Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The sirens that pierced the skies of the country on Yom Kippur, in October 1973 sent hundreds of thousands of soldiers into a sudden state of war. At a time when the means of communication with the front were limited, many families did not know for a long time what happened to their loved ones. Even the army did not know how to deal with the number of prisoners and soldiers missing in action - those fighters whose fate was unknown, even to their commanders.

More stories:

More than a thousand soldiers were declared MIA at the end of the war, it is not known what happened to them, during the fighting the number was much higher. The acute demand from the families required the army to recalculate its course. Gathering information from the foreign media, aerial photographs of the tanks and outposts that were hit, or bits of information from shepherds or random passers-by. The army worked around the clock to locate those missing. To this day, 50 years after the war, efforts to locate the 16 whose burial place is unknown are still ongoing.

Census just before the war

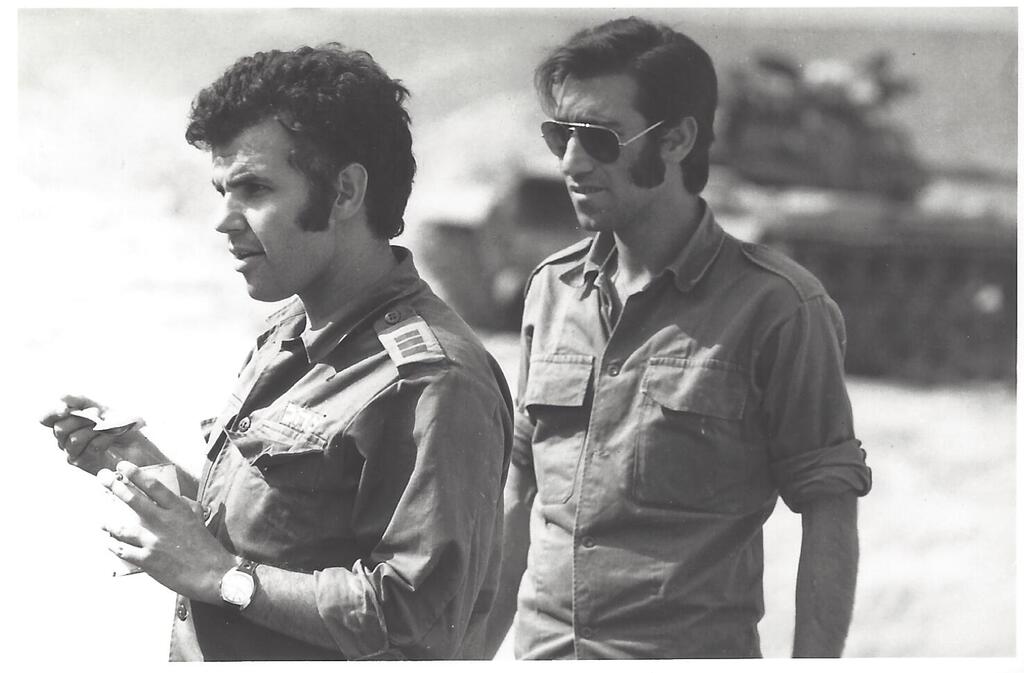

Hanan Goral was among the first to recognize the need to establish a unit to locate MIAs. At the beginning of September 1973, Goral, who was then an adjutancy officer of the 68th Battalion, was called to reserve service. "There was a feeling that something was going to happen," he says.

When the troops mobilized before Yom Kippur to reinforce the outposts in the Suez Canal, Goral made a decision that to this day he cannot explain. He convinced the deputy battalion commander to move between the outposts and do a kind of population census. "Until midnight, also a little out of the boredom of the fast, we prepared a big board with the names of the people."

The war broke out and the outposts where the soldiers of the regiment were stationed were under heavy fire from the Egyptians. 48 hours after the attacks began, the fighters were sent to the area of Jerusalem to hold a line on the border with Jordan. "At this point in time, I'm missing 120 people that I don't know where they are," Goral says. "I made a decision that I will not go with the forces but will open a war room in the battalion's offices and try to give answers to the families."

