Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Generations of Israelis have been raised on the narrative of oppression by the Ashkenazi-Sabra establishment toward the underprivileged Moroccan community, from Sallah Shabati to Kazablan, the Black Panthers, the Wadi Salib riots and the political rise of Aryeh Deri.

Stories of the North African community, grateful for the refuge provided by the new Israeli state but subjected to humiliation, racism and disdain, have shaped Israel’s cultural, social and political landscape.

6 View gallery

Boulevard Antéo in the international city of Tangier, 1950

(Photo: Center for Jewish-Moroccan Culture in Brussels, courtesy of Paul DeHaan)

However, this narrative, while not entirely false, is only part of the picture. The story of Moroccan Jewish immigration is far more complex, as revealed by historian Dr. Aviad Moreno.

"Members of the Moroccan-Spanish community had ties to multiple homelands," Moreno frequently emphasizes, "not just to Morocco and Israel."

What does "Spanish Morocco" refer to? A bit of history: After the expulsion from Spain in 1492, many Jews sought refuge in Morocco. About 420 years later, Spain occupied northern Morocco, creating a "Spanish Protectorate" that included cities like Tetouan, the capital of Spanish Morocco, and Larache and Alcazarquivir. The nearby city of Tangier became an international zone in 1924, while the rest of Morocco became a French protectorate under a 1912 treaty. The Spanish-ruled region was commonly known as "Spanish Morocco," and its Jewish population, about 12% of Moroccan Jews, numbered 30,000 out of a total of 250,000 in the 1950s.

This group, the focus of Moreno’s new book, did not solely identify with their Moroccan homeland or Israel, as commonly taught in schools when discussing the mass migrations of the 1950s and 1960s. Instead, as Moreno reveals, they embarked on fascinating migration journeys years earlier, spanning three continents.

In addition to Israel, Jews from Spanish Morocco migrated to the Iberian Peninsula—Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar—and to South America, including Brazil, Peru, Argentina and Venezuela, where they continued to embrace Spanish culture.

Which period are we talking about?

"From the early 19th century to the mid-20th century, covering about 150 years. The earliest migrants were Jews from northern Morocco. By the early 20th century, some had even returned to Morocco, which they still viewed as their homeland."

Why is this significant?

"The Jews of Spanish Morocco didn’t see themselves as a weak group simply looking for escape routes out of Morocco. When they or their descendants returned to northern Morocco, they continued to long for South America. In fact, Jewish newspapers in Spanish Morocco printed congratulatory messages for Peru’s Independence Day and featured ads for Jewish stores named after Venezuelan cities. This was a migration that wasn’t one-way."

Moreno further explains that, in contrast to the stereotype of French-speaking Moroccans as "fake Frenchmen" (a term coined as "Frenchechocs"), the Moroccan-Spanish community sought to present themselves as carriers of a more authentic Spanish culture, dating back to pre-1492 Spain. This unique culture included their own language, Hakitia, a blend of Spanish, Arabic and Hebrew.

From Venezuela to Be'er Sheva

Moreno leads a research group on migration at the Ben-Gurion Institute at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. His focus on Spanish Morocco is no coincidence. "I’m of Moroccan descent, and my grandfather, Alberto Moreno, traveled to Venezuela to teach Hebrew at the Herzl-Bialik School. My father later immigrated to Israel and settled in Be'er Sheva."

In the southern Israeli city of the 1980s, before the wave of immigration from the former Soviet Union, most of Moreno’s neighbors and friends were of Moroccan descent. "Some called me ‘the Ashkenazi Moroccan’ because my father had come from Venezuela," he recalls.

