As olive harvest season begins, the Israeli olive oil industry faces significant challenges. Farmers in the north had hoped that by harvest time, the threat of cross-border fire from Lebanon would have receded, but that hasn’t happened. Harvest workers are forced to contend with ongoing risks in open fields, leaving many olives unpicked and at risk of becoming bitter and unusable.

“I know coming here is like playing Russian roulette, but what can I do? These are trees I planted in 1988—this is our heritage,” said Roni Bahmutski, who owns an olive grove near Metula on the Lebanese border.

Last year, Bahmutski lost over 90% of his crop, unable to access his trees or hire workers to pick the fruit. This year, he’s gathering olives by himself, trying to salvage what he can. "So far, the government hasn’t settled compensation for our 2023 losses. For some reason, olives were excluded from other fruit crop compensations," he added, noting that aside from an advance payment covering part of his lost revenue, he has received no other support. Nearly 16 tons of olives went to waste.

Tragedy struck last week when, just minutes after a heavy barrage on Metula, Bahmutski learned that his friend’s son, Omer Weinstein, had been killed with four workers in an apple orchard nearby. Despite the heartbreak and personal danger, Bahmutski continues working in his grove, even as he struggles to find laborers willing to help.

“When I heard Omer was gone, I cried like a child. He was family to us,” he shared. “My home in Metula was hit too—windows and shutters shattered, the yard destroyed. We farmers risk our lives just stepping into our fields, but this is my livelihood and life’s work. My family and friends ask why I keep going, but I can’t let everything just fall apart.”

Two weeks ago, eight farmers were killed while working in fields, orchards and groves unprotected from rocket fire out of Lebanon. Olive growers, too, have suffered: at a grove in Kibbutz Afek near Shefa-Amr, mother and son Mina and Karmi Hassan were killed. Just five days ago, teenager Sivan Sadeh lost his life while working in the broccoli fields near Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk, miles from the Lebanese border. “When they report ‘strikes in open fields,’ they’re talking about our workplaces,” said Yossi Barash, owner of Barash Farm in Yesud Hama’ala.

He acknowledges that, ideally, the Iron Dome air defense system would protect the entire country, even areas with minimal risk of casualties, though he understands this isn’t feasible.

“It feels like history is repeating itself,” he said—not nostalgically. “Before the Six-Day War, farmers in Yesud HaMa’ala struggled to tend their fields due to Syrian shelling, and now we’re dealing with Hezbollah’s fire. Harvesting olives this year has been even harder than last year. When the war began, volunteers from pre-military programs and various organizations came to help, but now they aren’t allowed to come under Home Front Command orders.”

Despite the challenges, Barash is determined to hand-pick every last olive himself, with a few foreign workers by his side. “My ancestors dried out swamps here and fought malaria. Farmers are stubborn and resilient. We won’t be the ones to abandon our land or forsake agriculture.”

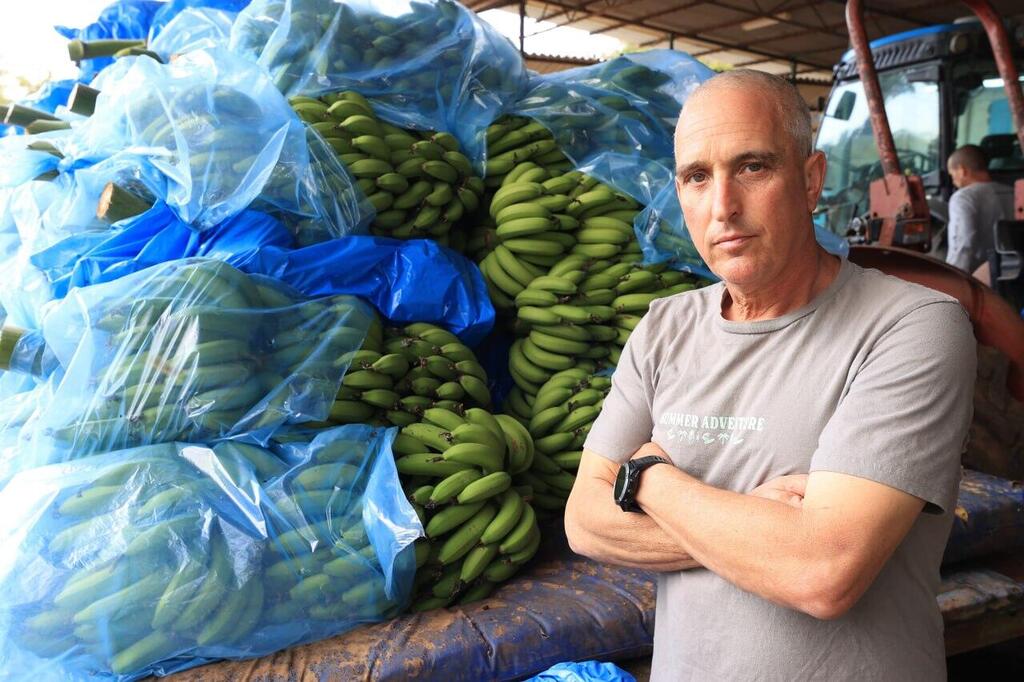

Their dedication to the land may be hard for outsiders to understand, but farmers explain that it’s driven by Zionism—and, of course, the need to make a living. Eyal Ovadia, chair of the Banana Growers Council and CEO of Western Galilee Banana Growers, noted that “since October 7, Israeli farmers have been forced to work under rocket threats, with only limited access to their crops, some of them evacuated and often without any shelter at all.”

He sees farmers as “the first line of defense in the battle for food security, paying with their lives so that Israeli citizens can continue to have a steady supply of fresh food.”

Ovadia added that the eight farmers killed across the Galilee in one week “were following the guidelines—when the sirens go off, they lie on the ground, hands on their heads and pray. I send my deepest condolences to all the families, and I hope that Sivan Sadeh will be the last victim.”

Despite the sacrifices and constant danger, Ovadia hopes the public will show their appreciation, “We’re coping with an almost impossible reality, and the fire only intensifies. The public needs to support us by buying more locally grown produce.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: