Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

On the Kiddush tables at the Portuguese Synagogue (Esnoga) in Amsterdam every Shabbat morning were plates of herring, salmon, tuna and various pastries. When one member of the small community, a Dutchman of course, saw us focusing on eating herring, he wondered, "You like herring? Israelis and herring?" We responded, "There's no Shabbat without herring on our table." He then added humorously, "But herring like ours can’t be found anywhere. When the prayer ends, some of us bend under the synagogue floor and pull fish straight from the water to the table."

7 View gallery

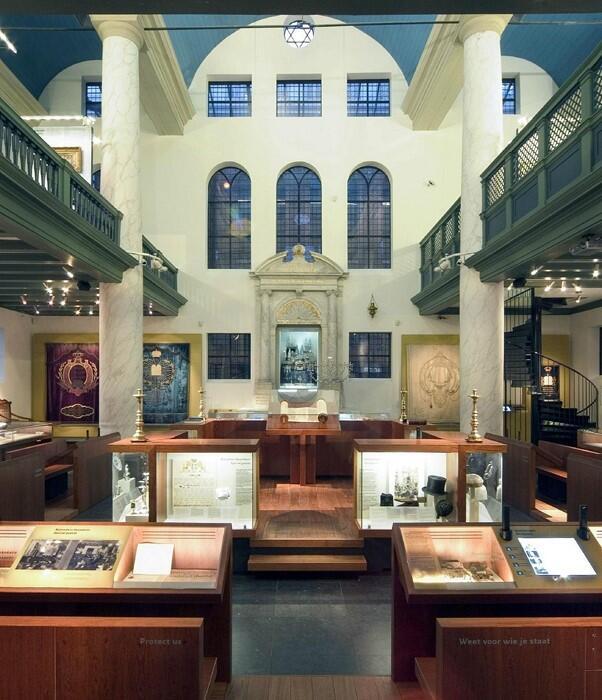

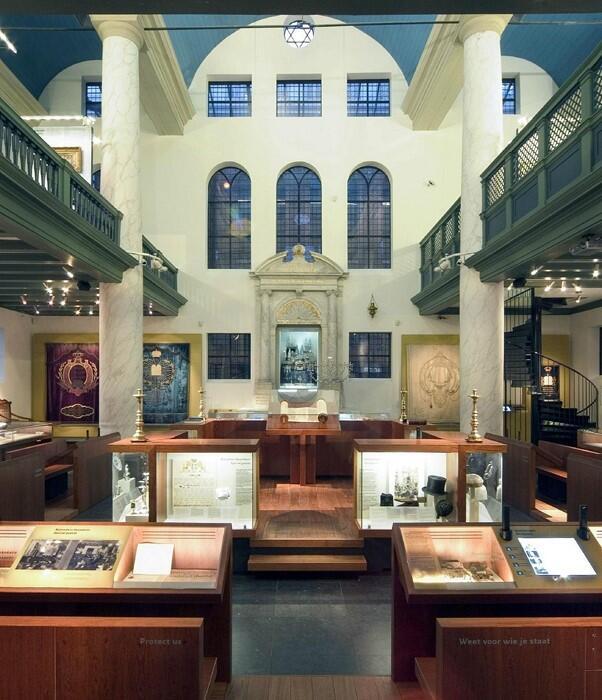

The Portuguese Synagogue (Esnoga) in Amsterdam

(Photo: Courtesy of the Jewish Museuem, Amsterdam)

This, of course, is a charming story, but it contains two important elements: the centrality of herring in the diet of the Dutch in general and Jews in particular, and the fact that the Portuguese Synagogue, inaugurated in 1675, stands on water. This led to thoughts of Emuna Alon's beautiful book House on Endless Waters, which tells the fate of Dutch Jewry during the Holocaust.

To many, the image of the Netherlands during World War II is entirely different and more favorable compared to Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Vichy France and other countries. However, this image is completely distorted. Of the approximately 140,000 Jews in the Netherlands on the eve of the Holocaust, more than 107,000, or about 75% of the Jewish community, perished during the darkest days.

