Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

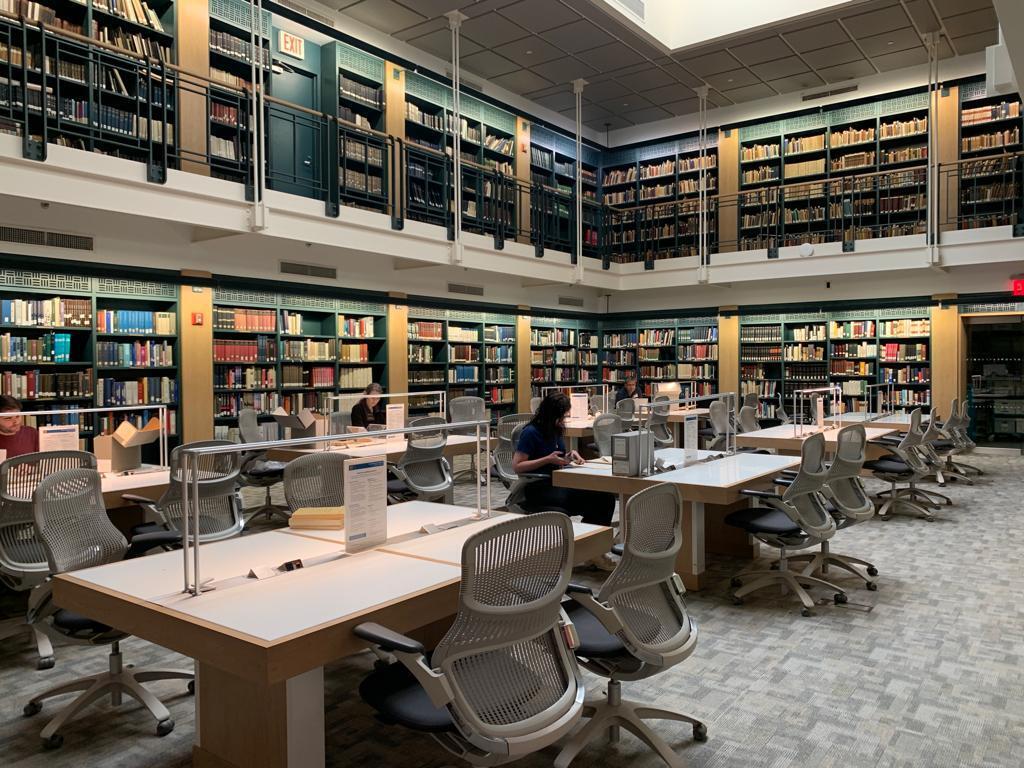

At the entrance to the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute in central Manhattan stands a massive mosaic made of tiles, each bearing handwritten letters in various languages. Together, they compose a map of the globe. It's artistic and impressive, but perhaps it would have been more fitting for the letters to form a warning sign: "Do not enter if you're not prepared for the results."

Read more:

For instance, like the case of yours truly, discovering that his family migrated from Cherkasy in Ukraine to Paris – not to nibble on a canelé by the Seine, but to Paris, Kentucky, the land of bourbon whiskey, to open a grocery store there. How typical.

But for those who can handle it, there's a real surprise waiting in the heart of Manhattan. Many are unaware that they can join Jewish celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow and Lea Michele, and thousands more who visit the Center for Jewish History annually to explore their family roots.

Here, with the help of the institute's experts, you can construct an illustrious family tree, and it doesn't matter if your lineage is from the East or the West, the United States, Israel or Iceland. Utilizing the largest Jewish archive outside of Israel, you might uncover details you'd never have imagined – and perhaps didn't want to.

