It was one evening in 1977, when he joined his late father, Yosef, who had been invited to give a talk to a group of IDF soldiers. There, surrounded by dozens of young men in uniform that he didn’t know, he heard for the first time of the horrors his had family endured.

Young Dadush was dumbfounded. He saw his beloved father as never before. At first, he listened dutifully, like any other youth paying his respects to the memory of the Holocaust, as one would stand for the siren. He gradually began taking in the astonishing, horrifying details of the story his father was telling. These were his roots.

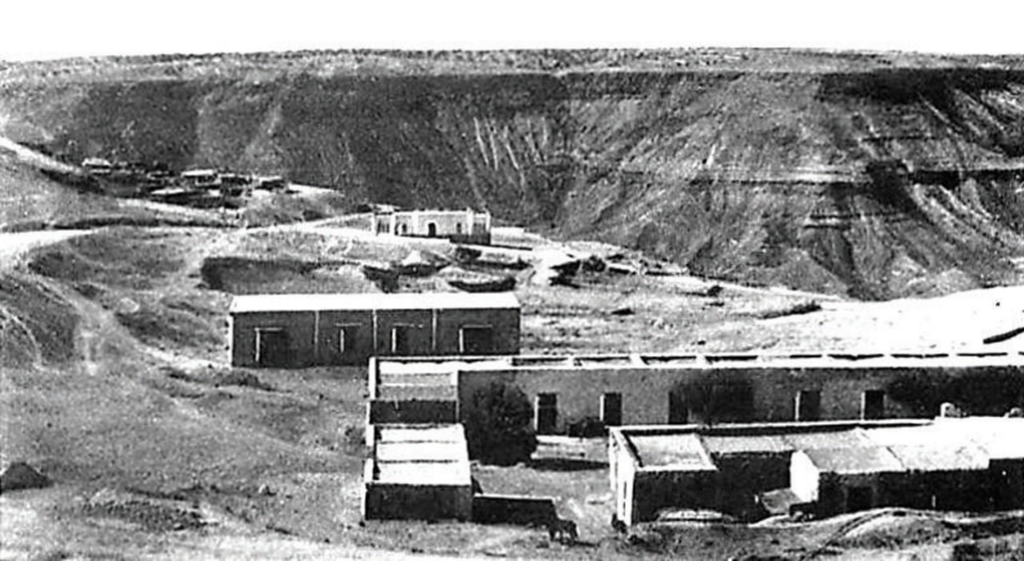

“I knew that my father and mother had been in a camp in Giado, south of Tripoli in Libya, but nothing more than that,” he says today.

“It wasn’t until my father told the story about the babies in that talk that I learned that I’d had an older sister born in the camp. I didn’t know that she had contracted typhus when she was three months old and that when they took her to see the camp doctor, the Nazi injected her with poison and she died within a matter of hours.

"I asked him to explain why I hadn’t known anything until now, why he’d hidden it all from me.”

"I was shaken to the core when my father spoke her name. ‘Ada.’ My body became detached from itself. He couldn’t be talking about us, about our family.“

It's been 45 years since that evening. He clearly remembers the journey home after that talk, and the argument with his father: “I told him that it made no sense, that it wasn’t fair that I should have to hear our story like this. I asked him to explain why I hadn’t known anything until now, why he’d hidden it all from me.”

Yosef was a proud Israeli citizen of 25 years. “He wasn’t fazed. He said ‘We’re now living in the State of Israel, and everything’s fine. It’s just history. These are things that happened to me and your mother before you were born.’ I felt he was protecting me. On the one hand, he wanted to spare us the horrors, but on the other, it was important for him that we should know what happened there."

A family heirloom

Shimon is now 61. He changed his family name years ago. Working for an organization that sends him overseas as an emissary, he was asked to change his name. He, sadly, changed his name to “Doron.” He’s the fifth, and perhaps the most stubborn, of six children born to the late Yosef and Bruria after their firstborn daughter was murdered in front of their eyes by the Nazis.

This shocking discovery about his parents as Jews in a concentration camp made when he was just 16, turned out to be the first of many, mostly after his father’s death, culminating in 1994 in his finding a treasure his father had hidden: a diary his father had kept while in Giado – the only surviving record of an inmate in the horror camp to which the Jews of Benghazi were sent.