The number of Righteous Among the Nations in the Netherlands is indeed exceptional, with 5,982 people recognized for protecting and saving Jews—an act worthy of high praise. However, this does not absolve their compatriots who betrayed thousands of Jews to the Nazi regime.

Noteworthy is the village of Nieuwlande in northeastern Netherlands, where all 117 residents were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. Emuna Alon wrote in her book, "One cannot blame the Dutch for what happened, because the Dutch are simply disciplined by nature, accustomed to maintaining law and order and doing what they are told" (p. 63).

Standing out in a city of museums

How can a small community museum with limited resources stand out and attract visitors in a city that boasts some of the world's largest, most important and beautiful museums? Moreover, the museum most associated with the Jewish story is the Anne Frank House, which draws thousands of visitors daily.

7 View gallery

The Jewish Museum in Amsterdam within the Former Great Synagogue Building

(Photo: Courtesy of the Jewish Museuem, Amsterdam)

We decided to forgo another visit to the Anne Frank House, which we had already visited multiple times, and instead explore the newly renovated Jewish Museum in Amsterdam. Its energetic director, Prof. Emile Schrijver, has made significant changes to the exhibits, both in terms of the items displayed and the overall scope.

While we did not skip the Rijksmuseum, thanks in large part to its 17th-century Rembrandt paintings and 19th-century Impressionist art, nor the nearby Van Gogh Museum, inspired by whose works we once traveled through southern France, our primary goal was the Jewish Museum. Our friend Bill Gross, the renowned Judaica collector, assured us we would be amazed by what we saw.

Bill delivered on his promise. Together with Prof. Schrijver, who constantly surprises us with new information, we toured the extensive complex comprised of four Ashkenazi synagogues in Amsterdam—the Great Synagogue, the New Synagogue, the Third Synagogue and Obben—built in the 17th and 18th centuries. These synagogues, located in the Jewish Quarter, were left empty of worshippers after the Holocaust. The adaptation of the four synagogues into a museum took many years, and today they are filled daily with hundreds of visitors eager to learn about Dutch Jewry and the unique heritage of the community.

The impressive museum uses all available technological and museological means to captivate visitors. From the museum's collection of 11,000 items, several hundred Judaica artifacts were selected—silver and gold items, manuscripts, paintings, religious objects such as an Ark, shofar, menorahs, household items representing daily life such as Kiddush cups, challah covers, Seder plates and more—displayed in a visually appealing manner that overwhelms the visitor with their richness and color.

The manuscript collection offers insight into the unique traditions of Amsterdam's Jewish community, a blend of customs from the Iberian Peninsula brought by the expelled Jews of Spain and Portugal, and Ashkenazi traditions from Western Europe.

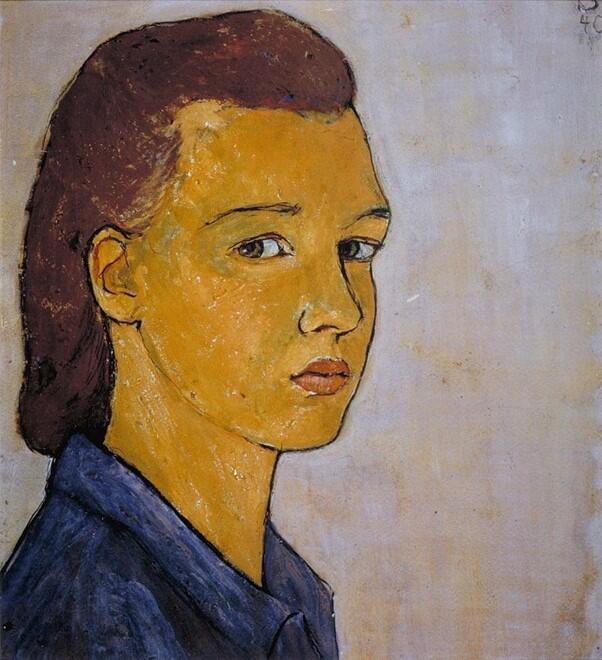

Charlotte Salomon, a Jewish-German artist who perished in the Holocaust, is a well-known name in Holocaust history and art history. She created 1,300 paintings in one year, documenting her family in a dramatic style. After the Holocaust, her parents relocated to the Netherlands, and in 2006, all her works were donated to the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam. "We have a unique and very special treasure," says Prof. Schrijver.

