Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"For us, this is a sort of triumph. Reclaiming my grandfather’s honor. A kind of victory over evil," says Yaron Avidan, one of 18 Israelis and descendants of the Jews of the town of Końskie in southern Poland, who visited the town last week.

More stories:

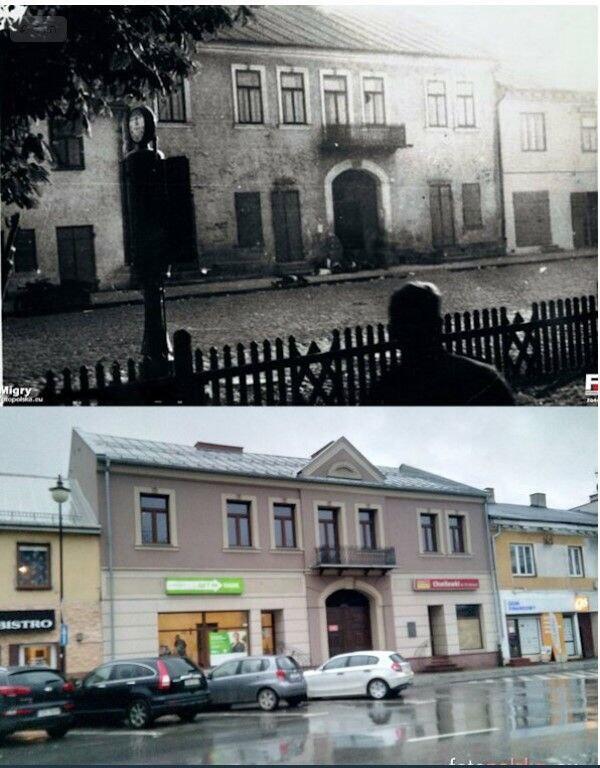

In 1939, the town was home to about 6,500 Jews, comprising about 60% of its total population at the time. Almost all of them perished at the hands of the Nazi Germans in the Treblinka extermination camp.

On September 9, 1939, six days after Końskie was captured, the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler visited the town at Tarnowskie Palace, where the 10th Army was stationed. Nazi propaganda filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl was supposed to document Hitler's visit there, but she missed it and arrived two days later.

A day afterward, she and her film crew documented a horrendous massacre of the town’s Jewry, where 22 Jewish men were murdered by Wehrmacht soldiers in retaliation for a revolt in which five German soldiers were killed.

Riefenstahl was appalled by the massacre and was even documented weeping. In her memoir, she wrote that she attempted to stop the massacre, but a German soldier threatened her with a gun.

After the war, only about 400 Jews remained from Końskie's Jewish community. Some returned to the town, but they were expelled under threats by their Polish neighbors. Yaron Avidan's grandfather, Sandor Eisenberg, was one of them. He wanted to take a Judaica item from his parents' house, but his neighbor threatened to sic dogs on him.

The town’s Jewry fled and never returned. "They didn't want to hear about Poland or the Polish," Avidan recounts.

In Israel, the descendants of Końskie's Jews maintained their community. They established an association, purchased a synagogue in southern Tel Aviv and established a community center that hosts family events around holidays, joint memorial events and more. They even made an effort to be buried next to one another and to buy from stores owned by those who lived in the town.

Over the years, a few of the town’s former residents returned for visits but received a cold shoulder every time, presumably out of fear that they wanted to reclaim their property.

Most of the survivors passed away

In recent years, most of the Holocaust survivors from Końskie have passed away. The second and third generations continue their commemoration and hold a memorial service for them every year. The younger generation established a WhatsApp group with 70 members to keep in touch.

Recently, one of the members suggested organizing a joint visit to Końskie and asked who would be willing to lead the initiative. Yaron Avidan stepped forward and approached Końskie's local municipality. He was uncertain about how his proposal would be received, but to his surprise, the town enthusiastically embraced the idea and agreed to host the group from Israel.

The visit’s purpose was to learn about the town’s history and to meet with its educators to explore how the town’s Jewish memory could be taught. "We didn't come to point fingers, but rather from genuine goodwill," explains Avidan. "We even asked if there's a religious figure who would agree to hold a memorial ceremony. Jews were a central part of this town.”

And so, members of the community visited Końskie together for the first time, where about 20,000 people live today. Deputy Mayor Krzysztof Jasinski and the city's councilors warmly welcomed them, and the local media documented the visit.

The main meeting took place in a room at Tarnowskie Palace, which is now owned by the municipality. School principals, researchers and historians from the city were also invited to the meeting. "We were amazed to discover that Hitler stayed in the exact same room where the event took place. I think there is no sweeter victory over the Nazis," says Avidan.

The town’s library team presented an extensive presentation to the Israelis about the history of the local Jewish community, revealing previously unknown information about the horrific massacre that took place there on September 12, 1939.

The library and the municipality collected information from the city's archives and found the names of the victims of that massacre, which was widely publicized around the world. They compiled a booklet with the names of the victims, their ages, professions, parents' names and copies of their death certificates.

The massacre was a German retort for the killing of five German soldiers, one of them a German officer. Initially, they imprisoned 5,000 of the town’s Jews and later released them. Afterward, soldiers took about 50 Jews and demanded that they dig graves using their hands for the German soldiers who were killed.

At a certain point, a German officer arrived at the scene and began opening fire at the Jews from his car. The Jews panicked and tried to flee. At this stage, the German soldiers started shooting at them, killing 22.

The names of most of the Jewish victims in the massacre were unknown. In recent years, an investigation was conducted into the event, which managed to discover the names of only three of the victims. When the Israelis planned the visit, they asked to know who was killed in the massacre – and the municipality conducted thorough research and managed to obtain all of their death certificates.

A prayer in Hebrew and Polish

At the Israelis' request, the town invited school principals to a meeting in order to cooperate with the group in creating joint learning programs about the Jewish community for students.

For the first time in the town's history, a joint memorial ceremony was held, attended by the town’s priest, city representatives and descendants of the Jewish community in the place where the ghetto once stood. Prayers were to commemorate the victims recited in Polish and Hebrew.

"The booklet with the victims’ names shocked us all. Until now, we didn't have their names. We didn't have comprehensive information about their age, profession and other details," says Avidan. "Their seriousness truly amazed us. It was very important for us that they mention part of the Jewish presence in the town, as it has been erased from their history.”

“The younger generation is interested in the Jewish community who used to live here. This can fix the relationship between the two peoples. My grandfather didn't want to hear this, but I feel that it's our generation's duty to renew these connections and promote dialogue against antisemitism."

"The booklet with the victims’ names shocked us all. Until now, we didn't have their names. We didn't have comprehensive information about their age, profession and other details"

"The municipality went out of its way to host us,” he says. "There were many curious locals who didn't understand what the visit was about, so they came to ask. Two older women from a local shop asked someone from our group who spoke Polish who we were and what we were doing. So, she told them that we’re descendants of Jews from Końskie and came to hold a memorial ceremony.”

“They then asked if we came to buy houses, to which we replied we only came to connect, establish friendly relations and learn about our ancestors' past together – and they reacted very positively."