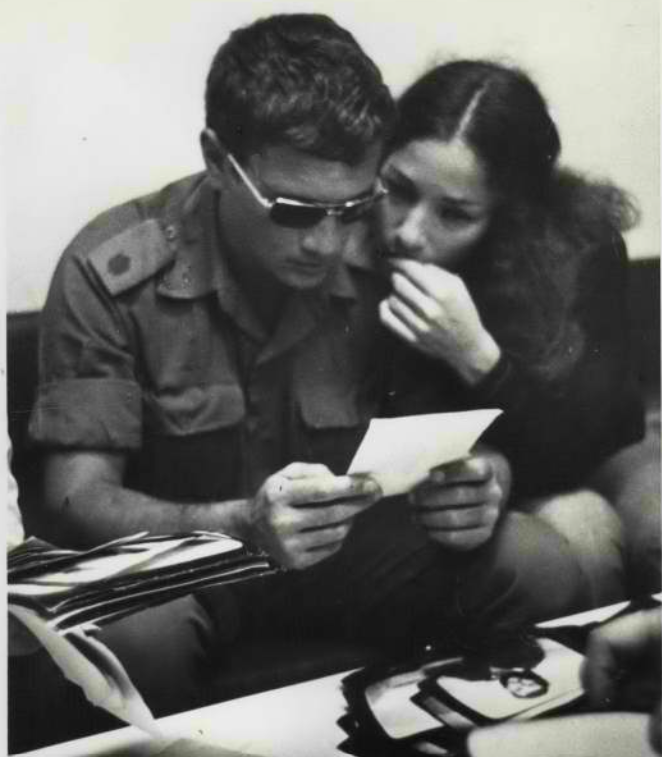

"After one day I realized that this was not a simple operation," he said. "I recruited two television crew members from the foreign press and two photographers and we set up a model of a missing persons identification center. We received film clips from all the foreign networks with photographs of prisoners. Some were listening to the orders shouted by the Egyptians and raised their heads to the camera when asked, and some hid their faces. We cursed the latter because the faces we saw were able to identify and update the Red Cross."

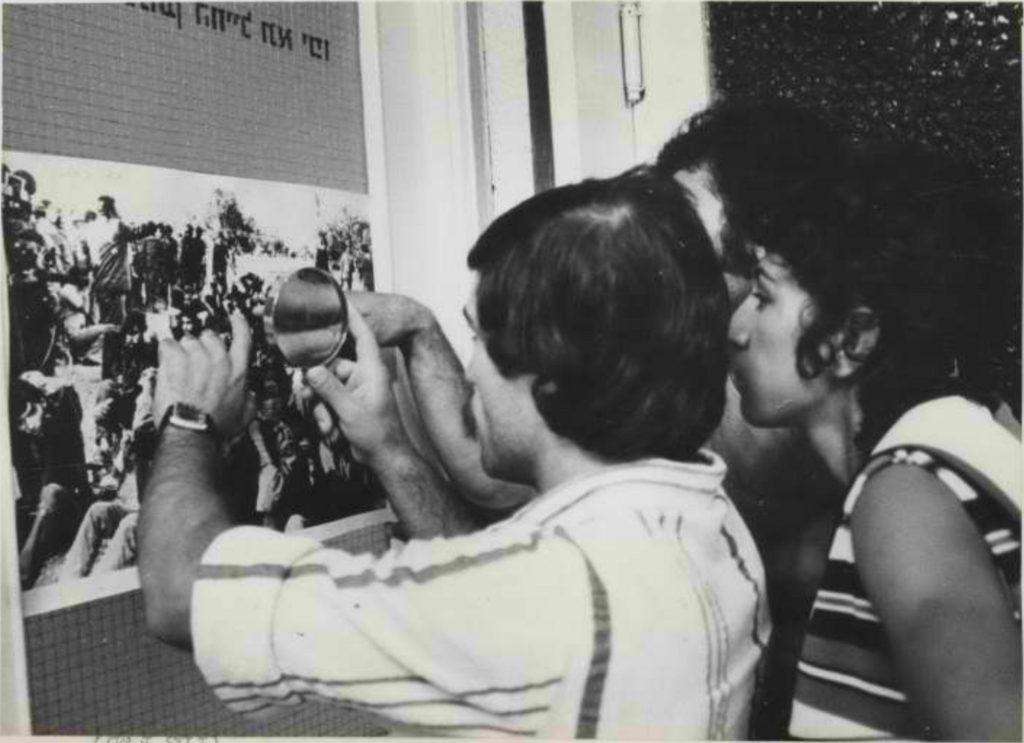

After a month during which Goral and his men were the only ones engaged in locating the MIA's, the IDF established a main center in Tel Aviv, based on Goral's model. It was the "basement of tears" - the place where the families of the missing flocked to watch filmed reports from the foreign media in the hope of finding a slither of information about their loved ones, and quite a few tears fell in those rooms.

