Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

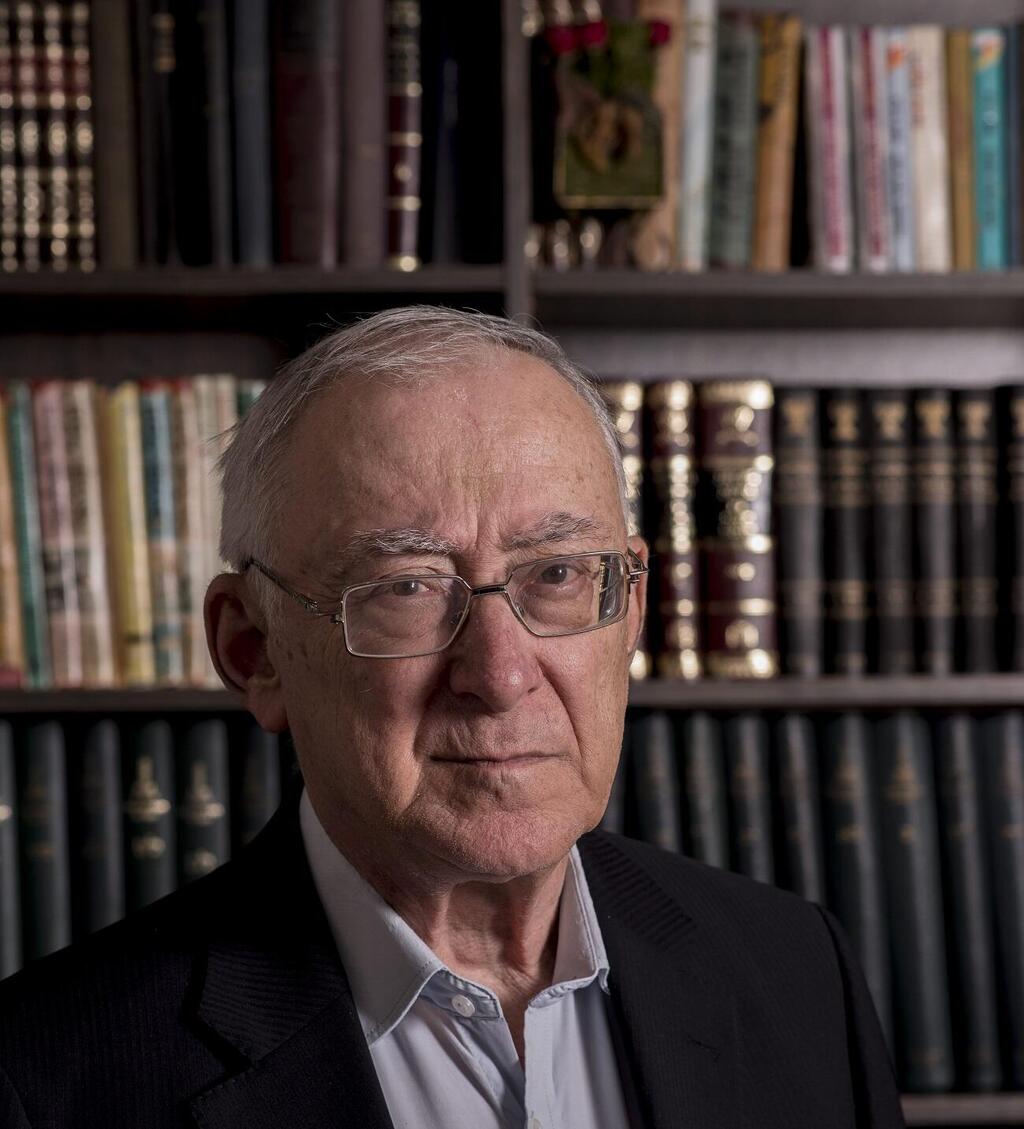

Under normal circumstances, a new book titled "Professional Jewish Ethics," dealing with Jewish ethics across various fields, including leadership, security and economics, would have received a warm public and media embrace, especially with authors like Israel Prize laureate Professor Emeritus Asa Kasher and his prominent student Dr. Tsuriel Rashi—a professional ethics expert and senior lecturer at the School of Communication at Ariel University.

But these are not normal days—Israel has been in a multi-front war since October 7, and Prof. Kasher, the author of the IDF's ethical code, recently said during a protest against the government that he believes the war should be ended and that soldiers are "falling in vain" because of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's political goals. Kasher also claimed that the phrase attributed to iconic Zionist activist Joseph Trumpeldor, "It is good to die for our country," is "foolish" because, in his words, "It is bad to die for our country."

