Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

This covert plan, codenamed “Silver Plow,” was conceived in the initial days following October 7. The IDF Northern Command had completed its reservist call-up in a matter of days, and tens of thousands of soldiers had reported for duty on the Lebanese border in an effort to prevent Hezbollah from joining the Hamas attack.

Amid the uncertainty and deliberations within the general staff and security cabinet over whether to first act on the northern front against Hezbollah to thwart the anticipated attack or to focus first on Gaza, an unprecedented engineering operation was launched.

It aimed to reshape the sector and utilize each and every day of fighting to ensure that by the time calm returned, the border would look completely different. As security restrictions on border communities were lifted and evacuees returned, the IDF stated that with regard to the borderline, on both the Israeli and Lebanese sides – Mission accomplished.

For over a year, in what became one of the IDF’s most complex engineering operations, thousands of engineering and infantry soldiers shaped the new border of diverse terrain along more than 120km stretching from Rosh Hanikra to Har Dov.

Hezbollah had spent decades constructing terrorist compounds in buildings, forests and underground infrastructure along the entire border as part of Nasrallah’s plan to conquer the Galilee. Now, the IDF sought to ensure that the entire border zone, including a few dozen kilometers into Lebanese territory, would be cleared and barren.

Back to the Second Lebanon War

Until the early hours of last Tuesday, when the IDF completed its withdrawal from south Lebanon (with the exception of five strategic points within Lebanese territory), IDF engineering personnel were still pulling up trees and clearing the thicket overlooking Israel’s northern communities.

“We divided up the border into sections and broke down each sector based on its topography and the type of engineering work it required,” says Northern Command Chief Engineering Officer, Col. I. Back in 2006, as a young officer, he had fought in the Second Lebanon War. When he withdrew with the troops after 36 days of fighting, he felt a sense of frustration knowing the task had not been completed. This time around, he means to finish the job.

“Back in October 2023, when the war kicked off, we brought in geologists, engineers and earthworks experts to provide solutions for the forests, wadis, buildings and underground infrastructure we knew we would encounter during the mission,” says Col. I. For almost a year, up to September 2024, the IDF didn’t know whether or not there would be a ground operation into Lebanon or what would come of the engineering efforts to avert a ground incursion.

“Our operational priorities rested on firstly addressing the areas facing civilian communities,” says Col. I. This was to prevent Hezbollah from preparing itself in the dense forested areas so as to infiltrate Israel under the cover of the thicket. Working methodically, engineering forces continued addressing operational weak points such as wadis serving as potential infiltration routes.

At some stage, the IDF gave up on waiting for an IDF ground operation into Lebanon. Each night, under the cover of darkness, armored engineering vehicles would work beyond the Blue Line, and were later joined by lighter armored vehicles for covert operations that were conducted with artillery back-up.

Since the war started, 300 military and commandeered civilian mechanical engineering equipment vehicles, joined by four engineering battalions - some brought in from other sectors - have been working away along the border, invariably under fire and anti-tank missile attack. And soldiers have been wounded.

"We stretched our engineering capabilities to the limit while, at the same time, supporting the ground operation troops."

The operation’s turning point came as the ground operation into Lebanon kicked off October 2024. “Once we attained operational control of the sector, we stopped our ‘regular’ work and went in with full force. We drafted hundreds of reservist engineering soldiers and civilian earthworks contractors who joined in demolishing terrorist infrastructure across the entire sector,” says Col. I.

Positions made of scraps

I meet reservist officer Lt. Col. S. of the 146th division, responsible for the western sector from Rosh Hanikra to Shtula, by Kibbutz Hanita’s perimeter fence. “You should have seen what the wadi here looked like a year back,” he says pointing at the wadi across the border. “It was one hell of a forest and we were working at crazy inclines to remove all the thicket to ensure no one could infiltrate without us spotting them.”