Goral was not satisfied with information from the foreign media and began questioning the fighters who had been in the outposts when the fighting began, about the fate of their comrades. At the same time, he recruited Nechama de Shalit, manager of a psychological treatment department, who, together with the therapists she recruited under her, provided answers to the worried families. "We had to give the families emotional support because they came non-stop. When we knew about anyone who was not alive, we immediately informed the families. It was a very difficult job."

"The families fought against the office, which did not withstand the pressure"

The "basement of tears" provided an initial response to the families, but the number of missing soldiers was very high and the IDF was required to address the issue in a broader way. "During the Yom Kippur War, the situation was chaotic. There were a lot of casualties, but a situation arose where the families didn't really have where to turn to for answers and they relied on an office in Tel Aviv that could not withstand the pressure," Col. Ret. Dvora Tomer, who ran the family contact center says.

"I was waiting to start my university studies when I was offered to take on the task,". Tomer says. "I started with a secretary and two soldiers, and we grew to a group of 40 people - military personnel, reservists, volunteers, even women from the British army. In addition, we were supported by staff members such as a psychologist, an identification expert, a rabbi for questions from religious families."

Her team gathered the information from all possible sources and centers in the IDF, and in fact, became the address of the families. "Each family that came to us sat in front of an interviewer who took down their information and then attempted to find answers for them. Often members of those families then joined us as volunteers to help others," she says.

"We had a case where a father recognized his son's shoes in photos of prisoners. Our identification expert verified this, and that's how we actually managed to confirm that his son was alive," she says. But along with the successes, there were also unbearably difficult moments of crying and screaming from the fathers and the mothers. During the day we worked and at night we cried. We had a room where we, the staff members, could go to after a meeting with a family, to cry, have a hot drink, or father strength for the next meeting."

