewhere today has at least one member who is part of the LGBT community or another who has become secular.

Young religious men and women are now remaining single into their 30s, unlike their predecessors, and there is less tolerance for domestic or sexual violence.

But Smotrich wants to change all that. He says that remaining unmarried is wrong and promises to pass a law that would make lodging complaints against sexual harassment much more difficult.

5 View gallery

The spiritual leader of the homophobic Noam movement Zvi Yisrael Thau attends a pro-Netanyahu demonstration in Tel Aviv in 2019

(Photo: Moti Kimchi)

The Religious Zionist alliance will oppose any moderate initiatives pertaining to religion and state, and its Noam faction has already declared it will wage war on LGBT Israelis and on feminism.

A confrontation with the existing values of the community will come sooner rather than later and domination by this new, regressive ethos will only push more religious Zionists into a secular life.

Although given the way the wind is blowing, that might not be such a bad thing.