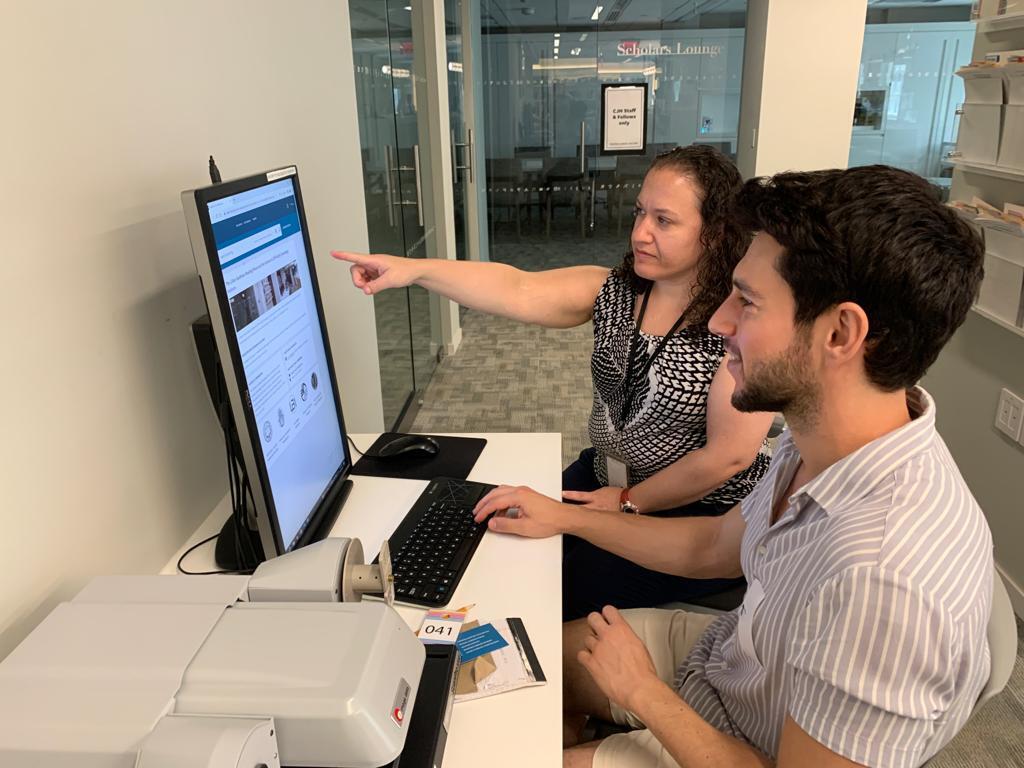

Here, Moriah Amit, 39, the chief genealogical librarian, or one of her colleagues, will guide you hand-in-hand through however many sessions you need, entirely for free. And there's no need to book an appointment in advance. Just pass the meticulous security at the entrance – as expected from a Jewish institution abroad – and be careful not to bring bags or pens inside for some reason (the institute will provide pencils).

The Family Genealogy Institute was established in 2007 thanks to the philanthropic support of local real estate magnates, the Ackman and Ziff families. The intention was to serve as a unified library for the vast archival records of the five partners that share the Center for Jewish History building - Yeshiva University Museum, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Leo Baeck Institute, the American Sephardi Federation and the American Jewish Historical Society.

Initially, the library was mainly used by students and researchers, but over the years it opened its doors to the general public. Today, it even features in various TV series focused on tracing roots, a sub-genre that has been flourishing in recent years on American television.

According to Amit, a diverse array of individuals come here: from writers and screenwriters seeking information on the fashion trends of the 18th-century Jewish town for their next Netflix hit, to people looking for lost relatives and, of course, documents and evidence for legal purposes, inheritance, immigration and more.

She mentions that there have been rare instances where living family members were found. However, most people discover relatives who perished in the Holocaust without leaving any records behind.

There are also many family members of orphans who come to find more detailed records about them or relatives of soldiers wanting to know where and in which battles they fought. Many military files from World War I and II were lost in a fire at the U.S. National Archive, and today, this institute is the only one that holds that information.

It's an emotional and moving journey, devoid of any cynicism. However, it's important to temper expectations from the outset: you won't leave here after an hour with a complete family tree. At best, you'll get a lead that still requires further nurturing and hours of work.

It turns out that even in the pre-social media era, every person had a complex and fascinating life story, along with dozens, if not hundreds, of records and documents that need to be reviewed. There is also a marked tendency for more documentation when it comes to Ashkenazi Americans. As we get closer to our time – particularly from the 1950s onward – the information becomes much less accessible due to progressive privacy laws. Still, it's New York City.

Most of the databases you access in the genealogy institute are also available from your home computer, but the assistance and guidance of the institute's experts have invaluable worth that can't be easily quantified. It's recommended to come prepared with some basic information, like family members' names, birth years and where they lived.

