Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Last Friday around midnight, observers from the IDF Bashan Division (210) and border security troops stationed in southern Golan Heights were stunned by what they saw: a Syrian officer assembling his troops in a U-shaped formation at the Tel Kudana outpost. The officer then ordered them to abandon the company base, which overlooks Israeli communities like Keshet and Aloni Habashan.

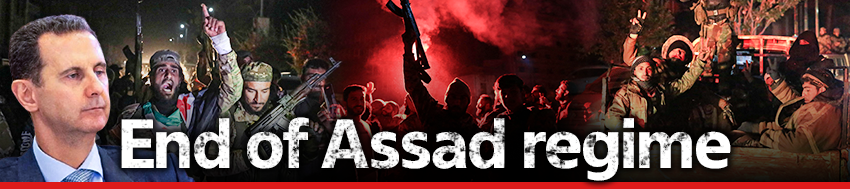

Within ten minutes, the soldiers hastily boarded trucks and fled eastward, leaving behind three Soviet tanks, seven anti-tank missiles and damp trenches. Two days later, 101st Battalion paratroopers captured the outpost—nicknamed the "Syrian Pita"—without firing a single shot. Fifty years of cease-fire agreements dissolved in an instant, without a fight.

After a bumpy half-hour ride in an armored Tiger vehicle along the rugged route from Aloni Habashan to Syrian territory, the shift was clear. Descending through a grove of pine trees, the color of the barrels marking the border changed to red, white and black—the colors of the Syrian flag. We had crossed the border.

The barrel line marks the internationally recognized border between Israel and Syria, which held firm for exactly 50 years under the cease-fire agreement between Hafez Assad's regime and Israel. Now, this border has blurred, nearly disappeared, and could remain so for months or even years.

The IDF's official line is that it is "securing commanding points in the buffer zone along the border," but this buffer zone is sovereign Syrian territory, which until Friday was under the control of Assad's army.

Four battalion combat teams from the Paratroopers, Commando Brigade and the 188th Armored Brigade are operating here in what the IDF calls "forward defense." This contingency plan, long in place in every regional division, has been employed in past wars and operations: to seize key positions on enemy soil near the border during an emergency to preempt and push back potential threats to Israeli civilians.

Hundreds of IDF soldiers now traverse the area in light vehicles like Defender jeeps and pickup trucks, as well as tanks and D9 bulldozers. They are moving through the streets of Quneitra and other Syrian border villages, including Kudana. On Wednesday, Israeli journalists entered these areas for the first time.

The Syrian children born in Israel

It may be hard to believe, but for the Syrian residents here, the situation feels almost natural. “They didn’t greet us with rice (as the residents of southern Lebanon did during Operation Peace for Galilee in 1982), but they were happy we came. They spoke to us openly after years of fearing to do so under the watchful eyes of Assad’s soldiers,” said Lt. Col. (res.) Inon Oriya, deputy commander of the 474th Regional Brigade, who lives in the Golan Heights near Syrian villages.

"A few days ago, an elderly Syrian couple approached me in broad daylight, sharing their joy at Assad’s fall while working their fields," Oriya added. "They want nothing but peace and livelihood and remember the help we provided them during the civil war a decade ago."

Approximately 70,000 Syrians live in the Syrian Golan, with Khan Arnaba, near Quneitra, serving as the regional center.

“The IDF quickly understood the importance of stabilizing the situation proactively this time, learning from past lessons in Gaza and southern Lebanon,” explained a senior commander.

Positive messages were sent to the Syrian regional governor and local village leaders. This dialogue, while not new, was seeded during Operation Good Neighbor, when Israel provided millions of shekels in medical aid to thousands of Syrians treated in Israeli hospitals and, according to foreign reports, supplied them with weapons.

Dozens of Syrian babies born in Israeli hospitals like Ziv Medical Center in Safed or Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya are now eight-year-old children, watching Egoz and Paratrooper soldiers patrol their villages.