When asked if, as one of the co-authors of the "Spirit of the IDF" document, he wants to clarify his statements or at least retract harsh comments he made against the settler community ("they are the murky ring within the soup"), he politely but firmly clarifies: "I do not want to retract, and I haven’t moved an inch from my opinions or how I expressed them. There is doubt whether Trumpeldor actually said the famous phrase, and in any case, immediately afterward, he asked if he was being evacuated to Kfar Giladi, meaning he didn’t want to die. But even if he did say 'It is good to die for our country,' I do not accept it in any way—dying is always bad, and it is also bad to die for our country. It is good to fight for our country and stay alive. Especially now, after so many soldiers have been killed, we understand how much we would have wanted them to fight for our country and return to their families."

You lost your son, Yehoraz, during his military service. How can you expect a soldier to risk their life?

"We explain to soldiers about commitment to the mission, and at the same time, we clarify that sometimes there is no choice, and in order to defend, we must send soldiers on dangerous missions, and unfortunately, they might get hurt or even die. This danger is unavoidable when we have enemies and wars, but it is never good to die for our country.

Regarding the demand to end the war—a democratic state must protect the lives of its citizens, and the question is which danger to prioritize and I say that the hostages are in extreme danger to their lives compared to other dangers that may arise from releasing prisoners or stopping the war, which are smaller and not immediate but rather distant, and the IDF and Shin Bet will handle them. Therefore, we must prioritize addressing the immediate danger and release them at any cost."

What do you mean by "at any cost"?

"Obviously, if Hamas were to ask for Tel Aviv as a gift, we wouldn’t agree, but within the context of ending the war and releasing prisoners, these are prices worth paying."

"The value of human life in Judaism is of utmost importance," notes Dr. Rashi. "Therefore, the question of releasing hostages is deep and broad, and the dilemma is more complex. The first question is whether it is possible to rescue the hostages, and then how much risk should be taken to do so. In risk management, we risk soldiers' lives to rescue hostages. For example, in the rescue operation where Superintendent Arnon Zamora was killed, the difference between a successful rescue and harming the entire force was razor-thin."

He adds that "The duty to care for others begins with the biblical prohibition 'You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor,' which is explained in the Talmud and further developed in rabbinical literature focusing on the extent of the risk one must take to save another. This issue has been addressed in responsa literature from 500 years ago up to modern-day authorities like Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. This certainly also influences the consideration of how many and which terrorists should be released in exchange for the hostages during negotiations."

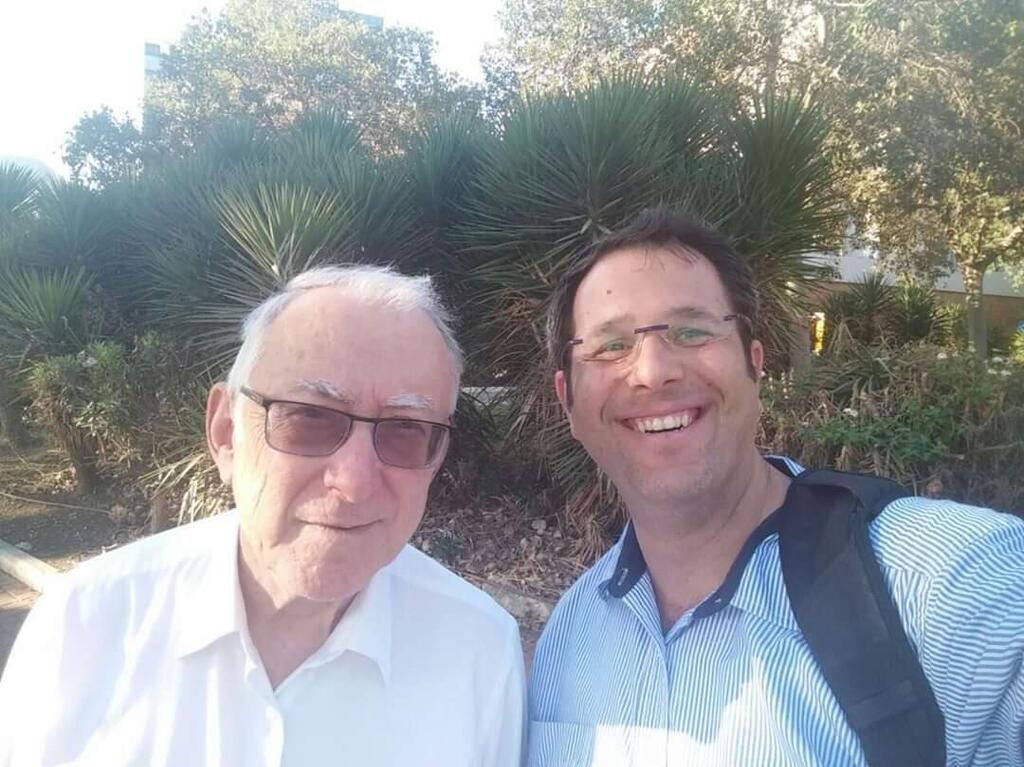

The reviewer who became a study partner

In 2007, Rashi completed his doctoral dissertation on "Communication and Media Ethics in Judaism: The Public’s Right to Know—Theory and Practice." Prof. Kasher was one of the reviewers who approved it. Afterward, Rashi suggested that Kasher become his "study partner" for joint study of Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers).

