Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The chubby ginger cat has lived in the neighborhood for as long as anyone can remember, even before it was fully inhabited. Despite his hefty physique, he bears a visible mark of disability: his meows are feeble and truncated, barely audible — something seems to have gone awry in his meowing. Despite his size, he's easily frightened, threatened, and intimidated by any random cat passing by. There's no way to pet him without feeling like you're petting thin air.

Read more:

Generally, I've maintained a peaceful coexistence with him until my daughter noticed him and started putting out cat food, which we didn't even keep because we don't have a cat. But now we do because she's making me buy it. It all started with a "just once, Dad, let's buy him food just once," and within half an hour, it became routine. Now the cat appeared on our doorstep every morning, patiently gazing inside, waiting for the daily miracle of the window opening and our little girl bringing out a plate of food.

At first, I thought to myself, "Okay, she'll give him food, and he'll leave." Then I thought, "Alright, she feeds him, and he leaves, but he'll be back tomorrow morning." Eventually, it dawned on me: the chubby ginger had claimed our balcony as his own, and he wasn't going anywhere! The creature simply planted himself by the balcony window and has since been staring inside — at us — 24/7.

I'd be in the kitchen fixing myself a small sandwich, and the ginger cat would gaze at me from outside with a look that says "I'm onto you." I'd cuddle up with my wife in front of the TV, and the cat would follow us with the curiosity of, you know who, and then shoot me a glance like, "Turn on Netflix, I've started watching a series there."

I could chase him away, but the repercussions would be great; my daughter wouldn't talk to me anymore, and worse: he'd be back in four minutes. "Not terrible," I told myself, "you'll learn to live with a stocky cat watching over you day and night." But then winter hit. The one from two weeks ago, the one that lasted two years. And the ginger cat was still there, on the balcony, damp, frozen, and miserable.

I felt sorry for him. I couldn't bear to see him like that and think that he was destined for another cold night outside. Heck, I opened the window and tried — with a "pssst" that lately only worked on Yasser Arafat — to coax him inside, to warmth. And just as the poor thing seemed tempted to give it a try, our dog intervened, charging forward with righteous indignation as if it were judgment day, and scared off the cat.

Well, she didn't exactly scare him off, but that's only because I got in between them, and she ended up knocking me over instead. Privileged, foolish dog.