Engineering troops cleared 200 meters to a kilometer from the border. “Take Maroun El Ras, overlooking Avivim: We completely cleared the buildings at the highest spots and took down anything capable of firing at the community. We obviously cleared the whole extensive underground infrastructure that we found in the village an on its slopes.”

The 146th battalion’s engineering personnel cleared a sum total of 9.5 km of tough terrain. “We stretched our engineering capabilities to the limit while, at the same time, supporting the ground operation troops, providing them with engineering jobs deep inside Lebanon,” says Lt. Col. S. “We gave all we could including handheld electric saws in spots the D9s couldn’t reach and machetes to clear paths for the excavators.”

Without taking his eyes off the striking wadi, bare of trees and heavy bushes, he says, “When we found underground bunkers, command centers, rooms for terrorists, observation and firing positions etc., it was a fortified thicket. Now, looking at this area, you can see that the enemy can’t position itself or hide there anymore."

Lt. Col. S. describes the terrorist infrastructure Hezbollah had prepared for its incursion into Israel which Israeli soldiers found in the summer of 2006 beneath the primitive “nature reserves”. “Here, we saw how Hezbollah was preparing to reach the border fence. You’re walking along, and suddenly you feel something unsteady.

You clear the undergrowth, pick up a net, and underneath there’s a wooden panel, and inside there’s a dug-out outpost with complete combat equipment inside a barrel. Under the cover of darkness or fog, all the Redwan forces had to do was take the barrel out, get dressed, pull out the iron frame hidden nearby in the ground, attach the explosive devices, attach that to the wall or fence, and detonate it.

They would then charge ahead with hundreds more militants awaiting orders. Unhindered by UN “peacekeeping” forces, Hezbollah operatives also dug terrorist infrastructure next to UNIFIL outposts.

"When we found underground bunkers, command centers, rooms for terrorists, observation and firing positions etc., it was a fortified thicket."

Each evening, Lt. Col. S. and his personnel would sit down to approve the following day’s sabotage operations. Their need for landmines and explosive materials was met with limited allocations due to immense operational needs in both the north and south.

They came up with creative solutions. It may mean driving to the southern part of the Golan Heights and, cautiously, gathering live anti-tank mines, loading them onto trucks and taking them directly to Hezbollah tunnels and infrastructure. “The minimum we needed to blow up the infrastructure was eight tons and we only had four. We would do everything to ensure we had eight tons,” he says with a smile.

Lt. Col. S. was among the first soldiers to go into the tunnel dug near Moshav Zarit, the only cross-border tunnel structure the IDF found in the north during the war. This tunnel was not yet completed or operational. For months, however, intelligence units and infantry troops had been, “holding,” it, waiting for the order to clear and destroy it.

“So that Hezbollah couldn’t remain there, before approaching the tunnels and underground installations, for which we had extensive intelligence, we destroyed nearby generators, solar panels, ventilation systems and cameras Hezbollah had installed for observation and surveillance purposes.

Lt. Col. S. lives on Kibbutz Dafna in the Upper Galilee and his family was evacuated October 2023. Wouldn’t he have rather taken responsibility for the eastern sector to simply protect his own home? S. replies, “I want to create security for the residents here, just like I expect the 91st division engineering officer to do in his sector.”

He bursts out laughing and says, “Don’t worry. The neighboring sector’s engineering officer Lt. Col. G. lives here with his family in the Western Galilee and we each make sure the other’s area is safer.” Most of the contractors and professionals, alongside the army commanders who played a role in the clearing operation, live in the north.

Cutting down the shrubs

Last week, a few days before the withdrawal from southern Lebanon was completed, I went to examine the clearing operation’s results on the other side of the fence. At the Fatima Gate between Israel and Lebanon on the outskirts of Metula, I met the 91st Division’s red-haired engineering officer Lt. Col. G. We set out together, driving through the Kfar Kila and Al-Aadaissah which I had visited several times over the past year.

They looked totally different each time. “Remember how Hezbollah operatives would be standing on the Hammamis Ridge and would irritate the people of Metula with lasers? You can’t get there by vehicle anymore and anyone trying get there on foot to provoke or harm us - we’ll get to him and take him out,” he promises.