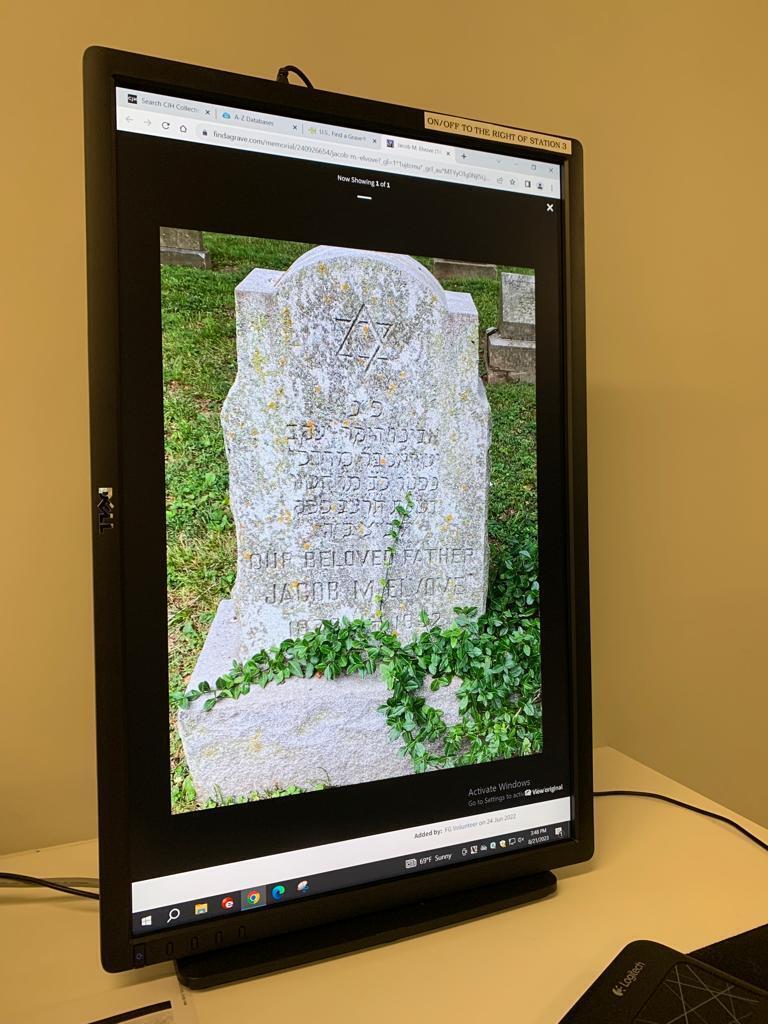

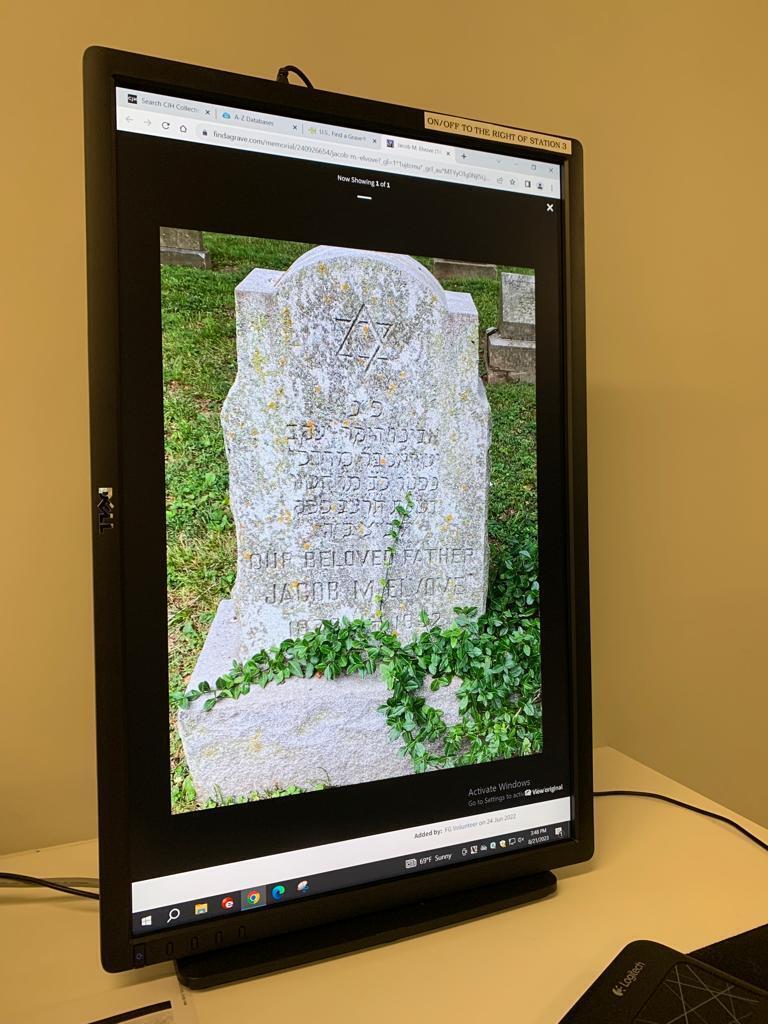

However, even with approximate information, the skilled Amit and her colleagues can work wonders. Within a few clicks, they might pull up a high-resolution image of a tombstone or a local newspaper clip about your great-grandmother's grand wedding.

In our case, we approached Amit armed with limited information that the Ashkenazi side of the family agreed to share. We expanded our search to include similar-sounding family names. This yielded 320 results, and we had to narrow it down.

After discovering the first name of my great-great-grandmother's husband in the records, we found a birth certificate and even records from the 1915 New York census. The records indicate that they immigrated from Russia, not Lithuania as we believed back home - given that the latter wasn't an independent country at the time.

According to the census, their occupation was listed as Jobber Bags. Even Amit herself wasn't sure about its exact meaning – it probably refers to workbag manufacturers. What mainly baffled me was where the property they lived on Madison Avenue had disappeared to?

When it came to the more rebellious side of the family that migrated all the way to Paris, Kentucky, we managed to find an old newspaper from the time and a book about prominent Jewish figures in the area (not particularly stiff competition), which shed some light on the mystery.

It turns out they migrated via Montreal, where there's someone in the lineage named “Easter" ("kinda sketchy," Moriah says), and their arrival in the promised land of Kentucky wasn't related to the Jewish Industrial Removal Office - the agency that sent Jewish immigrants at that time to the depths of the United States, kind of an early American version of resettlement programs.