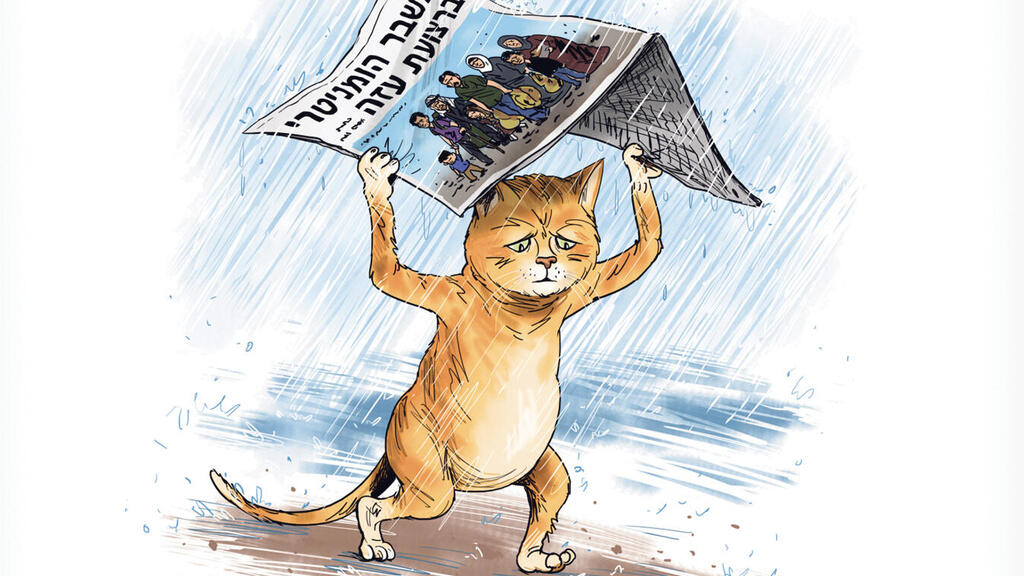

The next day, something strange happened to me in a similar yet different context: I read in the "Haaretz" newspaper about what was happening in Gaza City, among the ordinary residents, accompanied by an apocalyptic photo of a father and his two ragged children walking amidst ruins and rubble, clad in tattered clothes, carrying jerrycans of water, nylon bags, and whatever possessions they had left - along with an old children's bikes held by the father.

The report itself was no less harrowing: hunger for hundreds of thousands, extreme scarcity, exhaustion, no water except for filthy well water, no electricity or heating, a can of tuna selling for NIS 100, hunger driving people to bake bread from animal feed and flour.

I read this report from beginning to end, and I felt something strange that I've never felt before an automatic compassion that immediately shifted into a concentrated form of "your problem, you brought it upon yourselves, there's a reason and consequence, there's a price to pay". So, compassion turned — like boiling water poured into cold water — into some diluted, almost indifferent, feeble emotion, a sort of pain you're supposed to feel as a human being but someone injected a local anesthetic there, and the pain — if at all felt — became completely numb.

I tried to feel the pain, to dive into the basic compassion, and for brief moments, I somehow felt it, but then the feeling faded again, distanced itself from me, and turned from warm to cold. "They deserve it.' I was left with the knowledge that I was supposed to feel something that I simply can't feel right now when faced with images of children and adults suffering, hungry, and freezing just 65 kilometers away from me.

And I realized that the October 7 war took away from me — not because of me, but because of them this thing that we're all born with: general compassion, not the one directed at specific individuals, but just compassion for living beings wherever they are — and turned my compassion into a selective one. And in certain cases, one that barely exists.

This isn't where I thought I'd end up.

Because my daughter – like every young child in the world – still feels full, non-judgmental compassion towards everyone and everything. It's a new kind of compassion; one that allows you to empathize, from your perspective, with the pain and suffering of every living creature, and to empathize with them regardless of circumstances, outcomes, or context.

It's exactly the trait that enables creators to create, writers to write, doctors to heal, and social workers to assist. And it's exactly the thing that when it wanes and fades away from your life — due to life circumstances and the global numbness — you become less caring towards others. Indifferent, then selfish, and then, if it continues to escalate, you can become a psychopath and sometimes, to be a spokesperson for killers and rapists.

And I thought about all of this quickly, and then I moved on and haven't thought since about hundreds of thousands of hungry people in Gaza eating animal feed; I've thought endlessly about the 134 Israelis kidnapped, trapped, and held in Gaza, and about our exhausted soldiers are there and in the north, and about the weary families who were evacuated from their homes.

It's completely selective compassion.

And that's probably what October 7th did to people like me; not some great awakening (I'm still not in favor of the idea of forever ruling over millions of Palestinians within the framework of some "conflict management"; to my mind, they won't learn to love it, and neither will we), but from empathy to apathy, no longer having any understanding or compassion for the other side.

It wasn't supposed to happen to me, but here it is. Here I am also arguing that human choice has consequences and results, and yes, pitiful Palestinians, if you chose Hamas — and even if it forced itself upon you (seems plausible) — the consequences are what you're experiencing now.

Yet still, I have the right not to love this new indifference of mine towards suffering, even if it's justified. I have the right to understand that something in the primitive desire for revenge that's rising within me — especially when I recall the images of Shiri, Ariel, and Kfir Bibas at the moment of their abduction — detracts from my humanity. For better or for worse.

And then — and this is new to me — I have the right to move forward, to tell myself "Our compassion hasn't been lost yet" and to go feed the ginger cat because it's cold outside.