"While studying and delving into Pirkei Avot, I realized that we were circling around a single light at the end of the street," says Dr. Rashi. "I understood that there are many other significant sources of light. It turns out that Jews have always engaged in ethics and morality, even if they didn't call it by that name. This is evident from the Bible, through the Mishnah, Midrash, Aggadah, and not least in halakhic literature and responsa. Thus, as part of post-doctoral research, we continued to study and write a comprehensive book on professional ethics in Judaism over many years."

The book was published by the Bialik Institute and spans 756 pages. According to Rashi, "It essentially presents hundreds and thousands of sources from the Jewish bookshelf regarding the proper conduct of individuals and professionals. Over the 15 years we worked on the book, we repeatedly discovered how much Jews were concerned with the proper character of many professions—political, educational, and religious leadership, military and security, law, finance, physical and mental health, and more. This led to the understanding that alongside Jewish law, Jewish ethics stand strong. That's why we thought it appropriate to name the book Professional Jewish Ethics."

After researching and writing about Jewish ethics, do you think something should be changed in the IDF's ethical code?

"I remember being asked, 'What is Jewish about the Spirit of the IDF,'" replies Prof. Kasher, "and I think that the package of values in the ethical codes I was responsible for wouldn't have benefited from an artificial Jewish overlay added to the text. Look at the ethical codes in the armies of the world—there is no other ethical code that includes issues of the purity of arms and the value of human life as values, like there is in the IDF. The reason for this is that in Judaism, there is a tradition of restraining force, and the principle of saving a life overrides everything else to preserve human life."

"The concern for human life, even while risking oneself for others during war, is evident, for example, in the correspondence between Rabbi Kook and Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Pines during World War I, as well as in the writings of the first Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Isaac Herzog, and other rabbis," adds Dr. Rashi.

"This is a value that emerges from the Jewish bookshelf and should flourish within the Spirit of the IDF. Often in command courses in the security system, when I teach, I bring texts that analyze and deepen the understanding of various values such as comradeship or maintaining confidentiality, like Rabbi Solomon Ibn Gabirol's words: 'Your secret is your prisoner; if you reveal it, you will be its prisoner.' These texts are a kind of beacon that illuminates directions, allowing us to see much further and deeper into each value, and in essence, they also illuminate us."

Protesters in Jerusalem calling for the return of the hostages

(Video: Amit Shabi)

Was there anything that was left out of this hefty book?

"Certainly," replies Dr. Rashi with a burst of laughter. "There are so many fantastic sources in the Jewish bookshelf that didn't make it in. We had to stop somewhere. We also debated whether to include the chapter on media ethics—Prof. Kasher argued that journalism isn’t a profession and shouldn’t be treated as such, whereas I, having written my doctorate on media ethics, believed that especially today, when we all create and consume media, it’s important to discuss ethical perspectives. For example, Rabbi Israel Salanter’s words in the 19th century: 'Not everything one thinks - should be expressed, not everything expressed - should be written, and not everything written should be printed.'"

In the past two years, Israeli society has been torn apart by the debate over judicial reform and later by the demand to return the hostages at almost any cost. The obvious question is how these storms have affected them, and it turns out that Prof. Kasher's positions against the government and its leader have led to a social media attack against Dr. Rashi.

"I was very surprised that people attacked me just for engaging in dialogue and working with Prof. Kasher," he says. "Although the book was completed before the judicial changes began, people who hadn't even opened the book were sure it was already taking a stance, and that it was forbidden even to talk to those who think the opposite of them. To some people, I responded by quoting the words of the Maharal of Prague, who relies on Aristotle, stating that when a person is unwilling to be exposed to opposing views, it only reflects a lack of confidence in their own positions. With some of them, I realized—as someone who has taught rhetoric and debating for many years—that it wouldn't lead anywhere, so I simply disconnected from them."

Prof. Kasher says that, unlike his student, he did not face criticism for the collaboration that led to the creation of the book. "I have decades of professional activity in state institutions behind me, and I know how to separate political opinions from issues of morality and ethics," he says.

"When you read the book about values such as discipline, responsibility, and personal example, you can't tell which of us wrote those sections. It's possible to engage in the ethics of medicine or the Ministry of Defense without any politicization at all. We simply re-illuminated the corners that had gone unnoticed in the Jewish bookshelf."