Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

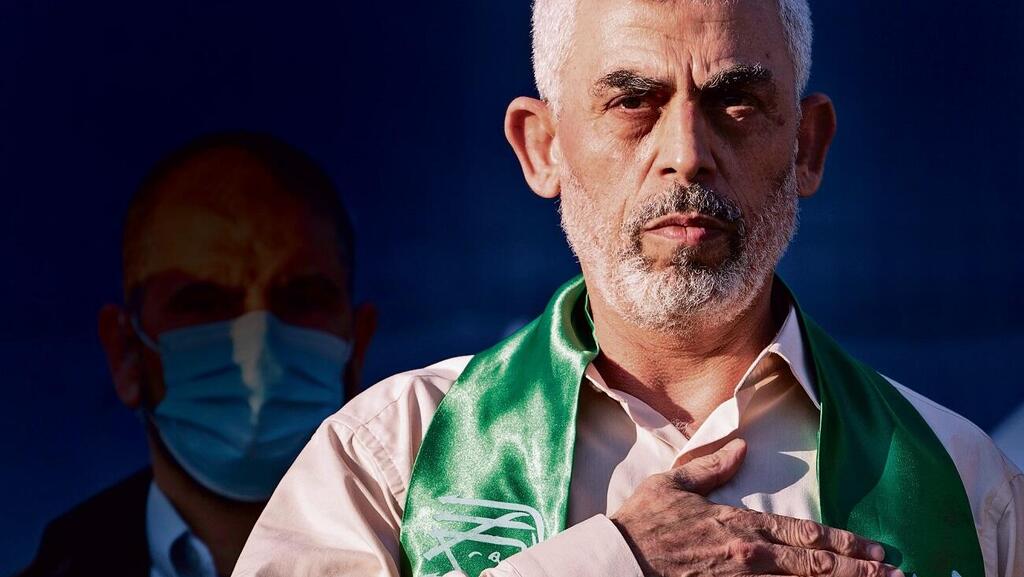

As it currently stands, the Egyptian proposal for a hostage deal and a cease-fire depends on the response of one man: Yahya Sinwar, Hamas’ leader in the Gaza Strip. The signals coming from Hamas’ leadership aren’t positive, despite statements made by senior Egyptian officials to the Arab media. Cairo may be trying to generate some sort of optimism, but the situation seems somewhat different, and Sinwar (again) could be the one derailing the deal.

Hamas' recent successes, particularly on the international stage – such as igniting U.S. campuses and to some extent the world, along with harsh statements from the U.S. government against Netanyahu – have boosted Sinwar's arrogance and confidence, which were already high. Sinwar feels Israel is weaker than ever, both domestically and internationally.

Hamas' main demand so far has been a complete cease-fire. The Egyptian proposal doesn’t include such a stipulation, but it does pave the way for a complete stop to the fighting in the future. The Egyptian proposal says that if the release of the first 33 hostages proceeds smoothly, more of them will be released in the future in exchange for extending the cease-fire and, of course, the release of Palestinian prisoners. Thus, the pause in fighting will transition from temporary to somewhat permanent.

On the other hand, this will allow Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to hold back the claims of his right-wing voters, who do not agree to stop the war but only to a temporary cease-fire. It must be said that after months in which Qatari mediators led the talks between Hamas and Israel, this time Egypt and its general intelligence personnel are the ones leading the mediation efforts.

Some of those involved in the talks are senior officials who are well acquainted with the task at hand: they were involved in brokering the Gilad Shalit deal in 2011, the deal in which Netanyahu's government released Yahya Sinwar from prison along with 1,026 other Palestinian prisoners in exchange for kidnapped soldier Shalit's release.

If Sinwar says no to the Egyptian proposal, he could spare Netanyahu a significant political headache, especially in light of threats from Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who threatened the prime minister that "if you cancel the directive to move into Rafah, your government won’t have the right to exist."

Indeed, the implication of progressing toward a deal with Hamas is, of course, the calling off of the operation in Rafah. If Sinwar agrees, and Netanyahu succumbs to the desires of Smotrich and his ilk in postponing the deal, then Benny Gantz and Gadi Eisenkot are expected to leave the emergency government, and this may also lead to a resurgence of public protest against Netanyahu to a greater extent.

Netanyahu finds himself in a trap and has refrained from doing anything for far too long. This has been going on for far more than a few days or weeks.

It's been several months now that Netanyahu and the Israeli government have effectively avoided taking any real action, any move that would lead to something, be it a formula for military victory in Gaza or a deal for the release of the hostages.

The war came to a halt somewhere around January, only someone forgot to put a notice for the public. There haven’t been any substantial ground operations since the maneuvering into Khan Younis that began in December 2023.

Since then, Netanyahu has been waving the word Rafah around, perhaps to threaten Hamas, but mainly to signal to his supporters that the war continues even though it has effectively ended.

Netanyahu refuses to engage in meaningful discussions on the post-war issue in Gaza, again, because of the political implications for his coalition, and simultaneously doesn’t authorize action in Rafah. In the past few days alone, Israel’s senior officials halted the beginning of the operation in Rafah, and once again Israel is perceived, especially by its enemies, as hesitant and weak, particularly in the eyes of Sinwar and his colleagues leading Hamas.

American pressure is taking its toll regarding Rafah, and Netanyahu hesitates. However, Sinwar's rejection of the Egyptian proposal will likely force Netanyahu to do what he doesn't really want to do – give the IDF the green light to act in Rafah.

The problem is that Netanyahu already understands that even an operation in Rafah won’t change things. It may be a sleight of hand that’s good enough for his supporters, but nothing will change after Rafah – we’ll have to deal with a resurgent Hamas in Khan Younis and the northern Gaza Strip.

And those hostages who were likely transferred to Rafah in December out of concern that the IDF would act on Khan Younis, have probably been moved to new hiding places, which aren’t in Rafah.

And if I should use the words of Thomas Friedman, the New York Times columnist who wrote an article a few days ago explaining that Netanyahu must choose between Rafah and Riyadh, while hinting at the possibility of a normalization agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia should a cease-fire come to pass - then Israel’s prime minister has chosen the third option against Hamas in recent weeks: to do nothing. Neither the stick nor the carrot. Only hoping that his government will survive.