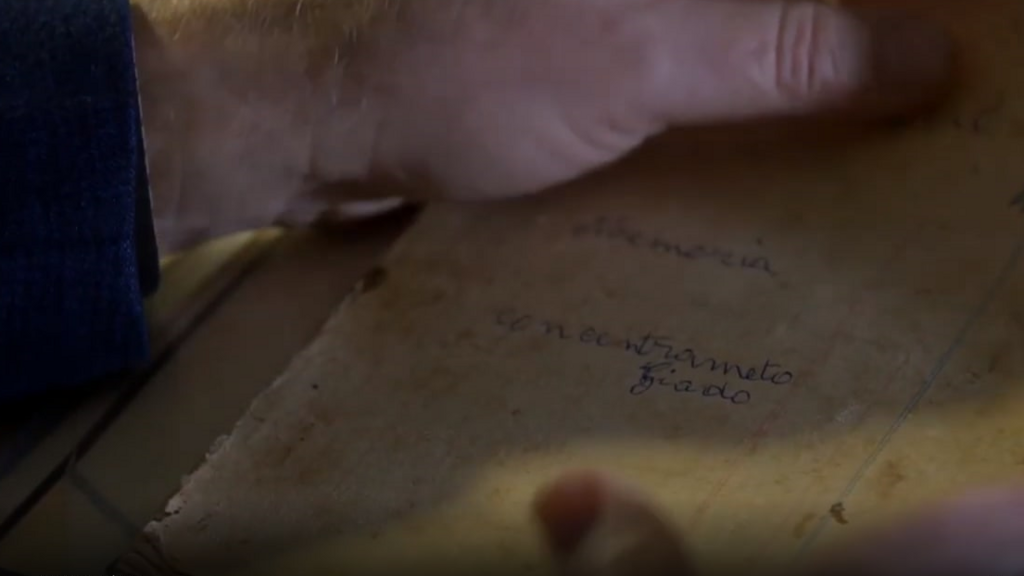

"There were a few words in Italian on the first page. I recognized one word - ‘Giado.’"

“Over the years, I kept asking my mother to open his cabinet. It was stuffed full of documents” he tells us. “I wanted to see what was in there. One evening, after asking to look through his files, my mother suddenly said ‘You know what, you can look in the cabinet’.”

Doron didn’t waste any time. He sat down at his parents’ dining table in Holon and started wading through the terrible documents. “At around midnight, I called to say I wasn’t coming home. I couldn’t stop.”

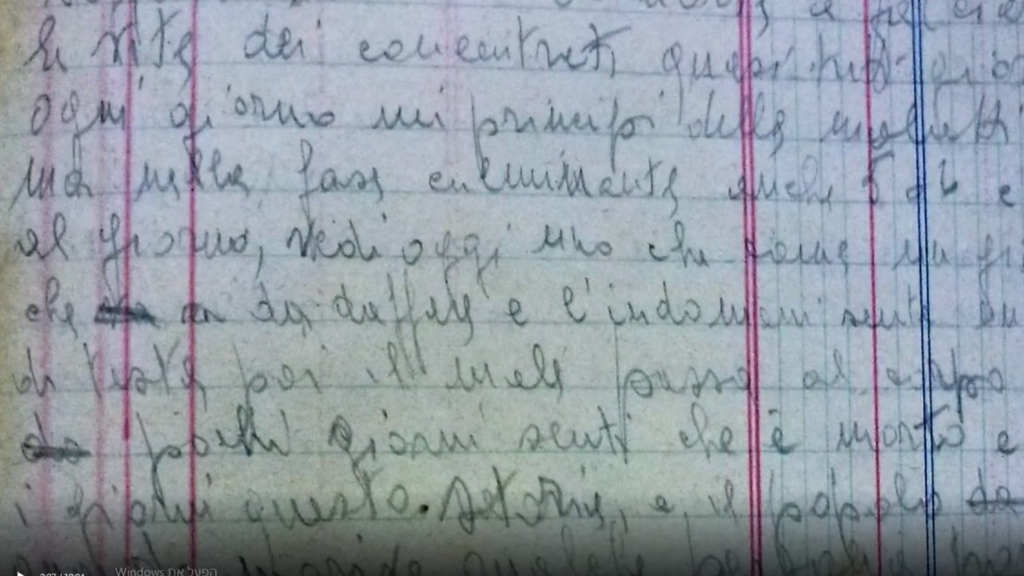

At about three in the morning, he found a notebook held together with torn strings. “It was written in Italian. The pages were sewn together with string. There were a few words in Italian on the first page. I recognized one word - ‘Giado.’ That was all I understood.”

