Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The people of Israel left Egypt twice, so to speak. According to Jewish tradition, after Jacob and his sons went down to Egypt, their descendants were enslaved by the pharaohs. About 3,300 years ago, after a long period of enslavement, they made their first exodus from Egypt.

In 586 BCE, following the destruction of the First Temple, many Jews, led by the prophet Jeremiah, migrated to Egypt. For over 2,500 years, a vibrant and illustrious Jewish community thrived there.

However, as the State of Israel was taking shape and over the next two decades, the Egyptian government made life increasingly difficult for Jews. This led to a second and final exodus from Egypt, with most Jews immigrating to Israel, and others dispersing primarily to the United States, France, Argentina and Brazil.

With the help of the International Organization of Jews from Egypt, headed by Levana Zamir, and supported by the Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization, we have assembled a puzzle that offers a glimpse into the history of this distinguished and ancient community from the beginning of the last century, highlighting the challenges that led to their second and final exodus.

Fleeing Eretz Yisrael to Egypt

In 1915, during the height of World War I, it might be hard to believe, but Jews saw Egypt as a safer refuge than the Land of Israel. That year, Jewish refugees from the Land of Israel arrived in Egypt aboard the American warship Tanas.

15 View gallery

Jews en route from the Land of Israel to Egypt, 1915

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

The Zion Mule Corps

That same year, not only refugees but Jewish soldiers reached Egypt. A year earlier, Revisionist Zionist leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky proposed the formation of Jewish legions within the British Army under King George V.

15 View gallery

The Zion Mule Corps, 1915

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

The first of these Hebrew legions, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Patterson with Joseph Trumpeldor second-in-command, was the Zion Mule Corps. Initially, the unit fought in Gallipoli, Turkey, before moving to Egypt, greatly impressing the local Jewish community.

When in Egypt, do as the Egyptians do

The Jews in early 20th-century Egypt, like those in other diasporas, were not a homogenous group. Many dressed European-style and spoke French. However, some subscribed to the old adage "When in Rome, do as the Romans do"; in Egypt, they wore galabiyas and fezes like their Arab neighbors.

15 View gallery

Egyptian Jews wearing galabiyas and fezes

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

When Sharett was Chertok

During World War II, some 30,000 Jews from the Land of Israel, constituting about 10% of the region's Jewish population, enlisted in the British Army. Many were stationed in Egypt.

15 View gallery

Moshe Chertok (center), later known as Sharett, visiting Egypt during World War II

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

In 1943, then-secretary of the Jewish Agency's political department Moshe Chertok visited to check on their welfare. Chertok later changed his last name to Sharett and became the second prime minister of Israel.

However, it was the first lady of Hebrew theater Hanna Rovina who truly lifted the soldiers' spirits with her visit in 1944.

Maccabi Alexandria All-Stars

Following the Nazis' failure to conquer Egypt, the local Jewish community thrived. Official records listed about 66,000 Jews in the country, a fifth of whom held Egyptian citizenship, with the rest being stateless or holding foreign passports, primarily Italian, British and French. Most Jews rendered financial services like commerce and banking and were well-off.

The community's liberalism was so pronounced that young Jewish women, like those seen in an old photograph from 1947, joined Maccabi Alexandria, a popular and dominant soccer team at the time.

However, by the end of that year, ominous winds started blowing down the Nile. Youssef Haikal Pasha, a member of the Egyptian mission to the United Nations, declared, "Jews live in peace in Egypt and enjoy all civil rights... If the United Nations decides to partition Palestine, it will bear responsibility for severe troubles and the massacre of many Jews."