When I asked about visitors to the Jewish Museum in a city with many museums, Schrijver mentioned Jewish visitors from around the world, but even more so non-Jewish visitors—thousands of Dutch schoolchildren visit both the Jewish Museum and its additional part, the Holocaust Museum, about a ten-minute walk away. In both parts, they learn about Judaism in general and Holocaust history in particular within an organized classroom setting.

And what about Israelis? "Unfortunately, among the thousands, maybe tens of thousands, of Israelis who visit Amsterdam every year, only a few visit us," says Schrijver. Our recommendation: Don't miss it. Dutch Jewry welcomes everyone, and in the Jewish Museum, you'll discover a world of beauty you never knew existed.

The world's oldest Jewish library

Amsterdam's Jewish Quarter is a popular destination, drawing hundreds, sometimes thousands, of visitors daily. By nine in the morning, at least ten tour groups, mostly non-Jews, were already wandering around the quarter centered on Waterlooplein, just minutes from Dam Square, waiting to see the area's treasures.

Even before the Holocaust, the synagogue building adjacent to the Jewish Museum was designated a national heritage site, and it still has no electric lighting, just as it did 350 years ago. On the rare nights when prayers are held there, they take place by the light of hundreds of hanging or fixed candles.

The synagogue is meticulously maintained; everything is spotless, the silver and gold artifacts are polished and the Ark looks as if it was handcrafted recently. The floor remains as it originally was—sand over parquet—to maintain silence, absorb dust and moisture and most importantly, as a reminder of the Israelites' journey through the desert.

The synagogue itself, where 30-40 Jews pray on Shabbat, is built on wooden stilts standing in water, and maintenance boats can navigate underneath it. Surrounding the synagogue is a large courtyard enclosed by low buildings forming a kind of wall. These buildings include the winter synagogue (with lighting and heating), offices, the community archive, the Etz Chaim Library, a mikveh and a tahara house.

The Etz Chaim Library, a must-visit, was founded in 1639 and is renowned in Jewish literary history. It moved to its current location in 1675 and is recognized as the oldest functioning Jewish library in the world. Since 2013, it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Heidi Warncke, the curator and director, speaks Hebrew and is deeply knowledgeable about Jewish life and tradition. Her expertise in Jewish literature is impressive, and she holds a Ph.D. in Jewish Studies.

The beautiful library houses 30,000 books, all related to Judaism, including hundreds of historically significant manuscripts. The eye cannot tire of seeing and reading the numerous books and manuscripts that Warncke lays out, many of which you may have only heard of or seen in photographs.

Here are the originals, centuries old. The extensive and fascinating collection covers all the walls, creating an atmosphere of silence and contemplation; a magical world for thought, reading and writing on all aspects of Jewish law, history, philosophy and science.

7 View gallery

Exhibition of Charlotte Salomon's Paintings at the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam

(Photo: Dorit Rappel)

The entire Jewish Museum complex and the Portuguese Synagogue are worth a full day's visit. Time with our hosts is limited, so we move quickly from Heidi to Miriam Knutter, who takes us to the treasures of the Portuguese Synagogue, gathered in the room that once served as the rabbi's study, the adjacent rooms and the rooms below. Miriam, born in the Netherlands, lived in Israel for several years, is married to an Israeli and speaks fluent Hebrew.

"At home, we speak Hebrew, and our children are fluent in Hebrew," she says. Emphasizing Hebrew highlights that the museum and its staff are very friendly to Israeli visitors. A significant portion of the staff speaks Hebrew, making the visit more pleasant and enjoyable.