The first search expeditions

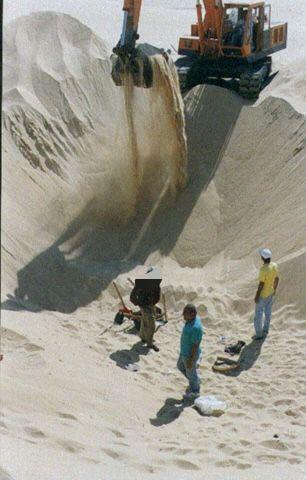

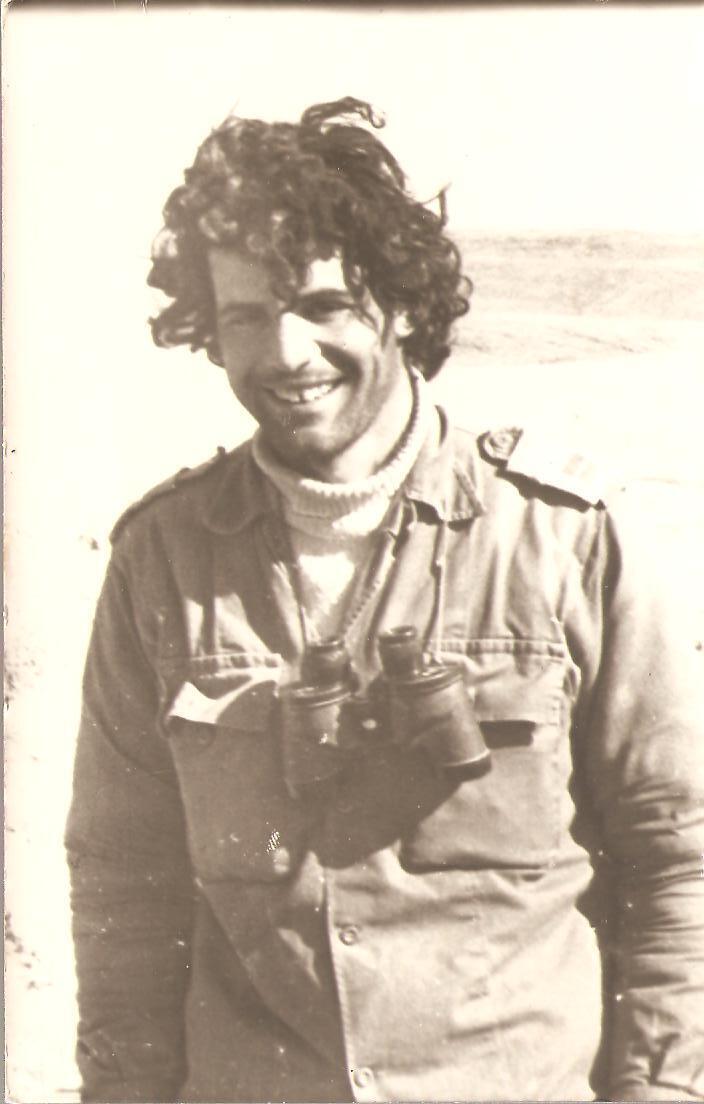

After the end of the war, the IDF began sending out search expeditions for the hundreds of fighters who were declared missing in the battles against the Egyptians in Sinai. Dr. Chaim Rubinstein, then a reserve fighter in the armored corps who participated in those battles, decided to join the expeditions. I knew there were still a few months until the school year started and I immediately agreed."

It was a bereaved father who prompted the military to launch the expeditions. "Col. Avraham Eilon's son was an artillery officer who was killed in the Golan Heights. When the war ended, he went up to Mount Hermon and together with soldiers from the Golani brigade and a POW interrogator, they found the son's body under a pile of stones. After the funeral, he went to the Chief of Staff and said that they must start organizing a search for all the MIAs," Rubinstein says.

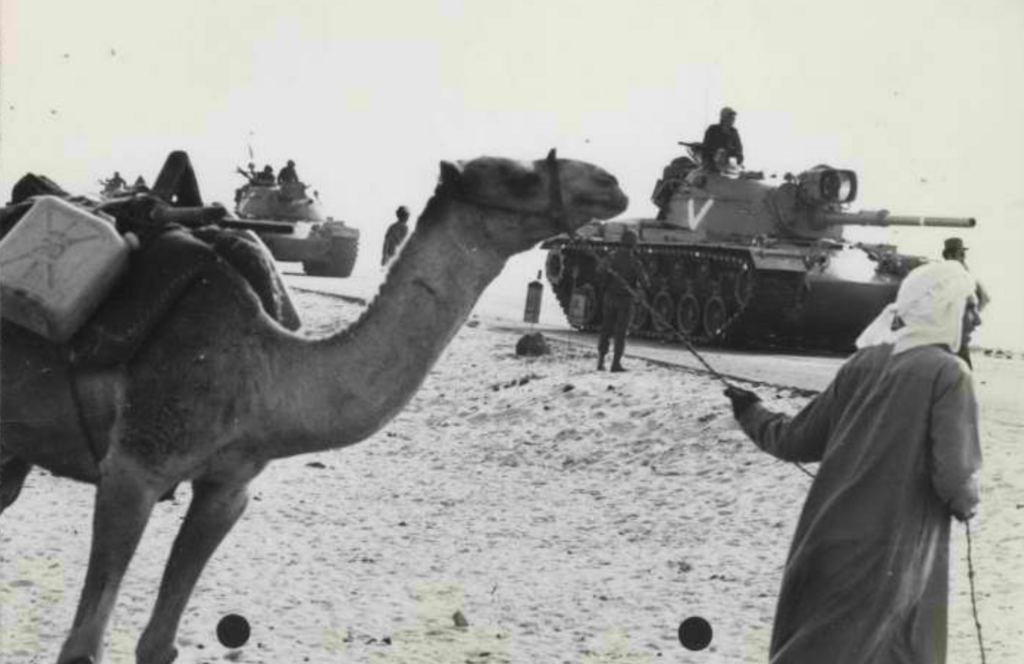

The initial number of MIAS was over one thousand. "Many had moved from tanks that were hit or separated from their original units in the fighting, making it more difficult to locate them and confirm whether they were in fact missing. In the South, vast parts of the Sinai where fighting had taken place, were occupied by the Egyptian army," he says.

The Israeli search teams had a map shared with the Egyptians, on which they marked the places where they believed there were missing persons. "We studied how the battles were conducted. There were also aerial photographs that showed us where tanks were stuck. We compiled records, that were passed on to the joint search committee - the Egyptians would approve them and we would come to the cease-fire line, where the UN representatives were waiting. The Egyptians did not allow us to freely patrol the area, so they would put us in a closed truck and direct us straight to the point they had marked so that we would not see their preparations," Rubinstein says.

"We would get to the tank, for example, and there we were allowed to search about 500 meters around the vehicle. There were missing people who were inside the tank and there were some who were outside but were hit by gunfire or shrapnel. The Egyptian army almost always buried the missing near the tank."

