Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

I am fortunate today to hold the position once held by Max Nordau. Dr. Nordau was Herzl's deputy when, at the First Zionist Congress, the latter founded the World Zionist Organization. Today, I serve in this role of Vice Chairman. However, there's no comparison between Nordau and I. Nordau was an immense figure; I am a mere grasshopper in his shadow. Nevertheless, I enjoy reading the articles and speeches of a man who occupied such a central role in the Zionist Movement, who was such a gifted orator, a magnificent polemicist, and who was privileged to have served alongside Herzl.

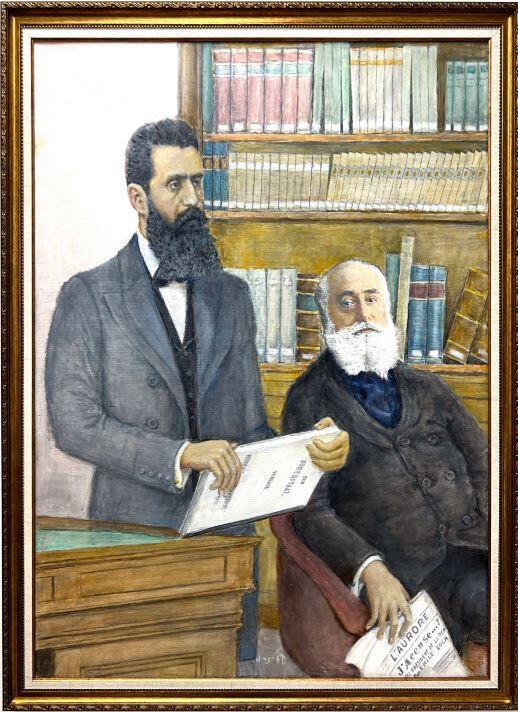

Nordau, a physician, was an educated man with broad both knowledge and physical dimensions. The proud owner of a white beard that he meticulously and somewhat strangely combed to the sides, distinguishing him from most of the people around him.

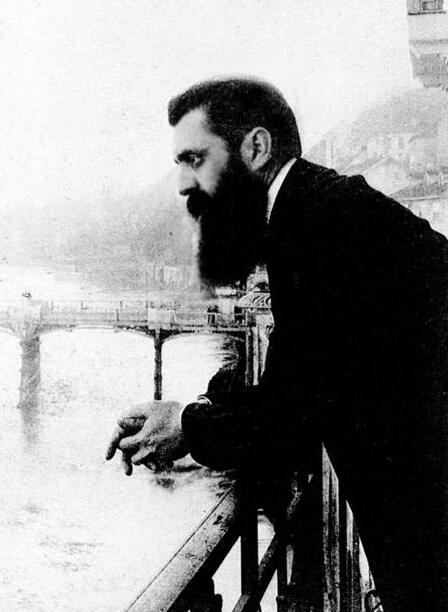

In contrast, Herzl, who held a Ph.D in law, was tall and slim. His beard was black, meticulously groomed. His clothes were elegant and fashionable, his bearing refined. They differed in appearance, in temperament, in age (Nordau was more than a decade older than Herzl), and in public standing. Nordau was much more well-known than Herzl when the First Congress convened. The very participation of the esteemed author and physician in the Zionist Movement created a sensation. As we will see below, Herzl may have even alluded in his diary to the fact that Nordau himself wished to stand at the head of the Zionist Movement, an aspiration that remained unfulfilled.

The relationship between the two was so unique and delicate that I wish to dedicate this article marking 120 years since Herzl's death, to the man who stood at his side.

Nordau was very serious as well as aware of his own stature. In this sense, he actually resembled Herzl. Neither was petty or especially modest. The hierarchy between them should have seemingly been obvious. The publicity, the status, the age. However, something happened to Nordau at that first Congress that caused him not only to overcome his inclination but, also, to understand that he had the privilege of standing alongside a unique figure in Herzl. He grasped in real-time that he was less talented than his younger colleague and, henceforth, for the sake of the Zionist cause, he did everything in his power to assist the leader of the Zionist Movement to realize his vision. Let us look at for a moment at a famous incident prior to the opening of the First Congress.