The diary reads: “I did everything not to trip or stumble. I held back my tears. I now had one task: giving Ada a Jewish burial, but without my oppressors seeing my weakness, and without giving them the pleasure of mocking me as I choked on my tears.”

“We begin to understand that he risked his life every night. Under the watchful eye of the Nazi and Italian guards, he managed to write on pieces of paper that he got hold of here and there, in the full knowledge that he’d be shot if he was caught. And he never mentioned it. Never. He never mentioned the diary in any testimony or interview.”

Mother and son were holding in their hands crumbling pieces of paper with words that had faded with time. They knew they couldn’t stop now. They had to now decipher this rare document, to complete the history books about the 2,600 Jews of Cyrenaica who were forcibly transferred to Giado.

“At 6:30 am, my mother woke up. I showed her the notebook. She started reading it and burst into tears."

Doron contacted author and researcher, Shlomo Abramovich, who had written about the Jews of Libya and Dr. Yaakov Lattes, an expert on the Jews of Italy from the Renaissance period through to the present day. Lattes deciphered and translated as Abramovich wrote a book using the original diary text: “The hidden diary of Giado concentration camp” (published by Yedioth Ahronoth Books).

The book, published on International Holocaust Remembrance Day in January 2020 was an instant bestseller, drawing widespread interest among Muslim readers.

A Foreign Office Facebook post that he shared on his own Facebook page gleaned thousands of likes and shares as well as hundreds of comments from users across the Arab world including Libya, Egypt, Morocco, the Gulf states, and the Palestinian Authority.

Some expressed interest in the story, requesting the book be translated into Arabic. Other comments compared the Israeli occupation to that of the Nazis.

“At 6:30 am, my mother woke up. I showed her the notebook. She started reading it and burst into tears. Hardly able to speak, my mother translated the headings. She said ‘Your father wrote a diary in the camp and I didn’t even know.'”

Hunger, disease, and death

The faded manuscript, concealed by mold and oil stains, was brought to life: The terrifying reality of daily life in the concentration camp, how they were Benghazi Jews were taken from their homes and imprisoned in a concentration camp was now out in the open.

Yosef Dadush’s detailed descriptions draw a picture of horror, hunger, disease and death. In the same breath, he describes Jewish inmates in Giado "standing tall with determination in the face of abuse, humiliation and the danger of death.“

As they read their late father’s words, they realized quite how deceptive traumatic memory can be. What he’d heard at the lecture about his sister Ada’s murder didn’t even come close to what he’d written 75 years earlier.

Even in the Hell that was Giado, we were determined to give our loved ones a Jewish burial.

Firstly, he was only 21 at the time. “I needed a small wooden crate to bury Ada, but there were no crates in the camp,” writes Yosef that night. “Typhus had killed both children and adults at a terrifying rate, and the crates – large and small – had become a rare commodity. An hour later, I realized that I wouldn’t get hold of any kind of crate. I held dead Ada in my arms, and started walking towards the camp gates.”

With his mother, sisters and brother, Doron first read about their father’s horrific way to his daughter’s burial place: “I carried Ada in my arms from that terrible prison in the concentration camp to the 900-year-old Jewish cemetery. Even in the Hell that was Giado, we were determined to give our loved ones a Jewish burial.

"Accompanied by two Italian soldiers who were armed with pistols and holding brooms, I plodded through the sand. I did all I could not trip or stumble. I had one task – giving Ada a Jewish burial without my oppressors seeing my weakness, without giving them the pleasure of mocking me as I choked on my tears.“

“After walking for an hour in the desert heat, on what seemed like a never-ending path, I recognized the Jewish cemetery by the Hebrew writing on the gravestones. Among these tombstones, I looked for a place to bury Ada.

"I placed her lifeless body on the ground and frantically started digging a little hole with my bare hands. I dug, prayed and cried, but I begged mainly for forgiveness from my dead daughter. I asked myself over and over: Had I done everything possible to save her? When I thought the hole looked big enough and wide enough, I placed little Ada, wrapped up in sheets into it. I covered her with sand and mumbled the few burial prayers I could remember.”

Only after reading the final quote in Abramovich’s book did Doron understand that in addition to dealing with grief, his father also had to deal with feelings of guilt: Abramovich describes Yosef’s walk back to the camp after burying his daughter: “He waded through the dust of the desert that heavily covers every man and beast.”

