Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

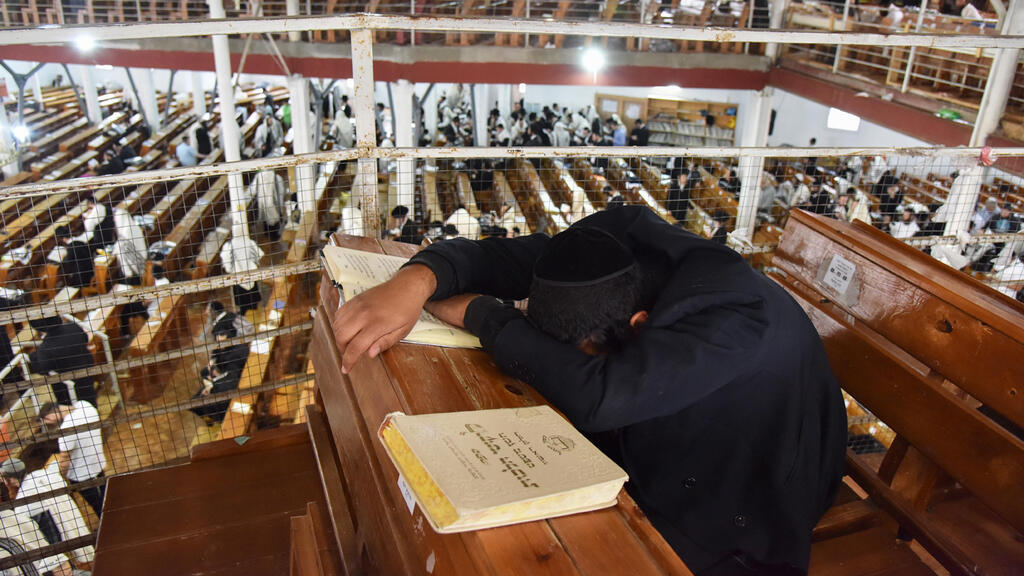

Under the specter of the ongoing war in Ukraine, Hassidim from all over the world flocked to the tomb of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov to celebrate Rosh Hashanah and the following holidays in mass prayer gatherings at “Zion Hakadosh” (“Holy Zion”) or at the “kibbutz” surrounding the gravesite.

It's been over 200 years since Rabbi Nachman's passing and the question as to when and whether his bones will be brought for burial in Israel is ever-present. Dozens of attempts have been made to bring his remains to a final resting place on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. Key Israeli political figures have tried to intervene. The Ukrainian authorities have fiercely refused, claiming that the tomb is a “national heritage site”, stressing that removing Rabbi Nachman’s bones from Uman is not on the cards.

Year after year, his followers, along with tourists from all over the world, continue flocking to Uman - filling Ukrainian coffers. It’s not just about Ukrainian interests: some Breslov Hassidim say that the rabbi wished to be buried in Uman and they oppose bringing his remains to Israel. Other Breslov Hassidim contend that these were the rabbi‘s wishes as long as the People of Israel were in Exile, and that the rabbi’s remains should now be brought to Israel.

Moshe, a Hassid spending his fifth Rosh Hashanah at the tomb of Rabbi Nachman in Ukraine explains: “If Rabbi Nachman’s bones weren’t here, it would mean huge financial loss for Ukraine. The site attracts visitors from all over the world, so why would they release the rabbi’s bones? We got through COVID. Now, we’ll get through the war in Ukraine. We’re not afraid. The rabbi is protecting us. All around us, there are bombings, but Uman is shielded.”

Six months before his death during the Sukkot holiday on 18th of Tishrei (October 16, 1810), Rabbi Nachman moved to Uman and told his followers that “Uman is the best place to be buried.” He promised that “Whoever comes to my grave and recites ten psalms (“HaTikkun HaKlali”, also known as The General Remedy - a group of ten psalms arranged by Rabbi Nachman for atonement for sins) and gives one pruta to charity in my name - even if his iniquities and, Heaven forbid his sins too, have grown stronger, then I will make every endeavor to save and correct him. Some say that the rabbi will pull him out of hell by his peyot (sidelocks.)”

The rabbi who, while still living, ensured that his followers spent Rosh Hashanah with him, claimed that this time has a “special power to sweeten the judgment.” Fulfilling the rabbi’s dying wishes, Hassidim visit his gravesite on Rosh Hashanah. Some spend the entire High Holy Days period through the month of Tishrei in Uman. During Soviet rule, Hassidim managed to make their way across Iron Curtain borders and later met the challenges of COVID to get to Uman.