It's well-known that Herzl the journalist found himself thrust into that profession somewhat by chance. He would have been a happy man had he succeeded in making a living and gaining acclaim as a playwright. His soul was bound to theater, which he lived, breathed, and understood. His dream was to become the most famous playwright in Europe. Indeed, Herzl wrote several dozen plays, some of which were even performed on stage. Fortunately for us, none of these was a resounding success. The world of theater's loss was our gain. However, Herzl's dramatic talent did not vanish when he became a Zionist.

He meticulously planned every detail of the First Congress in Basel. He knew that his book 'The State of the Jews', written feverishly and published a year before the Congress, was not itself sufficient. That for an abstract idea to allure and captivate audiences, it must be properly presented. Theater has magic – so let us take the Zionist idea and make it magic too. A Jewish state? Let's simulate a parliament with all its rules and etiquette.

Immediately upon arrival in Basel, Herzl canceled the hall originally reserved for the Congress and chose another grander, more fitting location. For the next three days, he occupied himself with its design. He thought of every detail – how the stage would look, how the flag should be hung, where the audience would sit, where the Congress's leaders would assemble, and where the speakers would stand. The content of the Congress naturally received the same attention to detail. The agenda, published in advance like that of a parliament, determined who would speak when. Herzl also knew exactly about what.

The opening session was set for 10:00 on Sunday, August 29, 1897. The elegant invitation also stipulated the dress code: a frock (the German term for a tuxedo), a white bow tie, and a top hat. Nordau apparently considered this excessive. I can imagine Herzl standing at the entrance to the hall at 9:30, enthusiastically greeting attendees when suddenly his eyes freeze. This is the description in his diary:

"Nordau appeared on the first day dressed in a riding jacket! And he expressed absolutely no desire to return home and dress in a frock coat. I pulled him aside and implored him to do it for my sake. I said: The Zionist Congress is still without substance; it is our responsibility to create it all. But the people must view this Congress as a most noble and festive spectacle. He acceded to my request and I hugged him gratefully. A quarter of an hour later, he returned wearing a frock coat".

The truth is that the following paragraph from Herzl's diary, the one appearing after the above description of the frock coat incident, arouses my suspicion that Herzl was not necessarily surprised by Nordau's wardrobe protest. He certainly knew that Nordau bore a grudge against him. But did these two Hungarians (both Herzl and Nordau were from Budapest) ever refer explicitly to the tension that existed between them? It doesn't seem so.

Herzl continues: "I took it upon myself to ensure that Nordau forgets during those three days that he was of secondary standing at the Congress, a fact which pained him visibly. I emphasized at every opportunity that I am only the chairman of the Congress by my knowledge of the people and issues, purely technical knowledge, and that had it been otherwise, he would have been worthy of the role of chairman in my stead. My words improved his disposition somewhat. Moreover, his speech fortunately received greater acclaim than my purely diplomatic address and I proclaimed to anyone who would listen that Nordau's speech at the Congress outshone all the others!"

It would seem however that the resounding success of the First Congress - Herzl's charisma, the impeccable way he conducted the discussions, and the leadership skills he demonstrated and which aroused both wonder and solidarity - all had their impact. Herzl's position was set and, henceforth, it would be clear that he was the figure on whom all eyes would be focused. Nordau had no further need to suppress his affront or envy. It simply evaporated as Herzl's natural leadership conquered him, too. He sensed, like many, that he was almost gazing upon a wonder. A unique personality is seemingly born for this specific moment in the life of people. With the feeling that the role of the people, including Nordau himself, was not merely to vacate the path for him but to pave it.

To what degree did Nordau admire Herzl?

A clear, amazingly creative example can be found in a critical article that Nordau published about Ahad Ha'Am when the latter dared to issue a stinging yet legitimate critique of the novel 'Altneuland' published by Herzl in 1902.

Although the majority of those attending the First Zionist Congress in Basel enjoyed the gathering, this was not a universal sentiment. Ahad Ha'Am, the literary pseudonym of Asher Zvi Ginsberg - the founder of cultural Zionism, was not so dazzled. In fact, he was not even among its 208 delegates. He arrived in Basel as a "journalist" on behalf of the 'HaShiloach' journal which he edited, and only then, after he insisted on receiving a personal written invitation from Herzl. He liked nothing he saw in Basel. In his words, he walked around the Congress like a mourner at a wedding. Even before the ideological dispute between these two protagonists, with one attempting to solve the problem of the Jews and the other the problem of Judaism, a quick glance at them both was sufficient to discern how much their meeting was doomed to fail. Ahad Ha'Am was a slight "Galitzianer", a "Yiddisher" in essence but a speaker and writer of exemplary Hebrew, with complete command of the Jewish library.