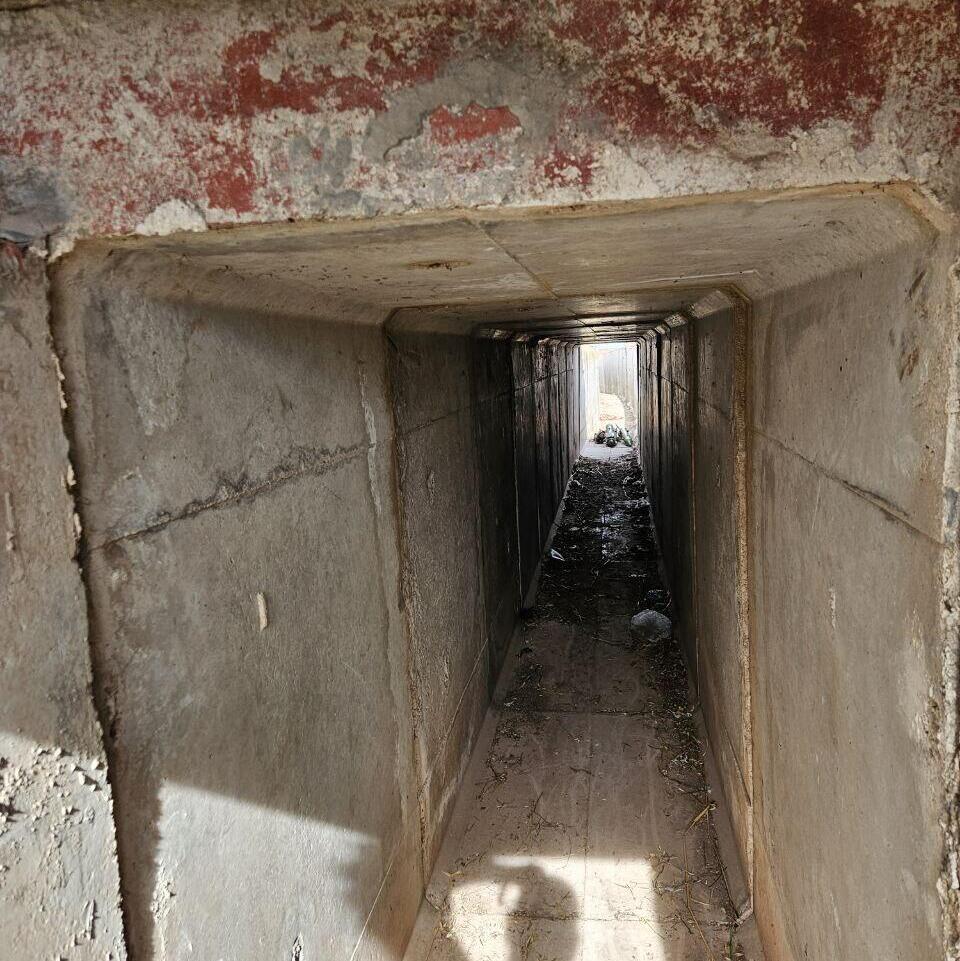

IDF forces plan to remain in the area through winter, preparing for the snowy conditions ahead. Bulldozers are carving new routes, and soldiers have received thermal clothing for their static security duties, including guard posts, patrols and ambushes. Heated, collapsible living quarters have been deployed to outposts alongside noisy generators, replacing the old Syrian bunkers, which soldiers described as unpleasant for sleeping.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

A makeshift guard post, marked with a large sign reading “Gatekeeper,” is manned by three Paratrooper soldiers. One of them, requesting anonymity, cited concerns over global perceptions of IDF operations following the Gaza war. Despite this, morale is high, with optimism evident among the troops.

“This feels different,” said an officer. “For the first time, it seems something good is on the horizon, both for the region’s residents and the Middle East as a whole.” A Druze officer even took advantage of the new reality to send aid to relatives in Syria.

IDF soldiers have been actively establishing control. In the first two days, they intervened when local Syrians, likely backed by armed rebels, were caught looting equipment from an abandoned UNDOF outpost. The soldiers forced the items to be returned to UN peacekeepers, who, while still patrolling in their blue uniforms, are effectively redundant.

"The IDF plans to stay until a legitimate and recognized government is established in Damascus capable of taking responsibility for the Syrian Golan," a commander explained. "We won’t allow another border with terrorists like Gaza or Lebanon. The baton will only be handed over to a structured, state-backed force, even if it takes a year."

Tracking IDF movements

This tumultuous year is once again upending the IDF’s operational plans. Battalions have unexpectedly arrived in the Golan Heights from southern Lebanon, disrupting all projections. Some rear IDF positions on the Israeli side of the border may now need to adjust, adding to the military’s already full plate of challenges.

For now, front-line defense will be handled by regular forces under the command of Brig. Gen. Yair Paley, head of the 210th Regional Division. Paley, a seasoned officer, began his career as a Golani Brigade recruit and later commanded the brigade in ground operations in Gaza.

He is likely the only officer here who trained in capturing "Syrian Pita" outposts—a skill no longer practiced since the early 2000s, when the outbreak of the Second Intifada marked the end of any realistic chance of such operations in Syria.

These outposts, perched on hilltops, earned their nickname due to their pita-like shape. Circular trenches surround the outposts, and within them are fortified living quarters for soldiers. On Wednesday, I walked through these abandoned and damp Syrian trenches. On the wall of one, I saw a torn picture of Bashar Assad, pierced through the forehead by a hanging hook.