A small Jewish community numbering a few hundred families, primarily earning their living from businesses providing services at the site, was recently set up not far from the tomb. The community is known as “The Israeli Uman.” They have been victims of the recent global rise in antisemitism: In December 2016, unidentified individuals threw a pig’s head engraved with a swastika into the tomb complex and poured red paint at the scene.

The Russian invasion of Ukrainian territory hasn’t deterred the faithful. Next to the tomb, the non-profit organization “Union Breslov in Uman”, which has been running the site since 2014, has set up a humanitarian aid center for the country’s refugees.

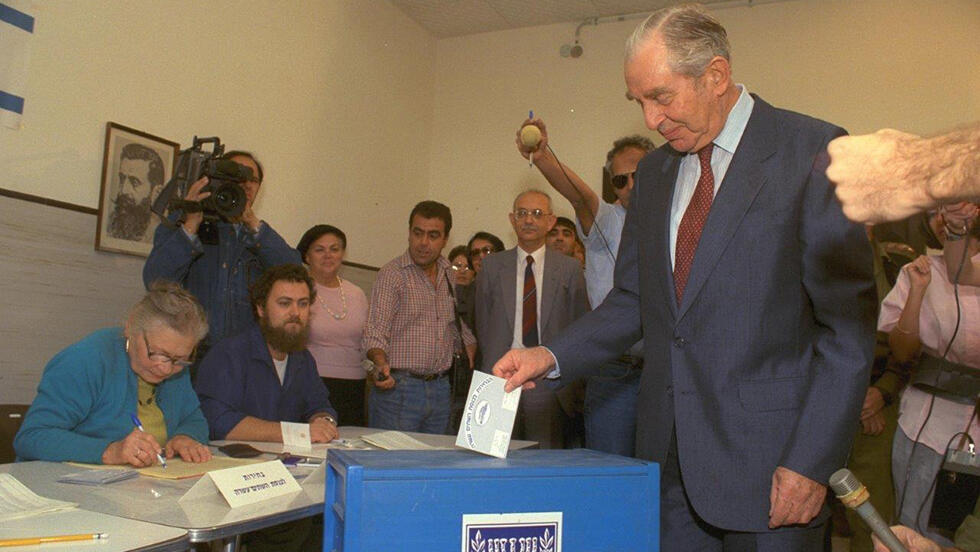

Hassidim wanting the rabbi’s remains to be brought to Israel include Rabbi Yisrael Dov Odesser (founder of the “Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman” subgroup within the Breslov Hassidim). In November 1992, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin asked President Chaim Herzog to request Ukrainian government intervention in the matter. At the beginning of 1993, Herzog submitted an official request, which was later resubmitted by Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. Years later, in 2017, then-deputy foreign minister Tzipi Hotovely confirmed that Israel had requested to bring Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel. The Ukrainian ambassador to Israel was quick to issue a denial, claiming that the matter was not up for discussion and that the gravesite is a “historical cultural site, part of the story of Ukrainian heritage.”

Then-president of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk stated that he was committed to allowing Rabbi Nachman’s remains to be released to be transferred to Israel. Following stern opposition by a large section of the Breslov Hassidim, including singer David Raphael Ben Ami, this commitment was rescinded. Towards the end of 2017, Breslov Hassidim calling themselves “Va'ad Tzion Rabbeinu in Eretz Israel” (“The Zion Committee for Our Rabbi in the Land of Israel”) initiated a public campaign using the tagline “Let My Rabbi Go”, evoking both Moses’ words to Pharoah and the campaign for Soviet Jewry’s right to emigrate to Israel.

“Release Rabbi Nachman to Israel,” the committee wrote to Ukraine’s prime minister. “Rabbi Nachman said ‘My place is only in the Land of Israel’.”

On August 17, 2020, with the pandemic in full swing, the Ukrainian government issued a statement regarding COVID guidelines for Rosh Hashanah. Internal documents revealed that the local Ministry of the Interior had halted the annual Hillula at Uman. New guidelines dictated that there would be no commercial flights in or out of Ukraine. The Hassidim would have no choice but to obey these strict guidelines. Breaking these rules would be met with expulsion from the country and a three-year prohibition on entering Ukraine.