"As long as there is no grave, there is a chance that he will return"

The searches did not stop for a moment. Within a year of the start of the searches, the number of MIAs dropped to a few dozen. Rubinstein, who started out as a volunteer, was one of the first in the army's EITAN (Tracing Missing Persons) unit, and later was also responsible for investigating MIA'sfrom the Egyptian front

After the signing of the peace agreement with Egypt, and as the searches continued, better conditions were created for searches and against all odds, bodies of soldiers were found even more than 20 years after they fell in battle. Thus, for example, the body of the late pilot Eran Cohen was brought to burial 22 years after he died, and the bodies of Leon Cohen and Nadiv Mordechai, two members of a tank crew who were killed on the first day of the war, were brought to burial 26 years later.

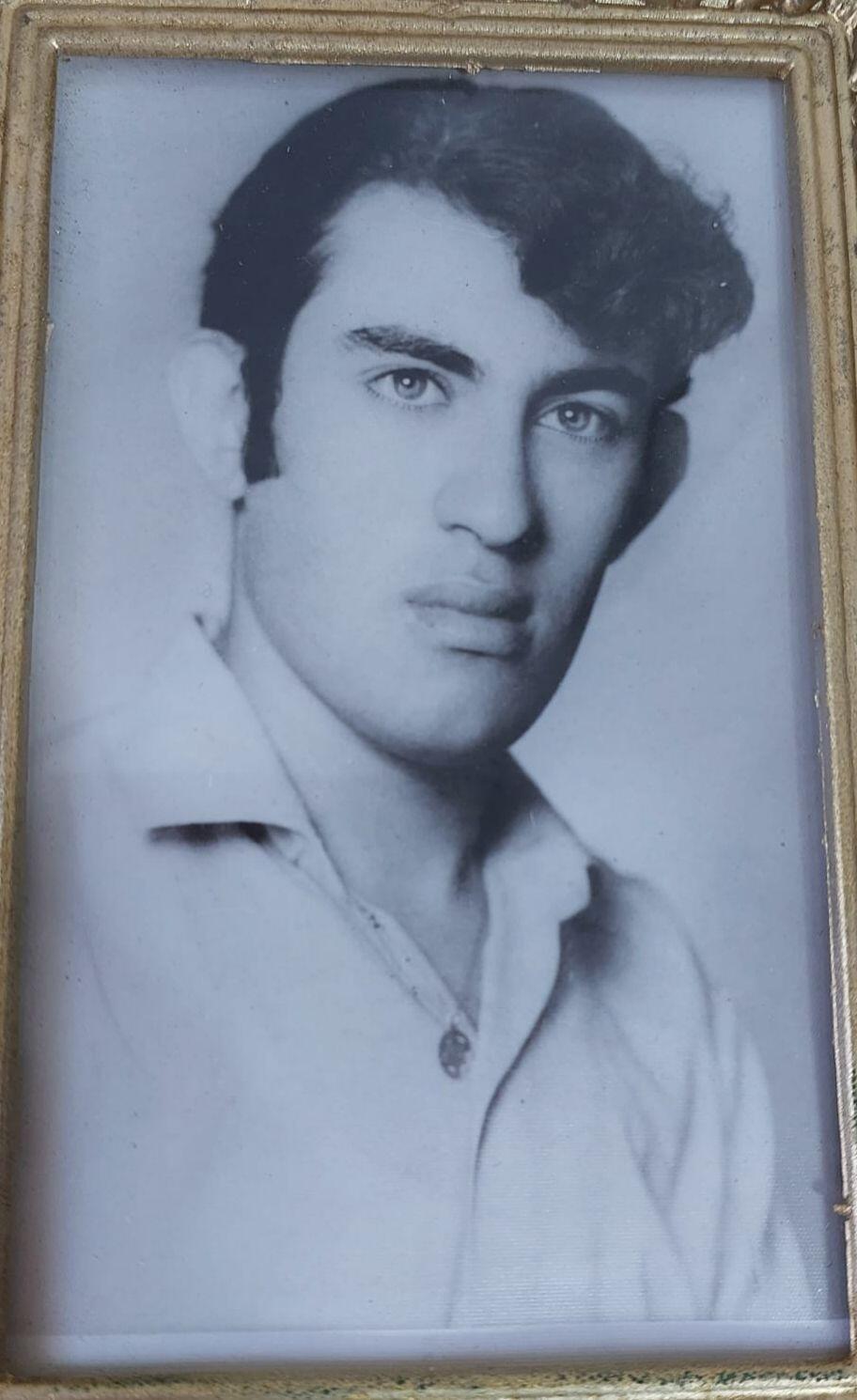

Ruth Mordechai still remembers the hope and expectation that her older brother Nadiv would return home. "I was eight years old when I arrived home with my brothers to my father screaming. My aunt took us away immediately and did not allow us to enter the house. I realized that something terrible had happened but was not told what it was. When we returned home three days later we only gathered bits of information. They said Nadir could not be found. It was a very freighting thing to think about."

Three years after he disappeared, Nadiv was declared a casualty of war whose burial place was unknown. "We had hoped that he was alive. We went over to the neighbors to watch the prisoners return on their television because we didn't have one. My oldest brother, who was a soldier himself, went physically to search for Nadir in hospitals. It was difficult. We only had the care of our parents who managed to keep us together even during the difficult days of the crisis," she says.

"Even after he was pronounced dead, hope did not fade. As long as there is no grave - there is a chance that he will return alive," she says. "Every little thing we wanted to do were postponed because maybe my brother would come back. I remember my sister wanted to travel and canceled her trip because she wanted to be in Israel when Nadiv was found."

Ruth's father died before her brother's body was found. "He was a bereaved brother and in those years he did not believe that he was also a bereaved father. He always said that Nadiv was not killed, and with this belief, he died." After Nadiv's body was found and he was brought buried, the family had some peace. "It healed the family. Now there is a place to come, an address. It has become a place where we can talk, put flowers, cry."

In the family of Leon Cohen, who served and fell together with Nadiv, the feelings are similar. After his parents heard that Leon was missing, the family fell apart. "The parents were deeply saddened and did not accept the news. We did not understand at all what it means to be missing," says sister Esther Hayun.

Even after he was declared a casualty whose burial place was unknown, my mother did not lose hope and dreamed that one day he would knock on the door."