A gifted essayist, one of the leaders of 'Hibbat Zion' and, as noted – editor of 'HaShiloach'. Herzl was the exact opposite. In appearance, language, and his lack of Jewish education. In his aspirations to turn the world on its head, coupled with the daring to step up and do so. Ahad Ha'Am perceived Herzl's statesmanship as impulsive, megalomaniacal, and insufficiently Jewish. In contrast, Ahad Ha'Am's cultural Judaism seemed to Herzl to be a footnote and not, to his mind, the way to save the Jewish people.

However, as always, not everything revolves around ideology. Until Herzl appeared on the stage of Jewish and Zionist history, Ahad Ha'Am was the soon-to-be crowned leader. He was famous. He exerted a marked influence and led an inspirational trajectory of secular Jewish renewal. He challenged the 'Hibbat Zion' Movement that advocated a practical Zionism of individual immigration to agricultural settlements in the Land of Israel and called to add a spiritual-cultural dimension. His name preceded him by virtue of his essays and literary endeavors. And now he was faced with Herzl, deciding to convene the Congress and conquering the Zionist Movement without a fight.

When Ahad Ha'Am published his lengthy and reasoned critique of 'Altneuland', he did not hold back. Herzl had let his imagination soar in the book. He conceived a utopia: an advanced modern state with trams and an opera house and harmony between cultures and religions. All this aroused Ahad Ha'am's ire. 'Altneuland' contained not a semblance of Judaism. Is that the sum of the aspiration for the Return to Zion?

And he did not only criticize the idea itself but also its harbinger. He targeted Herzl directly: "Indeed, we know of the ideal of political Zionism, as portrayed in the imagination of its primary leader. To remove himself from "national chauvinism" to such an extent as to leave almost no trace of the People's national attributes, its language, its literature, and all its spiritual inclinations. An apish imitation, devoid of any original national quality".

An apish imitation? No one dared to speak to or about Herzl in such a manner, let alone write in this way. Especially in the prestigious 'HaShiloach' journal. Herzl was hurt. Nordau knew well that Herzl would not respond himself. That was not his way. Not in tune with his graces. He took the initiative and published a no less reasoned but more stinging article in the 'Die Welt' newspaper – the outlet of the Zionist Organization. He too did not limit himself to only addressing the idea but also, the man behind it:

"Ahad Ha'Am has one good quality: he writes in nice and flowing Hebrew. That is praiseworthy. It is nevertheless a pity that he has nothing to say in this fine Hebrew. Absolutely nothing. His supposed "studies" are nothing more than word fillings, of which I have no term in my vocabulary to explain their complete insignificance. It is nothing more than a jumble of babbled words, vague and detached from their European polytonic. A chaos of speech parts which we scour in vain for even one clear, well indicated, sophisticated and logical idea that is comprehensible to the reader".

This is what anger, or maybe even fury, looks like and how it is written. Nordau was hurt on Herzl's behalf and wrote an article like a Hassid defending his rabbi. Make no mistake – this is not an article written by a pious fool (God forbid). Nordau's article is well-reasoned. The above quote is but an impassioned morsel from it, but the anger and indignation ooze from every line. An illustration of the degree to which Nordau respected and admired Herzl.

Dr. Yizhar Hess

Dr. Yizhar HessHerzl's death in 1904 dumbfounded the entire Jewish world. Herzl died in the prime of his life at age 44. Nordau, although 11 years his senior, was his comrade, partner, and confidante. His friend's death was a bitter blow to Nordau, not just personally but also because he was among those who instantly understood how much the death of this unique leader could endanger the future of the Zionist Movement.

Nordau was well-read and erudite, and the words he chose to eulogize Herzl are thus beautiful and measured: "Herzl was less of a poet than Heine, less of a speaker than Disraeli, with less imagination than George Elliot, and less of an organizer than Baron Hirsch…but he was the greatest of them all because he had them all".

'HaShiloach', Vol. 10, Book 6, December 1902

'Die Welt', March 13, 1903

- Dr. Yizhar Hess is the Vice Chairman of the World Zionist Organization