Driving along, we pass huge engineering vehicles that had carved into the rock, crushed roads and houses and flattened lookout platforms used by Hezbollah to overlook Metula and its surrounding and harass farmers tending the nearby orchards. “By Tuesday, this road we’re driving along won’t be here anymore. We’ll ensure there’s no Lebanese movement here and that the sector’s sterile,” says Lt. Col. G.

"Everything preventing the IDF from defending the communities along the border, everywhere I’ve been wanting to get to and address for years, has been obliterated in the past year."

We pass by the spectacular, “Palace of Arches,” which once overlooked Metula, Misgav Am and the Hula Valley. For years, I had seen it from the Israeli side, and now I find myself at the foot of its ruins. The 91st division’s “Barimo Team,” headed by 67-year-old Col. (res.) Avi Cohen (Barimo), is pushing aside the rubble with excavators so as to deepen the buffer zone.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Along the wall surrounding Metula, engineering vehicles are dragging massive piles of barbed wire, laying it into the ground, as yet one more brick to reinforce the sector’s defense.

At our next stop, on the Lebanese ridge overlooking Kibbutz Misgav Am and above the Lebanese village of Al-Aadaissah, just meters from the border fence, we set out walking through steep valley following the sound of a mechanical saw. We walk very carefully, not just because the slopes are steep, but also to avoid tripping over communication cables Hezbollah had laid between their dug-in combat positions, which are very hard to spot.

The reservist "Dvorah" commando unit, made up of Galilee residents, was set up to provide immediate response to any Redwan Force incursion, is clearing the thicket deeper into Lebanon using handheld gas-powered saws and cutting down the most obstinate trees. As part of their work, they have found shafts for accommodation, firing and observation positions, and even explosive devices and a rocket launcher aimed at Misgav Am.

6 View gallery

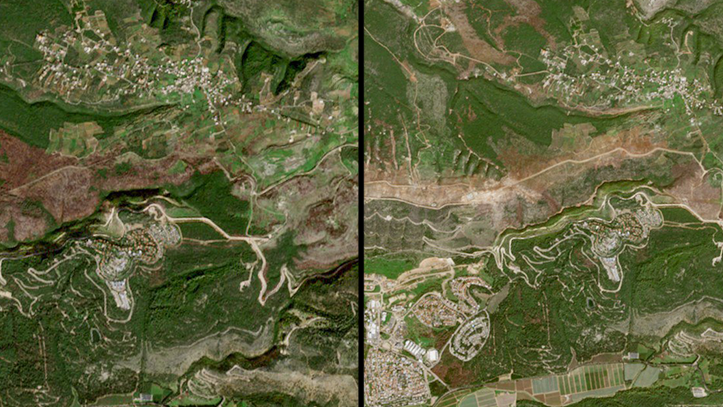

Aerial view of communitie near the border after and before the clearing

(Photo: Ben Zion Mecklass)

“On October 7, we were up there on the mountain, waiting for the Redwan Force,” says Maj. I. pointing at the kibbutz overlooking us. “For months, Hezbollah operatives were wondering around here feely launching Burkan rockets and missiles. In the village below us, the Egoz reconnaissance unit was engaged in a fierce battle.”

Dvorah soldiers, all locals, mostly from evacuated communities, nicknamed this manual engineering operation, “Excessive Pruning”. “It’s very tough work, but we know how important it is. This sector can’t go back to being a combat zone,” say Major I.

He intends returning home with his family next week and is sure it's now safe here: “The situation now is the best it’s ever been. The most important question is how we keep it this way. The work done here is very impressive, and we have to ensure there’s a real buffer zone here so that Hezbollah never returns.”

Last week however, to the dismay of northern residents, Hezbollah operatives returned to what were their homes, and Lebanese engineering vehicles immediately started clearing the rubble so as to rebuild them. Hezbollah flags, are once again visible among the ruins, and Lebanese civilians are try approaching the fence on a daily basis.