An urgent petition was filed to Israel’s High Court of Justice demanding a probationary order that Israel’s government should instruct the Jewish Agency to take measures to bring Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel. The petition was filed by MK Itamar Ben Gvir Adv. for Breslov Hassid Rabbi Sharon Tel-Tsur who had been very active on the matter.

The petition reads that it was filed “because an asset of the Jewish People – the grave of Rabbi Nachman, visited by many Israelis for prayer – is under foreign rule which holds it without permission.” The petition further stressed the potential spiritual, economic and tourist growth that bringing the remains to Israel could create.

“Rabbi Nachman is buried on soil in Uman, where 30,000 Jews died in sanctification of Hashem. That is where Rabbi Nachman chose to be buried. The time has come to reinter him to the tomb of King David from whom he is descended. The Star of David is the symbol of the Jewish People. It belongs to the People of Israel. It’s a national asset which must be returned to its natural place.”

In response, Supreme Court Justice Daphne Barak-Erez instructed then-prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli government and the Jewish Agency to respond to the petition, explaining why they were not taking steps to bring the rabbi’s remains to Israel, as outlined in the petition. The petition was later denied.

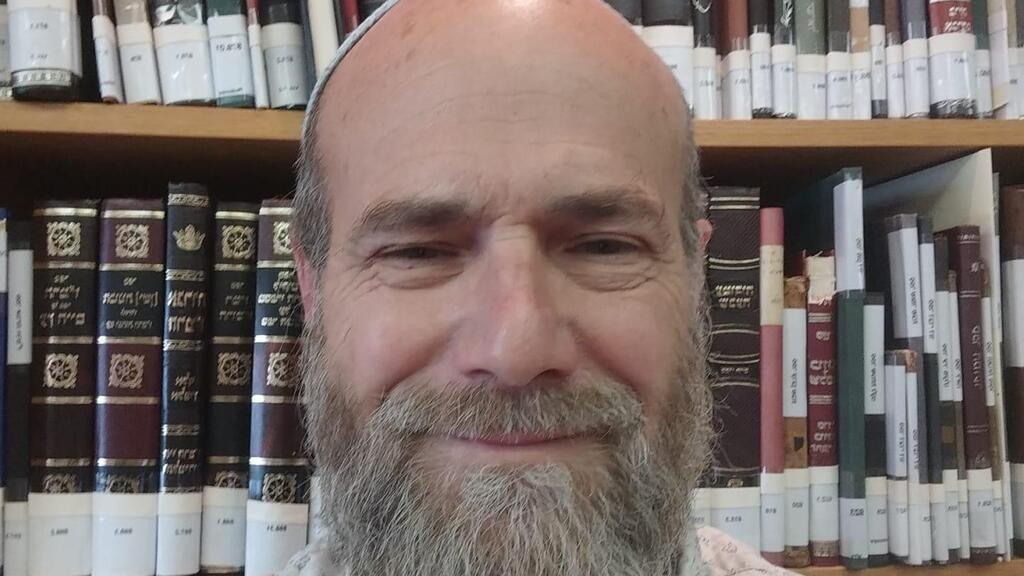

Hassidic movement researcher and published author Dr. Zvi Leshem explains the motives behind the Breslov movement which attracts large numbers both in Israel and throughout the Diaspora: “On a personal level, I feel a great affinity to Breslov and Uman, but don’t feel connected to Israelis leaving Israel to go live there. Although the surrounding area is lovely, the Jewish neighborhood near the gravesite is kind of a dirty, panhandler-ridden slum. I feel like going there, praying and leaving.”

Leshem, director of the Gershom Scholem Collection for Research in Kabbalah and Hassidism at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, adds that “Rabbi Nachman has become a popular cultural icon who has been the subject of much academic research. In the absence of a successor, this branch of Hassidism has no central, authoritative leadership – so it’s a movement without a leader.”

He mentions that until 20 years ago, the tomb site was very small: “It’s in the yard of a Ukrainian family living next to the old cemetery. It then became a rather simple site, and now it’s a huge complex with a large synagogue, mikva and beit midrash. The Jewish neighborhood of mostly Israeli followers surrounds the site.”

“There are grocery stores, restaurants, shops selling religious books, Rabbi Nachman souvenirs, hotels and hostels, educational institutions for children and more. Although tourism brings in large amounts of money for the town, it can sometimes cause friction between the Hassidim and the locals.”