At a sniper post extending from the trenches, a paratrooper stood alert, peering through a scope aimed at the terrain. The observation slit he used had been manned by a Syrian soldier just a week earlier. The sniper, a lone soldier from the 101st Battalion, spoke in a heavy American accent: “In recent months, I fought in Gaza and southern Lebanon. This place is entirely different.”

Inside the outpost’s rooms, I found a discarded Syrian gas mask and iron mess kits resembling those used by IDF soldiers in the 1960s. One still contained moldy food, evidence of the Syrian soldiers' hasty retreat last weekend.

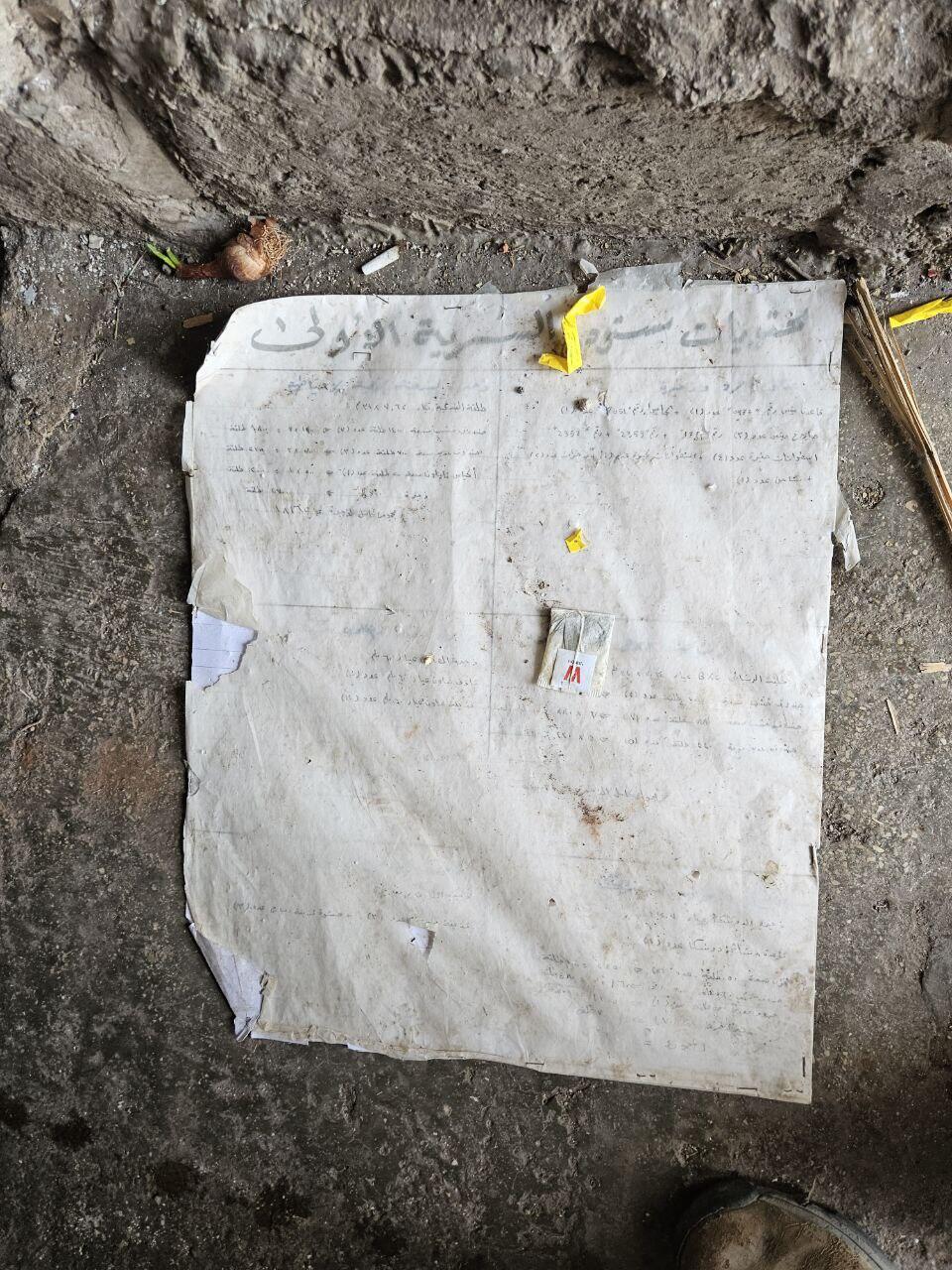

Scattered nearby, among charred ceilings and empty ammunition boxes marked with Cyrillic script, lay dirtied sheets of paper written in Arabic. A quick translation revealed them to be observation logs detailing IDF soldiers and their daily routines across the border—records kept from this vantage point for the past 50 years.