Municipality leaders have called out the government for not insisting that the enemy will never return.

Meanwhile, without officially declaring it, the IDF is partially implementing demands of border-adjacent communities to create a security (perimeter) zone in which the enemy cannot move.

This rather narrow strip does not meet the expectation that all the front-line village remain in ruins as a political price Israel should exact for its long-term security. The IDF, however, is committed to stopping or killing any enemy trying to approach the fence by means of various security mechanisms positioned along the 120-kilometer border.

“At the end of the day, the clearing operation is yet one more, highly significant, step meant to provide the residents with tangible and visible security,” says Lt. Col. G. “IDF troops are positioned in front of, rather than behind, the communities and we’re building layer upon layer so that residents of Metula can return to sleep in their own homes.”

“I know the breakdown of trust with the civilians here is complex and replete with fears and concerns,” says Lt. Col. G. “I believe we can bridge this, not by declarations about restoring a ‘sense of security’ but rather, by action demonstrating the security we’ve established here.

"Everything preventing the IDF from defending the communities along the border, everywhere I’ve been wanting to get to and address for years, has been obliterated in the past year. This new security zone means we can improve our control and lethal mobility capabilities in the area. This is in addition to five new outposts set up at strategic security points along the border.”

Only the beginning

That said, IDF officials are well aware that actions taken along the border are not enough to restore trust. This will rather depend on how they act from now on to sustain achievements both along the border sector, and beyond, deeper into Lebanon. “I hope that our message about red lines has also been received on the other side. It would be unwise for them to rebuild their homes on the wall because they’ll be destroyed,” said a defense official this week.

Northern Command engineering forces will now also be tasked with ensuring that clearing operation’s achievements are maintained at all costs. The army will have to avert “afforestation” efforts in the area, with the understanding no ecological intentions lie being planting anything along the border. “We will have to maintain and preserve the new defense line we’ve cleared east to west, ensuring nothing grows or is built on this ground. As far as we’re concerned, this is a kill zone,” say Northern Command officials.

As residents are called to return home and restore their lives and businesses destroyed by Hezbollah fire, Lt. Col. G. talks of a “new contract” between the military and the civilian population. “A woman from Metula needs to know she can sit safely on the balcony in her home, and see everything the army has done and ‘cleansed’ in the terrorists’ villages across the border.

"I believe that, after the war, our response to any efforts at harming civilian security will be stronger. Residents will have to support us so that we’ll be able to prevent and attack any rehabilitation efforts on the other side. We’ll have to respond with harder blows, even when tested with so much as a tickle. We did this under incessant fire. I’m sure we can do it during routine security operations.”

Married father of three small children Lt. Col. G. lives in a Druze village near Carmiel he’s hardly been home since the start of the war. He’s one of 12 siblings. Four of his six brothers are engineering soldiers like himself, and two are serving in the security forces.

His grandfather was killed in action in 1967, for which he was awarded a Medal of Distinguished Service. His father spent his life serving in the police and died of a heart attack. His younger brother G., a reservist officer, was killed by an anti-tank missile during a battle in Rafah six months ago. Of his late brother, Lt. Col. G. sadly says, “My brother was very happy to be taking part in the war defending the state. He'd always say, ‘If we don’t do it, no one will do it for us.”

Immediately following the three days mourning for his brother, he returned to southern Lebanon to command the sector’s engineering efforts. Lt. Col. G. was wounded himself a few months later by a tunnel collapsing. After surgery on his arm, and with metal plates and screws in his arm, he wasn’t waiting for full recovery, but rather got back into the field and to the task of restoring security to the residents of the north.

“The blood of thousands of soldiers who fell here and in the south wasn’t spilled in vain,” says Lt. Col. G. We won’t stop for as long as we’re needed here. I won’t be going anywhere, whatever price we pay at home. If we achieve calm for our children, and in 20 years’ time, they won’t have to fight anymore, it will have been worth the price.”