Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"Siret did not meet the expectations. A remote village on the border of the Soviet-era Iron Curtain, where time seemed to have stopped. So primitive, I remember telling myself, as I saw the women drawing water from a well in the central square," wrote Nava Semel after her visit to Siret in Romania, near the border with Ukraine, the birthplace of her father, Itzhak-Izhu Artzi.

More stories:

The visit to Siret by Itzhak and Mimi Artzi, their children Shlomo and Nava, their son-in-law Noam and daughter-in-law Milka, raised a question in Nava's mind that she says has continued to "haunt me ever since, and I still have no answer – how did Zionism reach this remote place? How could it snatch an eleven-year-old boy from an ultra-Orthodox family, enchant him until he abandons everything he was raised upon, and dedicate his life to some intangible Palestine on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea?"

When we arrived in Siret, the entrance to the town was almost completely blocked. Now the town is bustling with activity and holds great strategic significance for Western countries in general and Romania in particular.

If Itzhak Artzi were to visit his birthplace today, he would be astonished by the recent developments. In his autobiographical book, "Just Zionism," he wrote about Siret, which is located "in the region of verdant hills, one of the ancient cities in northern Romania."

Surely, he would be surprised by the sight of the entrance to the town, where a three-kilometer-long procession of more than 250 gigantic trucks, each carrying at least 40 tons of goods (from fuel to food, toiletries and household items) from the European Union to Ukraine. Siret, with its narrow roads and impoverished population, is the sole and only point for all the goods passing from Romania to Ukraine, embroiled in conflict with Russia. Approximately 750, and sometimes even 1,000, trucks pass through Siret daily over the past year. “On our roads,” says Mayor Adrian Popoi, “at least a million tons of goods pass each month.”

True Jewish life thrives in Bucharest

The trip came as part of a program that focuses on aiding small Jewish communities to establish daily Jewish schools and organized Jewish education.

Genuine Jewish life, in its fullest sense, thrives in Bucharest. Synagogues, schools, mikvehs, the Jewish Museum and even a Jewish theater are all flourishing these days in Romania, presenting Nava Semel’s play "Speak of Their Whereabouts." The play was written following a popular radio show on searching for relatives that aired for many years on Israeli radio. The play, which has achieved and continues to achieve tremendous success in Israel, receives exceptionally positive reviews in Romania as well.

Testimonies of Jewish life before the Holocaust

One of the focal points of the trip is the subject of the Holocaust in Romania, which is presented by Yad Vashem guide Naama Egozi. The second topic is the Jewish life that thrived in hundreds of villages and towns across the country before the Holocaust. The existence of these rich and flourishing Jewish lives is documented by hundreds of physical testimonies. Throughout Romania, in villages, towns and cities, one can see synagogues still standing intact. They stand as monuments, and in many places, one can witness stunning structures in their grandeur and beauty.

Only a few of these synagogues remain open, and only in very few of them, prayers are still held. Out of the 800,000 Jews who lived in Romania before the Holocaust, over half perished between 1940-1944. Each town has its own tragic story and the term "Transnistria" echoes, where 250,000 Romanian Jews were murdered.

Yitzhak Artzi, born Izhu Herzig, is the unsung hero of rescuing Jewish children from Transnistria. He saved over 2,000 Jewish children from the inferno beyond the Dniester River.

Today, everyone talks about "Jews saving Jews." The greatest Jewish rescuer was Yitzhak Artzi, and I often wonder why, to this day, no academic researcher has examined his unique activities.

He recounted in his book, "In January 1944, we set out on our journey. The ride from Bucharest to the Transnistria border took hours. We passed through the entrance gate of Mogilev Ghetto. Elderly, disheveled people wrapped in rags of sacks and blankets stood there. They stared at us and whispered. No one dared to approach us. Within minutes, the rumor of our arrival spread."

In his book, Artzi extensively describes the great rescue operation, which, unfortunately, didn't receive the recognition it deserved.

However, our objective is to uncover the roots of Nava Semel, especially the town of Siret and the larger town of Suceava, where her mother, Mimi-Margalit Artzi.