Remembering, not whitewashing

The name of architect Daniel Libeskind is almost automatically associated with Holocaust memorialization and the preservation of Jewish memory. Despite his numerous unique works, the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the large memorial in Amsterdam are undoubtedly two of his most significant projects in this field. The story behind the Amsterdam memorial is worth knowing.

Sammy Herman, a Jew born in England who moved with his parents to the Netherlands in his youth, guides us through the Holocaust section. Sammy, who makes his living translating books from Dutch to English, lives near the Portuguese Synagogue and, as an observant Jew, he walks to the synagogue every Shabbat to ensure there is a quorum of worshippers. Sammy’s Hebrew is also quite good.

The initiative to memorialize Dutch Jewry began in 1950. Five years after the Holocaust, a monument was erected to commemorate the approximately 100,000 Dutch Jews who perished. In those days, the prevailing belief was that the Dutch did everything possible to save Jews from certain death, and thus the monument was named "Gratitude."

Over the years, as research expanded and more documents and testimonies were discovered, it became clear that the rosy picture painted by the first monument was as dark as that recognized in other European countries. Against this backdrop, a new initiative emerged to build a more accurate memorial, which was erected on a main thoroughfare in the city, just a five-minute walk from the Jewish Museum and the synagogue.

The planning was entrusted to architect Daniel Libeskind, who designed on an area the size of a basketball court a series of walls that, when viewed from above, form the word "Remember." The walls were built from 102,000 silicate bricks, each inscribed with the first name of one of the Dutch Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

It seems almost necessary to proceed from this special monument to the new, large Holocaust Museum, which opened only about three months ago with the presence of King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands, Israeli President Isaac Herzog, the chancellor of Austria and many other dignitaries, most notably the families of Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

Every Holocaust memorial museum offers a unique approach chosen by the architect and curators to depict the destruction and cruelty of the Nazi regime. At Amsterdam's Holocaust Museum, I found particular interest in the personal items donated by community members for display—spoons from their parents' home, plates, religious artifacts, clothing—each item and exhibit bringing visitors closer to the Jewish Dutch families that were murdered.