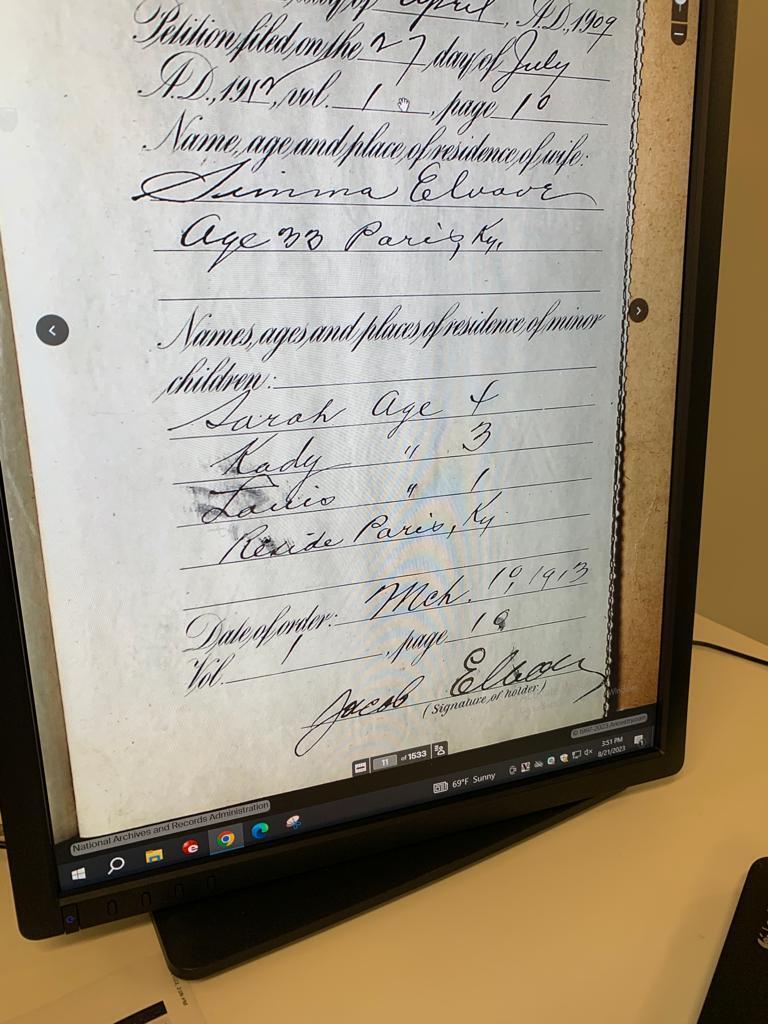

We did find a draft form for my great-grandfather for World War I when he was already 40, as the Americans expanded the draft to include everyone. Ultimately, he wasn't drafted, died of natural causes and we found photos of his gravestone as well as his naturalization certificate, complete with a signature in English.

According to Amit, this is a very rare find, perhaps rooted in a custom of that particular area in Kentucky. In general, it was rare for new immigrants to sign their names in English; they typically used initials due to language barriers. Either way, the question of what brought a Jewish family from Ukraine to the depths of Kentucky remains open, at least until our next research session.

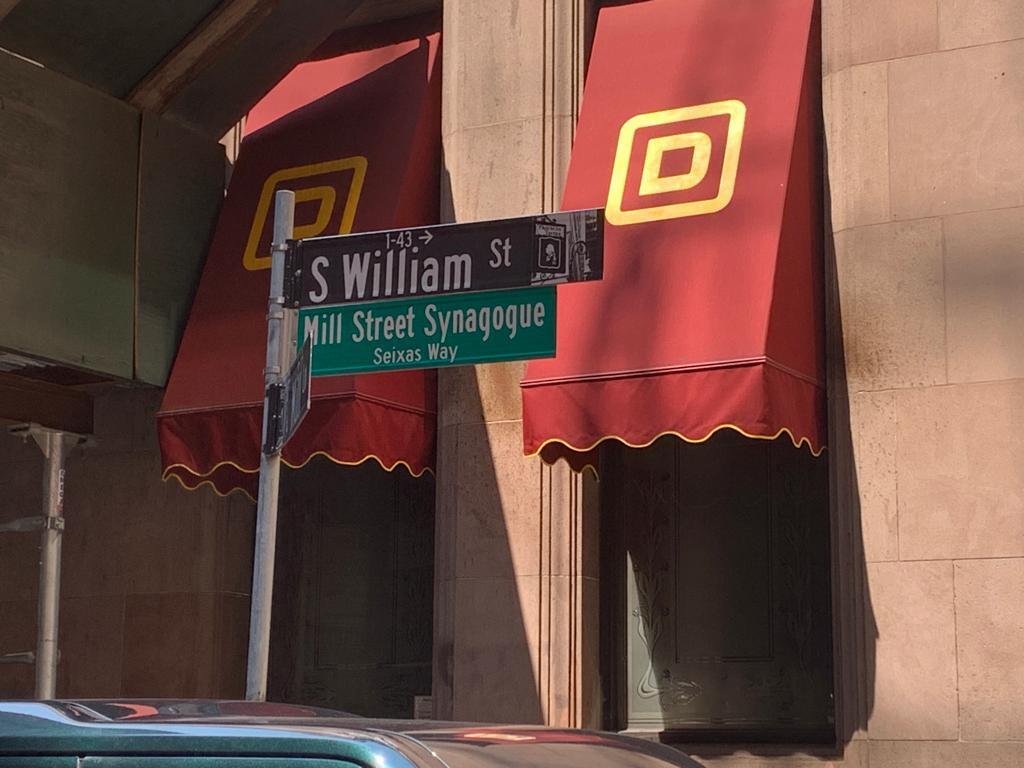

And speaking of exploring Jewish mysteries and roots, for those less interested in their immediate family and more in the roots of the nation, it's worth hopping a few subway stops south to the Lower East Side. Just about 100 years ago, it was still referred to as the "capital of the Jewish world."

9 View gallery

She even managed to find a high-res photo of my great-grandfather's gravestone

(Photo: Daniel Edelson)

Here lie the roots of several Jewish figures who became an integral part of the history of the United States. Asser Levy, Emma Lazarus and Uriah Levy - names that might not mean much to the average Israeli, but almost every child in New York could tell you about the first Jew who insisted on serving in the American army like everyone else, the Jewish poetess who dreamed of America so deeply that her poem was engraved on the Statue of Liberty or the first Jewish commodore in the American Navy. The lives of these legendary figures are intertwined with this area, which, in its prime, was home to one out of every three Jews in the world.