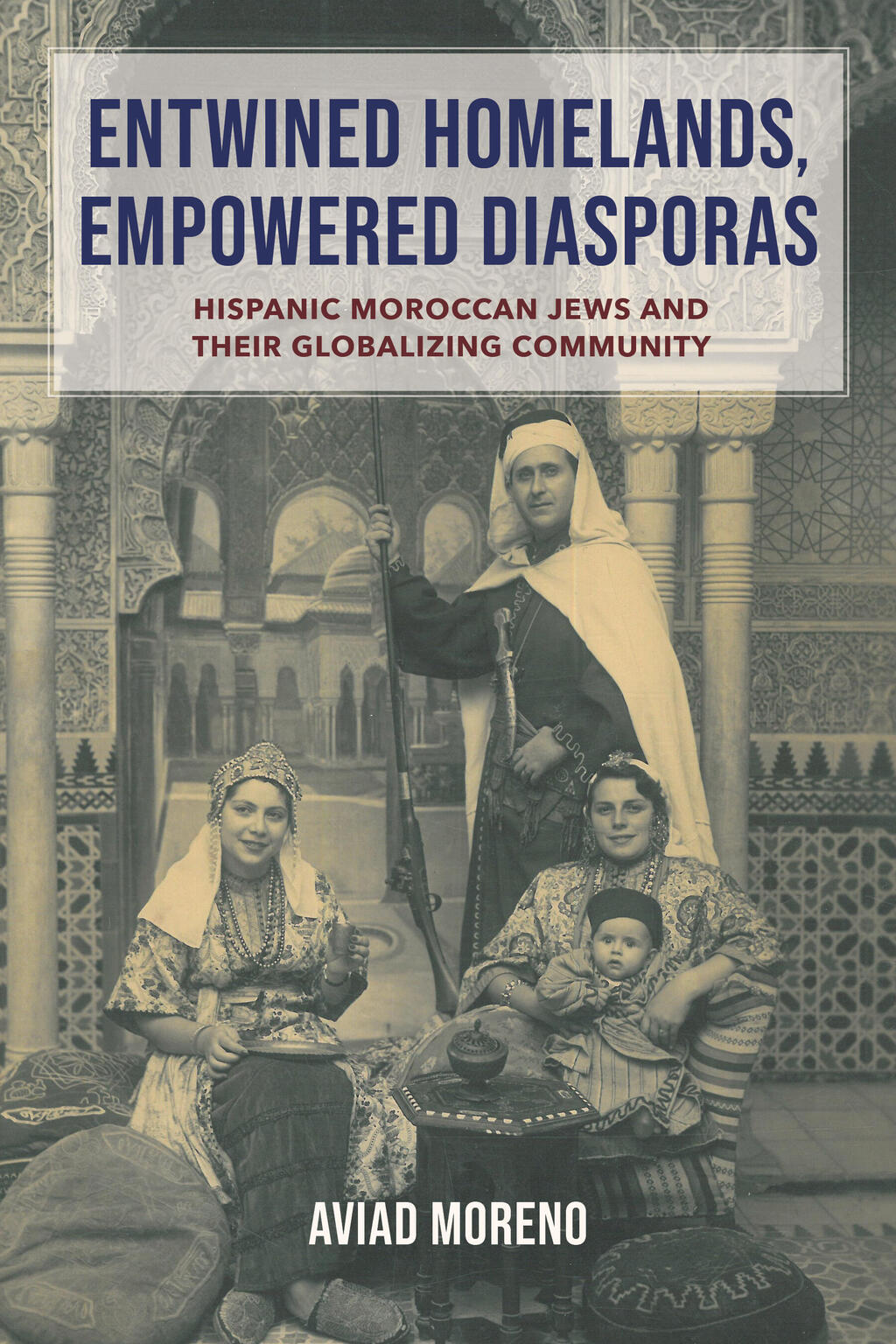

The cover of Moreno’s book, Entwined Homelands, Empowered Diasporas (Indiana University Press), features a photo of his grandparents with his aunt and father, who was an infant at the time. The picture was taken on their way to Venezuela. It was a hot day, and they stumbled upon a tourist booth with medieval costumes. They dressed up and took the photo.

"As a child, I naively thought it reflected their way of life in Morocco," Moreno admits, explaining his choice of the photo to illustrate the interplay between modernity and tradition.

The story of the Moreno family dates back over 200 years. Spanish-Moroccan Jews migrated to Gibraltar, where they established a community that remains active today. Others ventured as far as Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela.

"The first female doctor in Venezuela was a Jewish woman, a descendant of North Moroccan immigrants," Moreno notes. Similarly, David Levy Yulee, the first Jewish U.S. senator, was the son of a Jewish merchant from Morocco.