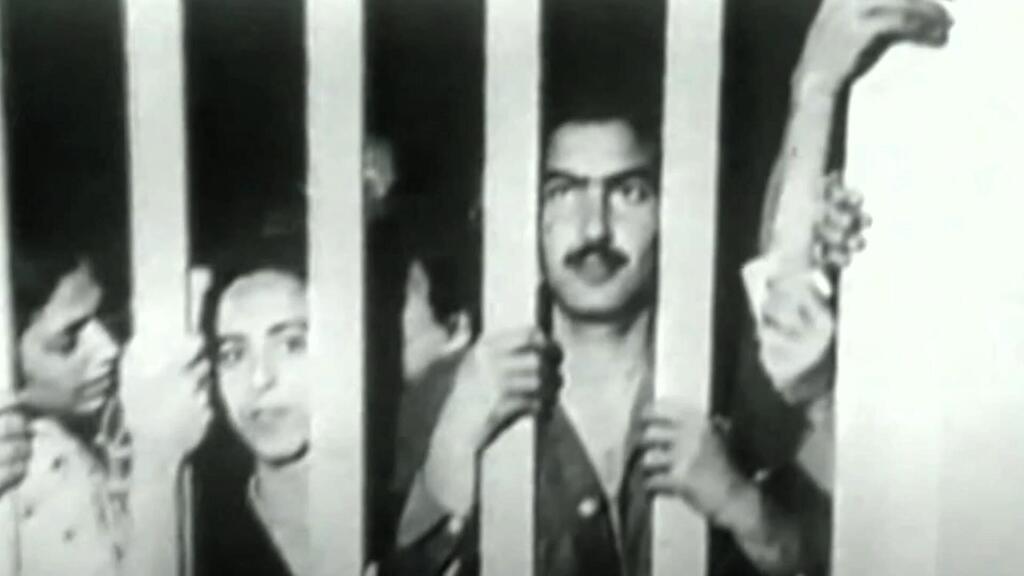

The nightmare after the creation of Israel

With the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, Egypt dispatched troops to join the Arab invasion of the nascent country. In retaliation, the Egyptian government targeted its own Jewish population; over 1,300 Jewish men and 50 women were detained without trial for eighteen months. Their properties were seized, and most were only released on the condition that they leave the country immediately, stripped of their possessions.

15 View gallery

Egyptian Jews incarcerated after Israel's creation

(Photo: Courtesy of the International Organization of Jews from Egypt)

Following the Egyptian army's defeat in the War of Independence, hostilities toward Jews intensified, including the bombing of Cairo’s Jewish-Karaite quarter that killed dozens.

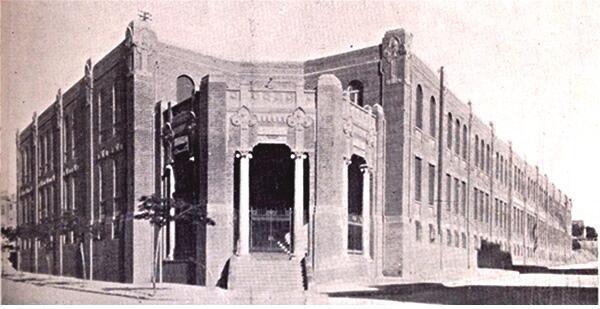

Quadrilingual schools

Despite these adversities, many Jews struggled to leave the thriving communities of Cairo and Alexandria, which boasted no less than 16 large and modern schools, such as the Abassiya in Cairo.

The grandeur and elegance of the building alone signified a wealthy, prestigious educational institution. "The children learned four languages there—French, English, Arabic and Hebrew," proudly recounts Zamir.

Studying with nuns

Despite their connection to heritage, many Jews in Cairo preferred to send their children to mission schools due to their high standards. "That's because they were top-notch," Zamir says with a smile.

"The photo shows Jewish students at a nunnery school in Helwan, south of Cairo, taken in 1949 before the expulsion of the Jews."

15 View gallery

Jewish students at the Christian mission school in Helwan City

(Photo: Courtesy of Levana Zamir)

Hebrew classes in Talmud Torah

Levana Zamir, née Vidal, and her siblings received a secular education but attended Talmud Torah in the city of Helwan, managed by Joseph and Esther Azulay (pictured), twice a week for Hebrew lessons and Shabbat psalms sung in synagogue on Friday evenings.

15 View gallery

Jewish students at the Talmud Torah in Helwan City

(Photo: Courtesy of Levana Zamir)

Zamir recounts how Jews coped with hostilities. "In 1949, on the bus to school, my older brother David was beaten bloody by Arab boys. By chance, his good friend, a Muslim named Muhammad Jazar, boarded the bus and convinced the boys that my brother was also Muslim, saving his life."