It's hard to believe that in 1664, only one Jew lived here. Asser Levy was a Sephardic Jew who arrived here, in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, about a decade earlier from Brazil, along with a group of other Jewish traders. They weren't granted citizenship, but that didn't really bother them - for them, the area was just another Caribbean island for trading cotton, sugar and of course, slaves.

In the meantime, while waiting to move to the next Caribbean island, they established a small community called Shearith Israel, which is considered the first established Jewish community in the United States.

Their synagogue (Orthodox, of course. The Reform and Conservative movements came much later with the Ashkenazi migration) was actually located in the Upper West Side, but another building in the Lower East Side is what brought Levy to prominence. Fort Amsterdam was a massive fortress that protected the colony, situated where today stands, fittingly, the National Museum of the American Indian.

In 1655, the governor of the Dutch colony, Peter Stuyvesant, decided to attack New Sweden, the Swedish settlement on the Delaware River. Consequently, he issued a conscription order for all the adults in the colony. The Jews, including Levy, were actually willing to serve.

However, the Dutch authority passed a clear directive not to allow any Jew to serve as a soldier but rather to pay a monthly "contribution" for the exemption. Levy and his companions refused to pay and appealed to the authorities, asking to be allowed to stand guard at the fortress like the rest of the townsmen - or to be exempted from the tax.

The appeal was rejected, with the justification that if the petitioners were not satisfied, they might as well move elsewhere. Indeed, most Jews got up and left. But Levy persisted, and after many nudges, he was finally allowed to perform guard duties at the fortress like all other citizens. This eventually led to equal rights for Jews. Thanks to Levy, the first law in the Western world was born that granted Jews equal rights.

Someone who benefited from this emancipation about two hundred years later was poet Emma Lazarus. Her father, a Jewish immigrant from Germany, was a well-established sugar merchant and a member of the Shearith Israel congregation.

Her family belonged to the upper-middle class, which allowed them to own a home in the city and spend their summer months in a vacation home in the northern part of the state. The family's economic status allowed Emma to be homeschooled and study music, European languages and literature.

She displayed a natural talent for poetry, and by the age of 17, her father published her poems in a 200-page book. Her writing consistently focused on various American issues, not on Judaism.

Lazarus, like the rest of her family, did not emphasize her Jewish identity. She attended synagogue mainly on Passover and Yom Kippur, and the rest of the time, she was fully immersed in American culture.

At a certain point in her youth, she volunteered to help in the assimilation of Jewish immigrants from Russia, sponsored by the city's wealthy Jews. This work inspired her to write the sonnet that now appears on the Statue of Liberty, and it also reconnected her with her Jewish identity.

She began studying Hebrew and became known as the "Jewish American national poet." The words of the poem itself, The New Colossus, which are engraved in stone on the base of the Statue of Liberty, serve as a powerful welcome to incoming immigrants and refugees, the poor and homeless, arriving in the United States to start anew, and perhaps to fulfill the American dream. "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

In fact, the poem was written as part of a fundraising campaign to complete the construction of the Statue of Liberty, which faced financial difficulties. The fundraiser approached Lazarus and asked her to write an original piece for an art exhibition intended to raise funds.

At first, Lazarus declined, stating that she doesn't write "on command or demand." However, after some persuasion, she got on board with the hope that the project would heighten public awareness about the issues faced by refugees arriving at the shores of New York.

After the fundraising event, the poem was published in limited circulation in local newspapers and was quickly forgotten. It wasn't even included in the statue's dedication in 1886. Only after Lazarus's death, as part of the effort to commemorate her and her contributions to immigrants, did the idea arise to place part of the poem on a bronze plaque within the statue's pedestal.

Today, the poem by the Jewish poet, who advocated for immigration, is taught in elementary and middle schools throughout the United States and has become a cornerstone of 20th-century American literature. And after all this, when one looks at the Statue of Liberty from the Lower East Side - the roots suddenly seem more exposed than ever.

The original manuscript of the poem can actually be found in the archives of the Center for Jewish History, as well as the first Records of “Shearith Israel.”