"My husband and I, who were just friends at the time, went to the military HQ to try and identify him among prisoners, and there was hope that he was among the living," she says. "Little by little, since he was not among the captives, grief took over. Even after he was declared a casualty whose burial place was unknown, my mother did not lose hope and dreamed that one day he would knock on the door."

And yet, the parents refused to cooperate with the military authorities thinking that the son might still be alive. "Over the years, I participated in the memorial services, and my parents also came. The memorial services were accompanied by the heartbreaking cries of mothers whose sons went to the army and never returned. The crying caused my mother to go blind over the years, my father died of grief, and my younger brothers were not cared for properly and were emotionally damaged. They did not marry and my mother kept them close and did not let them experience life. Of course, they didn't serve in the army either."

26 years after the war, the news that Leon was found was unexpected. "The military contacted us and asked to do DNA tests. They didn't explain why. A few months later they called the whole family, including grandchildren, to announce that Leon had been found. My first reaction, like my mother's was, 'Is he alive?' This discovery opened the wound again, but at the same time, gave closure after years of expectation and questions. Finally, we had a grave to cry and mourn over," Esther says. "This is an enormous pain that left a mark on the whole family, including my own children who grew up in the shadow of bereavement."

"They believe there is still a chance to find missing bodies"

"There are several cases that we still have not been able to locate and there is no doubt that this is something that goes with me," said Rubinstein. "The most famous of them is Capt. Miron Eltegar and his tank crew."

"We investigated it a lot and even met someone who claimed to have cremated the bodies, and he brought us to an alleged location in the heart of Port Said, but we were unable to locate anything," Rubinstein says. "I would be happy if we could find all of the missing. I know how much peace it brings to families. When locating missing persons, these are happy funerals."

Meanwhile, the IDF continues to search for the missing people from the Yom Kippur war in Sinai. "Even after 50 years, the IDF continues to invest resources in the search for the remains of the missing," an officer in the Eitan unit says. "It is impossible to estimate the chances of finding missing bodies, but we believe there is a chance, otherwise we would not have invested so much effort. We will not stop until we find all of them."

"For the families, of course, this is an open wound, and they expect closure even after 50 years. They have not lost hope that their loved ones will be brought to a grave in Israel," the officer says. "Our duty is to return them to Israel. When we deal with this very important and sensitive matter, what stands before our eyes are the families who are waiting and those soldiers whom we had sent to battle and have not yet returned."