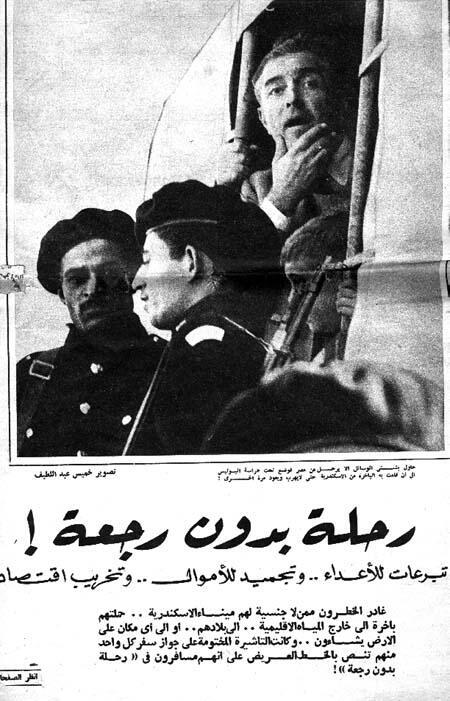

Exit, with no return

On October 29, 1956, the Suez crisis erupted, and the Egyptian government facilitated widespread attacks on Jews. In November 1956, President Gamal Abdel Nasser signed a decree allowing for the confiscation of Jewish properties; hundreds of businesses were seized and many bank accounts were frozen.

15 View gallery

'Exit, with no return,' reads Egyptian newspaper headline

(Photo: Courtesy of the International Organization of Jews from Egypt)

The Jewish community began to disintegrate—community institutions were silenced, their funds were frozen and key community buildings like the Jewish Hospital in Cairo were commandeered by the Egyptian army.

"Exit, with no return," read an Egyptian newspaper headline in November 1956. This headline was taken from the text stamped on the passports of Jews who were expelled or forced to leave Egypt between 1956 and 1957. Additionally, Jews were forced to sign a declaration that they would never return to Egypt and had no claims against the state.

Emergency assemblies for the rescue of Egypt's Jews

Israel’s successful military campaign during the Suez Crisis and the relative ease with which the IDF managed to seize large swaths of Egyptian soil stirred a sense of euphoria in the young, embattled country. However, the results of the war concerned the Sephardic Jewish community residing in Jerusalem.

Posters and flyers displayed on notice boards and homes read, "Emergency assemblies by the Sephardic Community Committee of Jerusalem for the rescue of the Jews of Egypt."

Jerusalemites were urged to gather in synagogues, "where representatives of the Sephardic community in Jerusalem will protest against the destructive actions of the Egyptian tyrant Nasser and express our solidarity with the demands of the Knesset and the government."

