Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In July 2024, Iranian-born economists Mohammad-Reza Farzanegan and Nader Habibi, who reside and conduct research in the West, published a study examining the impact of economic sanctions on the size of Iran’s middle class.

The study, recently translated into Persian by the Tehran Chamber of Commerce, has been widely reported in Iranian media as evidence of the harmful effects of the economic sanctions imposed on the country.

According to the study’s findings, Iran’s middle class shrank by a staggering 88% between 2012 and 2019, an average annual decline of 11%, due to Western sanctions. The sanctions led to a slowdown in economic growth, the collapse of numerous private companies and a sharp rise in inflation, which in turn resulted in a 28% decrease in the average real annual income in Iran.

The findings are not surprising, given the severe economic crisis that has gripped Iran over the past decade, heavily impacting the middle class. While the economic crisis has affected the entire population, the middle class has borne the brunt of the hardships. The upper classes have generally been able to withstand the economic downturn, and the lower classes have received partial compensation from the government in the form of subsidies and basic imported goods. However, the middle class has largely shouldered the economic burden.

Resistance economy

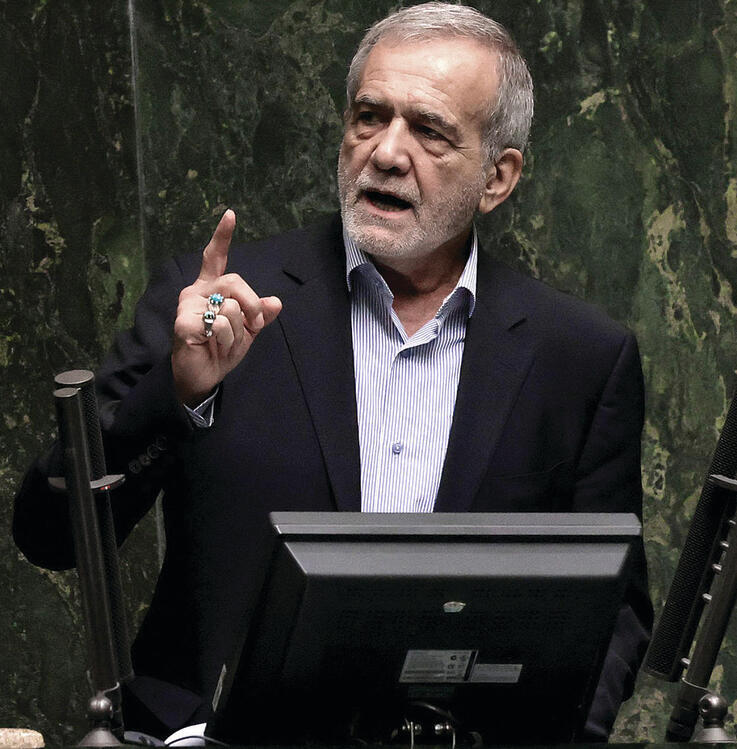

Some observers view these findings as an encouraging sign that the economic sanctions are effectively pressuring Iran’s economy, potentially forcing the Tehran regime to soften its stance and agree to renewed negotiations with the West over its nuclear program. This perspective is further bolstered by the new Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian’s promises to pursue renewed dialogue with the West in an effort to lift the sanctions.

However, this approach contrasts with the views of conservative and radical factions, led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who believe that the key to improving Iran’s economy does not necessarily lie in lifting the sanctions. Instead, they advocate for adapting the economy to the conditions imposed by the sanctions through a “resistance economy,” which emphasizes increased self-reliance and reducing economic dependency on the West by diversifying income sources and economic markets.

Moreover, the ongoing erosion of Iran’s middle class carries negative implications for the prospects of political change in the country. In recent decades, there has been a growing divide between the Iranian regime and the younger generations, particularly the second and third generations of the revolution, who are increasingly distancing themselves from revolutionary values. This trend is most evident among the middle class, which has greater exposure to Western culture.

The central role of the middle class in the 2009 Green Movement and the wave of protests that erupted in September 2022 following the death of Iranian woman Mahsa Amini underscores this dynamic.

Political commentator and regime critic Sadegh Zibakalam highlighted the central role of the urban middle class in these protests during a recent interview, noting the relative calm that prevailed in areas predominantly inhabited by lower-income groups, including in Tehran itself.

In recent decades, there has been a growing divide between the Iranian regime and the younger generations, particularly the second and third generations of the revolution, who are increasingly distancing themselves from revolutionary values.

In contrast to the central role traditionally played by Iran’s urban middle class in movements for political and social change, recent waves of protests—particularly the fuel riots in late 2019—have been largely led by the country’s marginalized populations, who are struggling with severe economic hardships.

The middle class, typically seen as the backbone of such movements, has largely remained outside the circle of protest. According to Iran’s Intelligence Ministry, the majority of those arrested during the fuel riots were unemployed, low-wage workers or individuals with low educational attainment.

In recent years, the worsening economic and social crises have pushed the fight for political and civil liberties down the public agenda in Iran. The deepening economic crisis has forced citizens, including those in the middle class, to focus on daily survival, leaving little room to engage in the struggle for freedom.

Iranian economist Mousa Ghaninejad commented on this phenomenon, saying that the economic improvements of the 1990s allowed the middle class to demand political rights. He argued that citizens primarily concerned with improving their economic situation are less likely to engage in the pursuit of political freedoms.