During our long journey, we stop in Piatra Neamț, the city where the synagogue bears the name of the Baal Shem Tov. Legend has it that the founder of Hasidic Judaism made a stop there during his journey to the Land of Israel, a journey he never completed. The synagogue has undergone significant renovations, but no prayers are held there.

On our way, we pass cities and towns whose names I knew, but time constraints didn’t allow us to stop in Focșani, where the First Zionist Congress was held in January 1882. Fifty-one delegates from 32 settlement societies in the Land of Israel convened before the First Aliyah began and more than 15 years before the World Zionist Congress in Basel, discussing practical aspects of Jewish settlement in Palestine.

Siret 2023: Not a single Jew left

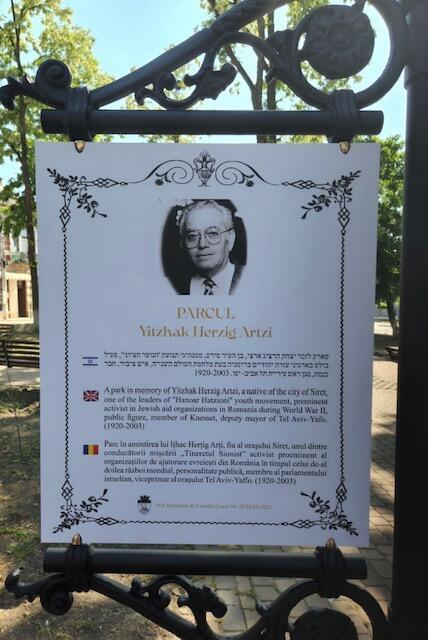

About a year ago, a public park was dedicated in Siret in honor of Yitzhak Artzi, right in front of the house where he was born and raised. However, at that time, the work was not completed, and during our visit, the park was fully opened. We asked the local mayor to help us visit the Herzig family's apartment in the beautiful house opposite the park.

With the help of the local "sheriff," who has been serving for 16 years, we were able to visit the Herzigs’ apartment. During our city tour, we carry with us Artzi’s biography and read from it as we walk. We begin at the inauguration ceremony of the park, and from there, just as Yitzhak wrote: "Our house was situated on the street leading to the ancient cemetery."

The mayor leads the way, followed by a relatively large group of Israelis. There are no tourists in the town today, which has a population of about ten thousand residents, just like in 1940, but there were also 3,500 Jews living in the town, the largest group at the time. Today, it seems there isn't even a single Jewish resident.

The mayor passes by the ancient cemetery, dating back to the 14th century, and takes us to the new cemetery. The tombstones are in good condition, and it's easy to identify the Jewish symbols and read the mournful words engraved or written on them. The graves are covered with lush green grass, making it easy to stroll around and identify the names of the deceased.

Suddenly, Benjamin Ross - the youngest member of the group, a lone soldier from the United States and a relative of Artzi’s - suddenly announces that he has found the tombstone of his great-grandfather, Abraham Katz. Standing beside the tombstone, he recites Kaddish.

The special leave he received from the IDF to explore his roots in Romania takes on a profound significance, and he quickly sends photos of the touching moment to his excited family back in the United States. Finding the grave of a relative is often the pinnacle of such trips, and here in the town of Siret, the "miracle" unfolds before us.

With the inauguration of Yitzhak Artzi Park, the Herzig family returned to the town. Noam Semel eagerly shared stories about his father-in-law, whose picture appears on a beautiful plaque placed in the park. The Herzig family home still stands, the synagogue building remains intact, and the tombstone bearing witness to the family's history was found. Siret, about which Nava wrote, "In the early '80s, dad wanted me to accompany him to Siret - the place of his birth in Romania. Until then, I had little interest in the past," became a central theme extensively covered in her best-selling book Fanny and Gabriel, a wonderful novel filled with tales about her paternal grandparents.