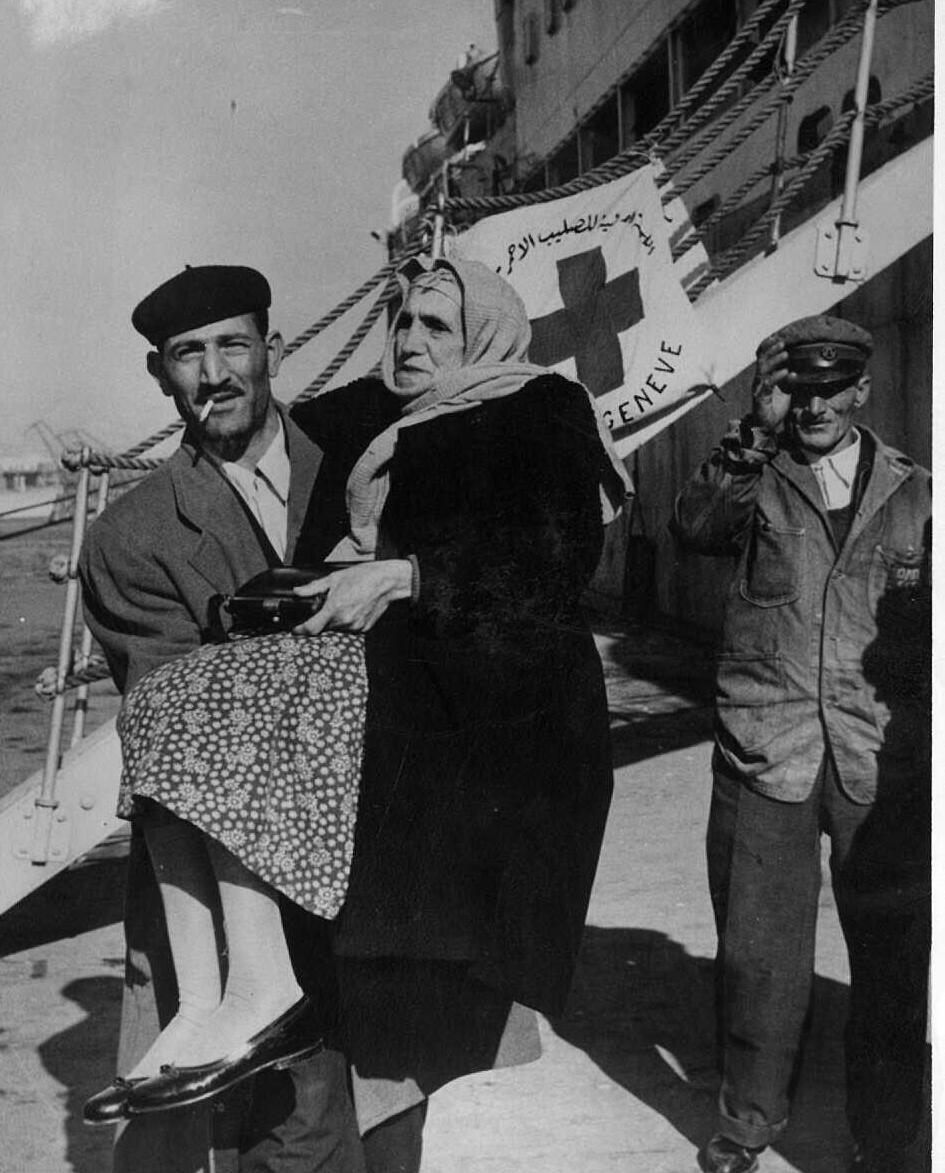

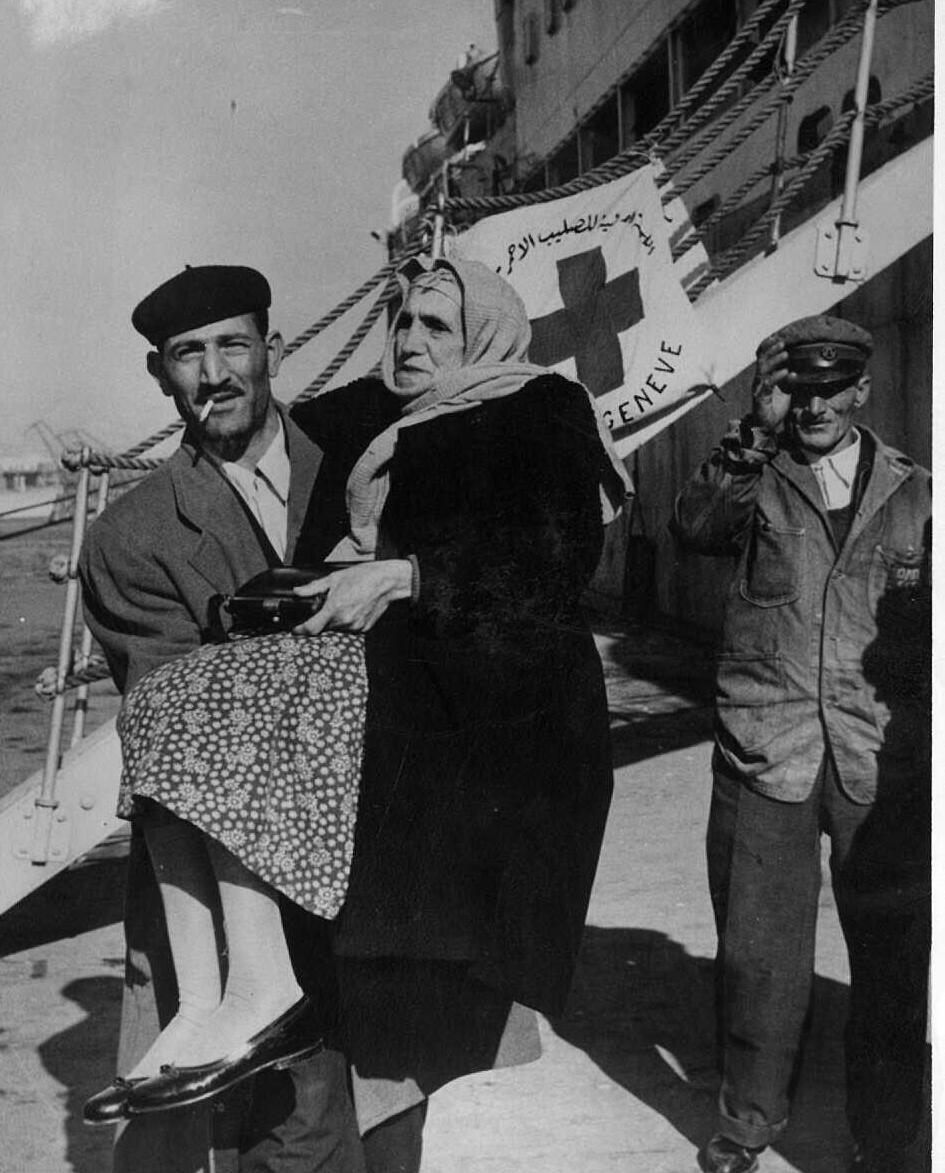

The sounds of Piraeus

Some 30,000 Jews were forced to leave Egypt following the persecution. Many escaped on Red Cross-chartered ships to Athens, Naples and Marseille. In February 1957, a poignant image captured a Jewish refugee in Piraeus, Greece, carrying his elderly mother from a ship as they journeyed to Israel. Only about 3,000 Jews remained in Egypt.

15 View gallery

A Jewish refugee from Egypt carries his elderly mother down the gangway at Piraeus port, 1957

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

Meeting with President Ben-Zvi

The Jewish refugees who fled to Israel were determined to maintain their community life. In April 1957, Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who had a deep affinity for Egypt from his time in the Zion Mule Corps and previous encounters with the local Jewish community, met with their representatives. Although the refugees realized that while the president's sympathy was genuine, it did little beyond offering empathy.

15 View gallery

Refugees from Egypt meeting with President Ben-Zvi in Israel, 1957

(Photo: The Zionist Archive of the World Zionist Organization)