Rabbi Nachman himself paid a year-long visit to the Land of Israel in 1798-9. “Likutei Etzot” (“Advice”) 1826, based on sayings of Rabbi Nachman quotes him saying: “The right mind and thought are only from Eretz Yisrael.”

Dr. Leshem clarifies: “When Nachman returned home to Ukraine, he was very active in encouraging his followers to move to Eretz Israel, so there’s a group within the Breslov Hassidim that claims that when he told his followers to move to Uman, it was aimed at people from the surrounding region in Ukraine, and not intended for people to leave Eretz Israel. It’s a hard call to make, especially as there’s a kind of anarchy within the Breslov community so there’s no one who could really determine it. On the other hand, this is exactly what makes Breslov so attractive not only for Hassidim, but for Jews from all sectors of society, including secular people. Uman has become a spiritual, not necessarily religious, experience.”

Moshe Lior (25) from Tsfat, who served in Netzah Yehuda Batallion - the IDF’s combat unit for Haredi men - says that he has been visiting Uman “from a very early age.” He says that two years ago, during COVID, "we got stuck on the way and we spent Rosh Hashanah in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. I also pop over to visit Rabbi Nachman during the year. This is my 23rd time here.” He explains that “the energy here is crazy this year. It’s both a physical and a spiritual journey. The physical journey is important and gives meaning to this mass gathering of people. It’s not like you get up in the morning, go to the grave and go back home.”

“A lot of people searching for God in this crazy world have discovered that there’s a rabbi who reached an insane level of true accomplishments.” He further explains: “He said ‘Ish Bal Ya’eder’ (‘No man shall be absent’) that Rosh Hashanah ranks above everything else for him, so even if it’s an amazing super-cool religious festival experience with all kinds of Jews from all over the world, we come mainly because the rabbi ordered us to. He reassures us on a daily basis and the Torah that he brought to the world keeps our heads above water.”

Apart from the absence of Ukrainian men who have been drafted, he says that the war wasn't really felt around the site. “Our apartment is owned by a 35-year-old mother-of-two whose husband is on the front line and she‘s been left to fend for herself, supporting and taking care of the children.” Two Jewish Ukrainian soldiers stopped his car on his way to Uman. They had “Magen Israel” written on their shoulders. The two, Ariel and Tomer, told us that they had been pulled from the front line to serve near Uman as they speak Hebrew. “It was great bumping into them in the middle of nowhere.”

Much of what we know about Rabbi Nachman is thanks to his adherent, Rabbi Natan Sternharz of Nerimov, de facto leader of Breslov Hassidism, who continued disseminating Rabbi Nachman’s teachings following the rabbi’s death. Rabbi Sternharz recorded Rabbi Nachman’s biography and sayings in great detail, including posthumously written legends involving angels, princes, ships and adventures which gained great popularity and influenced modern Jewish writers, including Franz Kafka.

We know that he came from the small town of Mezhybozhe in Eastern Ukraine and that his wife Sashia died of tuberculosis and that at least one of his seven children also contracted the illness. In time, Rabbi Nachman himself also eventually caught tuberculosis.

As doctors exhausted all options and the rabbi knew he was about to die, he moved to the large nearby town of Uman so as to be buried in the town’s old cemetery alongside 30,000 Jews killed in pogroms. He spent his final months in Uman.

Dr. Leshem points out that “it’s interesting to mention that he spent much of his time towards the end of his life with Uman’s intellectuals rather than with the Hassidim. This seemed rather odd to them.” He adds that Hassidim would gather around Rabbi Nachman on special occasions such as Rosh Hashanah, Shavuot, and the Shabbat during Hannuka. Rabbi Nachman requested that they continue gathering around his grave following his death. This is how the journeys to Uman began.

Dr. Leshem continues: "The Breslov movement was still a small, marginal group in the Hassidic landscape back then. The spread and strengthening of Hassidism verge on revolutionary. The Communist Revolution, the Iron Curtain and Soviet Union’s aversion to religion and Jews, in general, made it hard to get to Uman. No more than a few dozen made it. Between the first and second world wars, Breslov Hassidim would gather at the ‘Hokhmei Lublin’ yeshiva in neighboring Poland, creating the ‘kibbutz’. With the fall of Communism and of the Iron Curtain, these Hassidim brought back the tradition and started flocking to the gravesite.”

Alexandra Mandelbaum Kupeev is currently finishing up a Ph.D. dissertation at Ben Gurion University titled “Holy Tuberculosis”, focusing on the 19th-century development of Breslov Hassidism. She also addresses the ongoing efforts by a group within the Breslov Hassidim to bring the remains of their founding rabbi to Israel. She has studied records and documents in Israel’s State Archives detailing their correspondence with state officials. She says that they “earned warm and sincere responses.”

She mentions David Assaf who was the first to deal with the polemic regarding bringing Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel. He collected pamphlets dealing with the issue and even found an early account of one of the campaign initiators, Sharon Tel-Tsur. “The efforts to bring Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel have been aggressive, stubborn and persistent.” She mentions Rabbi Yisrael Dov Odesser who, in the 1970s, conducted correspondence with then President Zalman Shazar who allocated an annual grant to Odesser and his yeshiva.

In the 1990s, Rabbi Odesser wrote letters with Tel-Tsur asking for action to be taken, arguing that just as the state had gone to great efforts to bring the remains of leading Zionist figures such as Zeev Jabotinsky, Theodor Herzl, Moses Montefiore and other individuals of public note, the same policy should be applied to the remains of Rabbi Nachman. Mandelbaum Kupeev believes that “the State of Israel officially bringing the remains to the country is not only the sole diplomatic course of action, but would also constitutes a national recognition of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov as a national hero.”

Yitzhak Rabin, Chaim Herzog, Shimon Peres, Ariel Sharon and former president Moshe Katzav all received requests to address the matter. These pleas were always accompanied by two quotes: The first, from “Chayey Moharan”, Rabbi Natan Sternharz of Nerimov’s biography of Rabbi Nachman: “Rabbi Nachman of Breslov would say ‘My place is in the Land of Israel. Wherever I travel, I’m only traveling to the Land of Israel’.” The second quote is from a diary kept by Rabbi Natan: “And he said he ‘would like to go to Eretz Israel and die there, but he is afraid that he will not be able to get there. Even if he dies there, no people will come to his grave and no one will tend his grave’."

Mandelbaum Kupeev found a document highlighting sectarianism among the Breslov Hassidim. A letter sent on January 12, 1993, to then-president Chaim Herzog signed by “The Breslov Hassidim” reads: “As for the opposition by the group called ‘Va'ad Tzion Rabbeinu in Eretz Israel’ (the group opposing bringing Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel), we emphasize that this group is neither legal nor ethical because: a. Elections have never been held by anyone anywhere and no one has elected them. b. Breslov Hassidim have never had an official leader and c. The aforementioned group is just made up of a few self-appointed people with good press who have given themselves roles and titles. Everything cited above can be verified.”

The letter further reads “It is well known that Rabbi Nachman deeply wished to be buried in the Land of Israel, as testified by his student Rabbi Natan Sternharz in several places in his book. He had no choice (which in the interests of time, we shan’t detail) but to ask to be buried in Uman. None of the Breslov Hassidim own the tomb of Rabbi Nachman more than he himself, who wanted to be buried in the Land of Israel... Let us strengthen and adopt the great mitzvah of bringing his holy grave to Israel, for the joy and well-being of all the adherents and followers of the Rabbi of Breslov. Sincerely, Breslov Hassidim, signed ‘The Hasidim who support the bringing the rabbis’ remains to Israel’.”

Mandelbaum Kupeev explains: “Odesser’s followers are protesting against another Breslov group, who could very well make the very same accusation about Odesser’s adherents. This schism highlights the different streams within the river that is Breslov Hassidism. It’s a river which breaks off in various different directions while containing opposing religious movements.”

Dr. Leshem points out that the opposition of some of the Breslov Hassidim to bringing the rabbi’s remains to Israel is not rooted in opposition to Zionism: “Yes, some of the people who wanted to bring the remains to Israel were followers of Rabbi Odesser, the “Na Nach Nachma Nachman Me’uman.” They are, in some ways, more Zionist and less Haredi. They’re therefore more likely to think that if the option would have been available at the time, Rabbi Nachman would have wanted to be buried in Israel. However, the more conservative group within Breslov are simply more prone to conservative interpretation and take fewer risks. They say ‘He wanted to be buried in Uman’ and stick with this interpretation.”

The subject surfaces every now and then. But at least for now, bringing Rabbi Nachman’s remains to Israel doesn’t seem to be on the horizon. As long as that is the case, it looks like thousands of Breslov Hassidim and others will carry on visiting Uman searching for a spiritual experience or inspiration from the Zaddik.