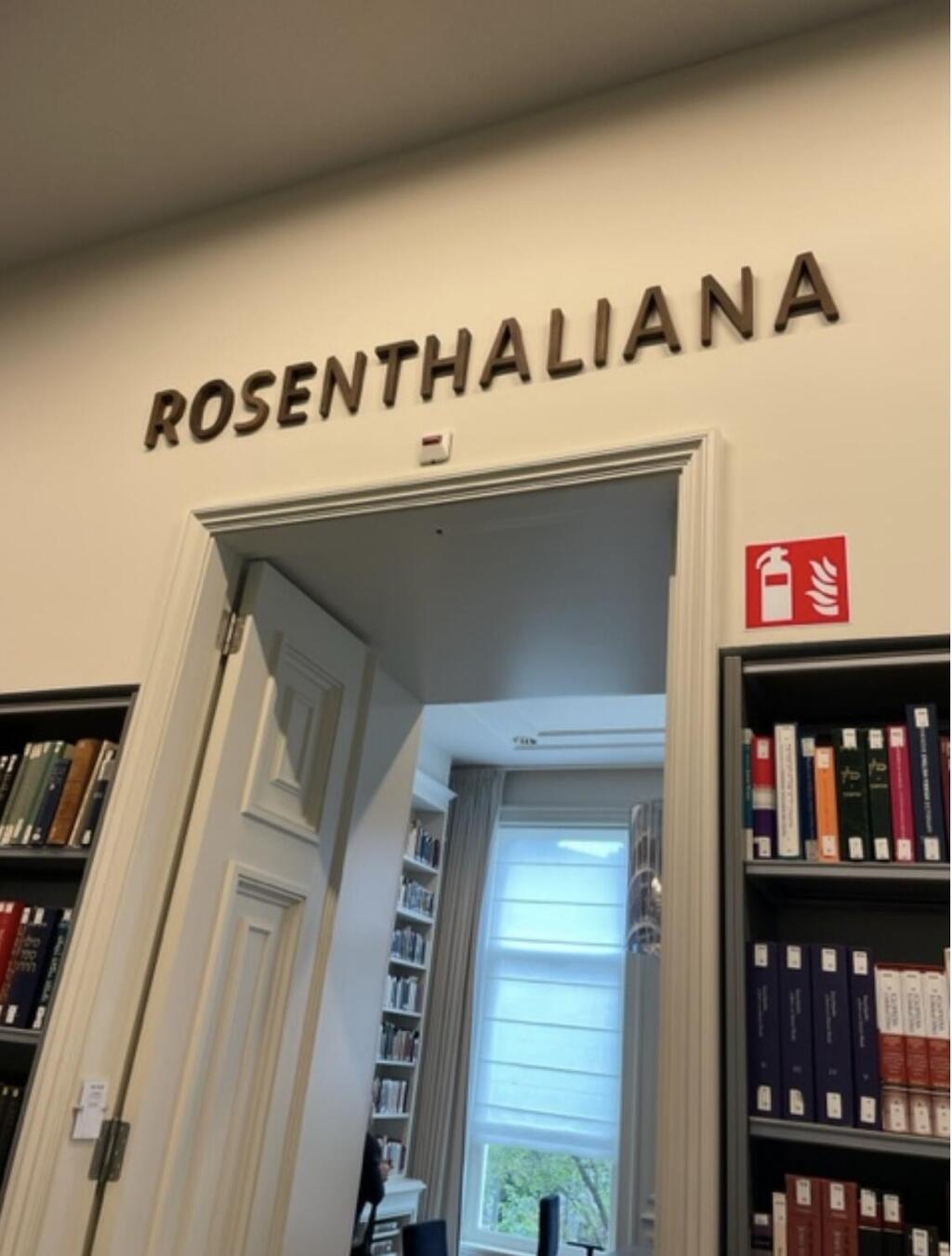

Written treasures

There is hardly a devoted Hebrew book lover who isn't familiar with the Rosenthaliana Library, the largest Jewish library in continental Europe outside of England, now part of the University of Amsterdam. The university has long maintained a program in Jewish Studies.

My personal memories led me to a large building on the bank of one of Amsterdam’s canals, a place I had visited before. However, in this case, the Hebrew saying "Change your place, change your luck" applies—the university relocated the library, which houses over 120,000 books, 1,000 manuscripts, ephemera (one-day printed materials), incunabula (books printed before 1500) and various archives, to a new building in the heart of the city, just a few minutes' walk from most of Amsterdam's main attractions.

The library, founded in 1880, began with the personal collection of Eliezer (Lazer) Rosenthal (1794-1868). Rosenthal's heirs wanted to donate the entire collection to Germany, offering it to Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. After the German leader showed no interest and refused to accept the library, they offered it to the Netherlands, which gladly accepted it. Since the national library is part of the university, it was transferred to the University of Amsterdam.

In the library's reading room, we are greeted by the curator and director, Dr. Rachel Boertjens. She was born in Jaffa, the daughter of a former minister at Immanuel Church. She is also fluent in Hebrew. She shows us some of the library's "big stars"—mainly manuscripts and hand-illustrated books, each copy unique.

The old library space was small, cramped and operated within a few closed rooms. The new location is more spacious, and the procedures for examining books are stricter. Rachel busily brings out interesting and special books, and together we explore various editions of the Amsterdam Haggadah from 1695, the Esslingen Machzor from the 11th century, Hebrew books printed over the years in Amsterdam, the Jacob de Haan archive and other great and wondrous surprises.

Amsterdam is a city of tourists and tourism. Thanks in large part to Prof. Schrijver, who has positively transformed the meticulously preserved Jewish sites overseen by the Dutch government, the tour stimulates an appetite to stay longer, delve into manuscripts and rare books, get to know the various museums better, and discover that there is much more to see beyond the sites that attract millions of tourists.