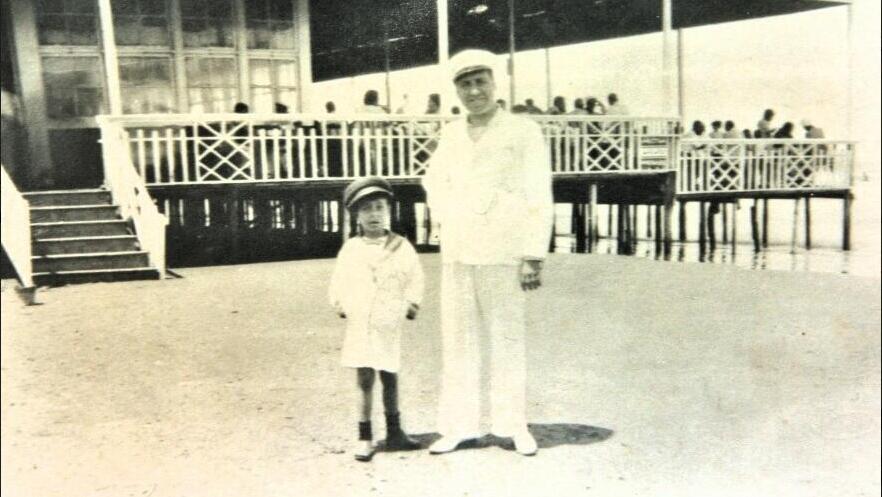

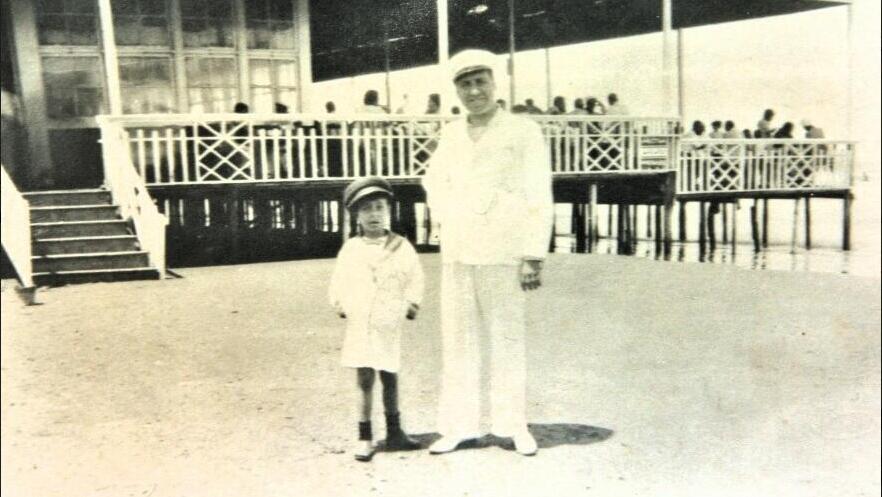

A little piece of heaven

For those wondering how many Egyptian Jews found it difficult to leave, Zamir describes a scene featuring her father, Victor Vidal, and her older brother David, against the backdrop of the lovely Casino Fouad in Ras El Bar, near the ancient port city of Damietta, nestled between the Mediterranean Sea and the Nile River.

15 View gallery

Victor Vidal and his son David in the resort town of Ras El Bar

(Photo: Courtesy of Levana Zamir)

"Wealthy Jews from Cairo used to spend two summer months in Ras El Bar to escape Cairo's stifling heat," she explains.

"Families arrived with their children and two maids, living in spacious, airy bamboo villas. Mornings were spent by the sea, and evenings along the Nile with dances at riverside hotels or night-time sailing on Nile sailboats. It was a little piece of heaven."

Peace with Egypt, but no Jews

On June 5, 1967, the Six-Day War erupted, and on that same day, Egypt arrested roughly 500 people, nearly all the country’s remaining Jewish men.

15 View gallery

Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat shaking hands - the first peace agreement between an Arab state and Israel

(Photo: GPO)

They faced torture, some were expelled, and others were unable to leave the country, even if they wished. By 1968, only about 2,000 Jews remained in Egypt, and in 1971, when the Egyptian president permitted Jews to leave, nearly all seized the opportunity.

Post-1971, few Jews remained in Egypt, and those who did, lived in fear, especially after Egypt and Syria attacked Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

However, just four years later, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat stunned the world by visiting Israel, subsequently signing the first peace agreement between an Arab state and Israel.

As part of the agreement, Israelis were allowed to visit Egypt, but the remaining Jews in Egypt sensed they were unwelcome. By 1996, fewer than a hundred Jews remained in the country.

Take me back to Egypt

In early 2020, just before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Levana Zamir returned to her birthplace in Egypt, accompanied by her daughters and grandchildren, 70 years after her family was expelled. They had spent about six months in a transit camp in Marseille before moving to an immigrant absorption camp in Israel.

In an interview with Ynet, Zamir shared that the most emotional moment of the trip occurred in Cairo when her grandson, Caesar, was invited to blow the shofar at the Shaar Hashamayim Synagogue, where his grandfather, Caesar (Ezra), after whom he was named, once prayed.

"When I saw him blowing the shofar in the place where his grandfather had prayed, I cried. The tears just flowed. I said, 'Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who has granted us life, sustained us and enabled us to reach this occasion,’" she recounted. Last year, only three Jews remained in Egypt.

(Photo: Courtesy of the International Organization of Jews from Egypt, Levana Zamir, the Zionist Archive)

"The Jewish community in Egypt has a long history of 3,000 years of vibrant life, rich Jewish culture and heritage,” said Dror Morag, a member of the executive of the World Zionist Organization and head of its Social Involvement and Tikkun Olam department.

“It has had its ebbs and flows, days of prosperity alongside periods of severe persecution. Over the years, and since the establishment of Israel, the community has dwindled. On the eve of Passover, which commemorates the Exodus from Egypt, we remember the community that once was and proudly reflect on the realization of the Jewish and Zionist dream – the immigration and settlement in the State of Israel."

First published: 13:36, 04.22.24