Dorohoi Pogrom

"On July 1, 1940, the funeral of the Jewish soldier Iancu Solomon took place in Dorohoi. A guard of honor of Jewish soldiers was sent to the cemetery... As the coffin was lowered into the grave, rifle shots were heard. The Romanians supervisors ordered the Jewish soldiers to leave the cemetery... At the entrance to the cemetery, another unit separated the Jewish soldiers from their weapons and opened fire on them... Not much later, and the assailants slaughtered another forty Jews." This is how historian and Holocaust researcher Prof. Radu Ioanid, currently the Romanian ambassador to Israel, describes the beginning of the Dorohoi Pogrom, which occurred 83 years ago, just before Romania entered World War II.

We arrive in Dorohoi with Eran Berkovic of the Jewish Agency delegation. His parents were originally from Dorohoi, and he was visibly excited although it wasn’t his first time visiting the city.

In 1940, the community in the area amounted to over 5,000 Jews, about a third of all residents at the time. Today, only a few Jews live in the city and the only synagogue is locked and closed, although it is possible (without confirmation) that it opens for the High Holy Days.

Near the synagogue, Eran recounts what his parents told him about the horrors of those days, when innocent Jews were killed. According to official Romanian records, 53 Jews were killed in the pogrom; members of the community and survivors speak of a much higher number, between 165 and 200.

A colleague, whose family also originally hails from Dorohoi, sent me updates from Israel on other Jewish sites in the city that survived, but we turn to the Jewish cemetery outside the city.

We met Ilya and his wife Burdetska who take good care of the place. Ilya, a Christian local who loves Jews and has children who immigrated to Israel and became citizens, leads us to the mass grave of the Jewish who were killed in the pogrom 83 years ago. The group, especially those who had never heard of the city or the pogrom, were moved by Eran's retelling of the story at the cemetery.

Suceava

The geographical distance between Dorohoi and Suceava, where Nava Semel’s mother was born, is not great. The first meeting between Yitzhak-Izhu and Mimi was in 1938 when they both studied in Chernivtsi, a beautiful city that is now located in Ukraine and is not recommended for travel today. They were just friends at that time, nothing more.

The post-Holocaust meeting, eight years later in 1946, occurred when Yitzhak and his mother, came to bid farewell to their home in Siret. While in Suceava, Yitzhak and his mother attended a Jewish party where Mimi-Margalit was the star. The love between them quickly blossomed, and within a short time, this Jewish survivor couple established a new family.

Her mother’s birthplace was no less important to Nava Semel than her father’s. I have been to the provincial town of 90,000 residents where Mimi was born before, but this time, spending the Sabbath here gives me an opportunity to ponder the Jewish world in which her mother was raised.

Even today, there is a small Jewish community in the city; prayers are held only in one of the eleven synagogues that existed in the city before the Holocaust. Memories shared by her grandmother and mother offer glimpses into the past.

Noa took pride in her mother's family, a family with a rich Jewish heritage. Her grandmother was the sister of Rabbi Meir Shapiro, the founder of Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva and the initiator of the "Daf Yomi" study cycle in the Talmud. For years, Nava shared a room with her grandmother. When she woke up in the morning, she would see before her the picture of Rabbi Meir Shapiro with his radiant eyes.

The Shapiro family had an illustrious lineage, and Mimi's cousins included the late Naphtali Lau-Lavie and his brother, the former chief rabbi of Israel, Yisrael Meir Lau. Other cousins were the late Prof. Pinchas Peli, the late Rabbi Shmuel Avidor Hacohen and Rabbi Menachem Hacohen. With such roots, it's no wonder that Nava pursued a bit of Yiddishkeit, as depicted in her books.

At Shabbat dinner in the city of Suceava, around the tables where candles were lit every week until 1941, Noam Semel recounts in his unique way the story of the family connection between Mimi Artzi and the city we are staying in. These candles, which his daughter Ilil Semel, lights every week, are a memory torch, entrusted to our hands during Shabbat, through which we remember Nava’s legacy and that of her family. It has been passed down from generation to generation, without forgetting the past or disregarding the future.

As the candle lighting concludes, we sit around the tables in Suceava, after visiting Siret and Dorohoi, and we gain a better understanding of Nava Semel who began writing about the Holocaust, becoming one of the "second-generation" writers, only after his mother opened her heart and shared her account with her.