When Spanish soldiers arrived in northern Morocco during a brief conquest in 1859, they were surprised to encounter a native community that spoke a language closely resembling their own.

In the 20th century, Spanish cultural influence deeply permeated the Jewish community, following the Spanish occupation that lasted until 1956. Spanish became the dominant language in the north. This encounter not only spurred interaction between Spanish culture and northern Moroccan Jews but also sparked a movement among Christian Spaniards seeking to bring Sephardic Jews back to Spain.

However, the Spanish influence had mixed effects on the local Jewish community. While it introduced modernity, it also led to secularization and a drift from tradition, as seen in the incorporation of Spanish-style seafood into meals.

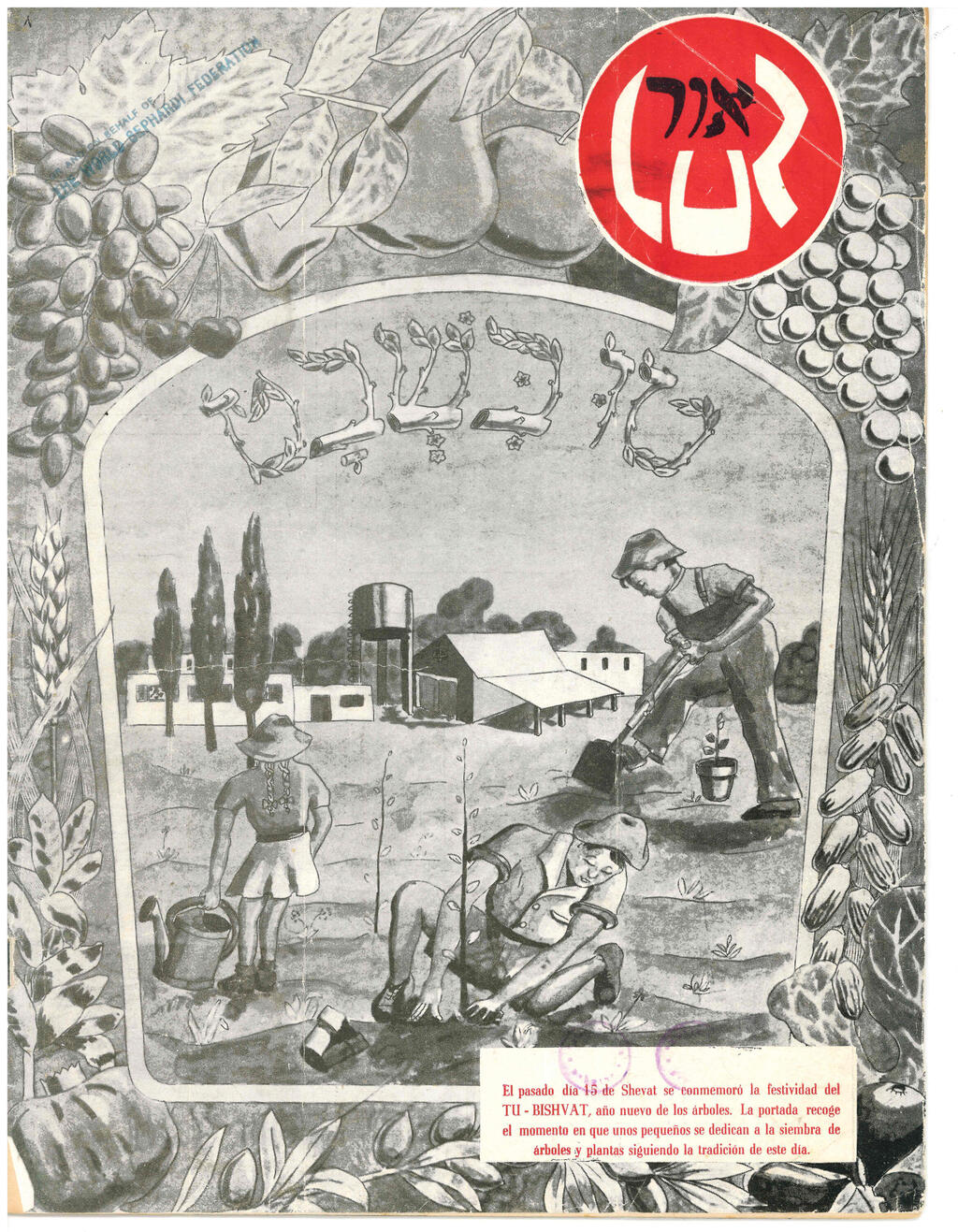

"In one Jewish newspaper, Or, I came across an ad printed with inverted letters. I initially thought it was a printing error," Moreno says. "It turned out to be an ad for a restaurant specializing in a well-known Spanish dish made with shrimp."

Amid this cultural blending, some voices within the community called for a boundary to be drawn, advocating for a return to Jewish tradition in Spain, and expressing concern over the community's embrace of Spanish customs.

Spanish Jews and Zionism

We've learned about the Moroccan-Spanish Jewish community with its "multiple homeland ties," but does this connection to Spain mean a lack of Zionist elements? Dr. Moreno’s research suggests the opposite.

Zionism, he explains, arrived in Morocco in 1900, just a few years after the First Zionist Congress. The first two Zionist societies in Morocco were Shaarei Zion in the southern port city of Mogador and Shivat Zion in Tetouan, part of Spanish Morocco. The latter was founded by Rabbi Yehuda Leon Kalphon, a proponent of the movement to reconnect with Spain, and Dr. Berlievevsky, a Russian Jewish doctor who had immigrated to Morocco after training in France.

Did their connection to Spanish culture weaken their Zionist ties?

"On the contrary," says Moreno. "There’s a very clear correlation between the desire to reconnect with Spanish culture and the embrace of Zionism among most Zionist pioneers in northern Morocco. Think of the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry in the early centuries of the last millennium, and the movement to restore Jewish cultural pride in Spain—doesn’t that provide a solid foundation for the ideals of political and spiritual Zionism?"

Interestingly, while France feared that Zionism would erode the "Frenchness" of Moroccan Jews, Spain was not similarly alarmed. The Spanish believed that their culture was so ingrained in the Moroccan-Spanish Jews that it would endure, even alongside the rise of Zionism.

One fascinating example of the Zionist efforts of Moroccan-Spanish Jews can be found in South America. The first Eastern European Jewish immigrants to South America brought Zionist ideas with them, but the Moroccan-Spanish Jews struggled to integrate, primarily because everything was conducted in Yiddish—a language they didn’t know.

But they didn’t give up. In 1917, following the Balfour Declaration, Yaakov and Shmuel Levy, immigrants from Spanish Morocco, founded Israel, the first Zionist newspaper in Buenos Aires, written in Spanish.

In Brazil, David José Perez, an immigrant from Tangier, founded Columna A, the first Zionist newspaper published in Portuguese, together with a non-Jewish partner sympathetic to Zionist ideals. Many of the Zionist pioneers in Morocco were returnees from South America.

In Tangier, several Spanish-language newspapers with a distinctly Zionist tone emerged in the following decades, including one that dedicated a special issue to Herzl, funded by the Spanish government.

Did this connection to Zionism persist after the establishment of Israel?

"In Tangier, for example, many Jews didn’t emigrate to Israel but remained deeply connected to Zionism. They expressed their concern for Israel in unique ways. In 1956, for instance, the Spanish flag was raised in Israel for the first time during an event organized by activists from northern Morocco, aimed at strengthening cultural ties between Israel and Spain."

Morocco gained independence in 1956, and 30 years later, in 1986, Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres visited Morocco, meeting King Hassan II in the resort town of Ifrane. This visit paved the way for Israelis to travel to Morocco. "Intriguingly, that same year, Israel and Spain established formal diplomatic relations," notes Moreno. "This allowed Moroccan-Spanish Jews to visit both of their homelands."

Moroccan-Jewish culture remains distinct in Israel, even in the 21st century. Literature, cinema, cuisine and politics have not eroded the unique heritage of Moroccan immigrants. Alongside this recognition, Moreno and other academics in the field hope that the unique language, culture and contributions of Moroccan-Spanish Jews to Israel’s cultural diversity will not be forgotten.