“After walking for an hour in the desert heat, on what seemed like a never-ending path, I recognized the Jewish cemetery,"

Yosef vividly recounts in his diary a bitter argument he had with a fascist commandant for whom he had been forced to work as a bookkeeper. The commandant tried to help him, offering to use all his connections to keep him off the deportation list to Giado. Yosef refused. His fate would be with that of his exiled brothers.“

'Monsterous path of survival'

This wasn’t the last time that Yosef turned down the chance to flee with his family. When the same commandant once again offered to use his position to get him special permission to remain in Benghazi, he chose to leave with the rest of the community as part of the Final Solution dictated by the Germans, responding: “Where all my Jewish brothers are going, I’ll go too.”

This became a central theme on the opening page of Abramovich’s book, faithfully reflecting Dadush’s character as a leader.

“This tragic crossroads of decisions led Dadush to the monstrous path of survival in Giado,"

Abramovich concludes the terrible Dadush-the-father vs. Dadush-the-leader dilemma: “This tragic crossroads of decisions led Dadush to the monstrous path of survival in Giado, to the death of his infant daughter, Ada, and a daily life steeped in imprisonment and the struggle to survive.”

Mussolini surrendered to Hitler in 1938, legislating the “race laws” in Libya. In 1940, Italy joined the Second World War fighting alongside Hitler. In February on 1942, the deportation of the Jews of Cyrenaica/Benghazi to the Giado concentration camp as part of the Final Solution for the Jews of Libya began, setting off “dealing”, first with the Jews of Cyrenaica, and later those of Tripoli.

Libyan Jews holding British citizenship were transferred to the Innsbruck-Reichenau concentration camp, Bergen Belsen, camps in Tunisia and Italy and then onto camps in Germany. 562 Libyan Jews died in the concentration camp in Giado.

In 2021, after numerous unsuccessful attempts by Doron while serving as chairman of the Association of Jews from Libya in Israel, Dr. Orna Katz, head of history teaching in Israel’s Education Ministry, notified him that she recommends teaching parts of the book and that students will even be tested on them.

The fascinating diary, dense with horrifying events is written with sensitivity and love. Dadush describes the distress of the women in the camp, especially that of the widows and unmarried women who were subjected to sexual violence from the soldiers and officers.

"The Giado authorities instructed shaving the heads of all the men and of women up to the age of 12. It was an awful sight."

He describes his own attempts to help them however he could, and the play he wrote and performed for the inmates – as well as the money that was collected and donated to the weakest men and women in the community.

“A doctor arrived at the camp and declared that typhus had broken out in the camp,” writes Dadush. “This proclamation necessitated a lockdown of all sections of the camp. No exceptions. The Giado authorities instructed shaving the heads of all the men and of women up to the age of 12. It was an awful sight.

"Some inmates tried to get exemptions. I didn’t wait. Even before our turn in section H came around, I shaved my head myself. Then, all my friends in our section huddled together and did the same.”

'Every historian's dream'

Former journalist, Abramovich was quickly drawn into the hero’s character: “It was one more way for these guys to demonstrate to the camp authorities that they were keeping their dignity and their freedom of choice – even if it’s a simple decision – when and how to use their own bodies. It’s such an elementary and fundamental act of defiance.”

Abramovich believes that Dadush’s character is more powerful than the story itself: “It’s the writing of a man who, while struggling to survive, is careful about every detail and every conversation he holds. It’s every historian’s dream,“ he says.

“You understand the depth and strength of the Jewish community. You get an authentic glimpse into an undocumented piece of history. Through his writing, I felt that Dadush had a broad perspective of time. He’s a prisoner who understands that his horrifying experiences at the time will one day be part of history. “

This, Abramovich’s 21st book, is very different from his previous works: “This diary burned a hole in my heart. I’ve written about the Holocaust and about partisans. What you usually see are pictures of old people, survivors. You don’t really know what they looked like at the time.

"There were no photographs left after the camps. Here, something amazing happened. We found a photograph of him on a document from 1947. We enlarged it. Now, instead of the face of a wrinkled old man, I saw a good-looking, brave young man come to life. I felt I have a partner in my writing, that I’m alone, that he’s here with me. “

“The Hidden Diary of Giado Concentration Camp” (published by Yedioth Ahronoth Books).