I catch up with Nissim Saal, the new star of the cantorial world, at his home in Staten Island, New York, just a few hours before he boards a flight to Israel with his family. He is going to assume a new and challenging role for the New Year: the hazan, or cantor, of the Yeshurun Synagogue in Jerusalem.

More stories:

The Yeshurun Synagogue, which has already celebrated its 100th birthday, is considered one of the prestigious synagogues for cantors. It is also one of fewer than half a dozen synagogues in Israel that have a resident cantor.

Some argue that Saal even threatens the number one star of the cantorial world today — Yitzchak Meir Helfgot, 54, from the U.S., who is the most sought-after and highest-paid cantor in the world, serving as the house cantor of the Great Park East Synagogue in Manhattan, New York.

Saal's entry into the role symbolizes the changes occurring in one of the most conservative professions in the Jewish world: the cantor. While the cantor's main job is to serve as a prayer leader in synagogues, the role also includes public performances—sometimes for secular audiences—in halls and events.

The shifts in the contemporary public's mood, in a world of fast-paced living, include among other things a search for new thrills and stars, a decline in the older audience who appreciate cantorial music, and a need both for synagogues and for concert organizers and "cantorial Shabbats" (a weekend of leisure accompanied by cantors who lead the prayers, sing at meals, and also give performances) to increasingly attract young people to love the field.

Saal is aware of the changes. "I see today many more yeshiva students, both young and old, coming to prayers with professional cantors in synagogues and also to performances in concert halls. Cantorial music is a beautiful art form. But I believe it has not been presented correctly in recent years. If I and others present it correctly, we will see results."

The story of Saal (39, married with 3 children) is not typical in the cantorial landscape. He is of Syrian-Argentinian descent, sings, and is proficient in the Ashkenazi liturgical tradition. He grew up in the Satmar-Kiryas Joel community in Monroe, near New York, to parents who were returnees to religious observance and came from Argentina.

Unlike established stars in the cantorial world, he did not participate in children's choirs in synagogues during his youth and was never labeled a "child prodigy." "As a child, I obsessively listened to the cantorial pieces of Yossele Rosenblatt (one of the greats in the Ashkenazi cantorial world, composer and performer, who lived between 1882–1933). I would also sing them endlessly, locking myself in a room and listening to my small tape so as not to disturb the family."

There, and also at family events, the seeds were sown, but for the past 18 years, Saal has primarily worked in planning and building real estate projects, a job he is still trying to maintain. "I left cantorial music, perhaps also because I did not think it had a future."

Then, two years ago, his two eldest children, aged 17 and 19, decided to bring him back to the profession. "They didn't let go of me, they said: 'Maybe you should do something.' I laughed, at my age?"

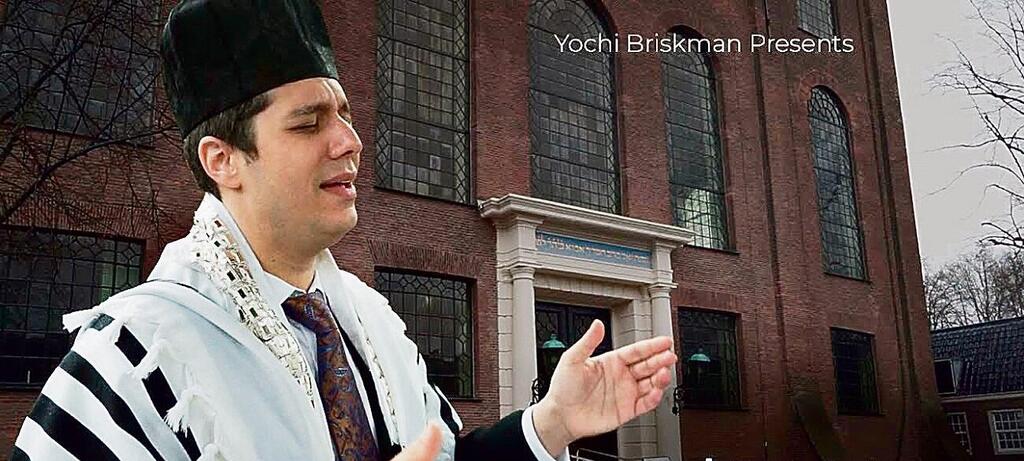

Cantors usually start their journey into cantorial music between the ages of 10 to 20 at the latest. Despite this, Saal was convinced and began to release videos, and one of them caught the ear of Yochi Briskman, a leading American-Jewish conductor, organizer and producer in Jewish music. Briskman told him, "You will be a great cantor," and decided to turn him into a star.

Most struggle to make a living

The cantor of a synagogue leads the prayers for the High Holy Days—Selichot, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur—in the synagogue, as well as the prayers for the Three Pilgrimage Festivals—Sukkot, Passover and Shavuot—and additional prayers for 12-20 Sabbaths a year. On other Sabbaths, and of course on weekdays, he is free to perform at events. How much do professional cantors earn?

"The traditional peak season for the world of cantors is the High Holy Days, from Rosh Hashanah to Sukkot. The good cantors, who go to synagogues abroad (which pay much more than in Israel), will receive between 10,000-15,000 dollars, including expenses. A few will even reach 20,000-40,000 dollars gross"

The traditional peak season for the world of cantors is the High Holy Days, from Rosh Hashanah to Sukkot. The good cantors, who go to synagogues abroad (which pay much more than in Israel), will receive between 10,000-15,000 dollars, including expenses. A few will even reach 20,000-40,000 dollars gross. This is for the period from the evening of Rosh Hashanah until the day after the end of Sukkot, which is Simchat Torah abroad.

"There are those who travel abroad just for the cost of the plane ticket, and many will receive only 3,000-5,000 dollars in addition to the ticket," says veteran cantor Israel Rand, 60, who is today the resident cantor of the main synagogue in Ramat Gan, considered one of the mentors and nurturers of cantorial art in Israel.

Here in Israel, very few cantors will receive more than NIS 20,000 for the High Holy Days. And how much do they earn for concerts and events? The few in-demand ones will receive 15,000-20,000 dollars per concert, both in Israel and abroad. For them, joining a weekend with vacationers (see below) will also yield a salary of 20,000-30,000 dollars.

Second and third-tier cantors will receive 7,000-13,000 dollars for a concert and NIS 6,000-10,000 for a weekend. Still, these are limited numbers. Many cantors find themselves earning a living through music lessons, conducting, arranging and work outside the world of music, such as a well-known cantor who is also a high-tech worker.

The reason is that the synagogues interested in cantors are becoming fewer, and only a few of them have the ability and interest to fund leading cantors. There are many people with good and even excellent voices who are happy simply for the fact that they are invited to stand before the ark (in a synagogue).

"The biggest problem in the field of cantorial music today is making a living. Few cantors make a living solely from cantorial work, and most are not in the profession for the sake of income. Despite this, it doesn't prevent the influx of new voices into the field," explains one of the veteran fans and patrons of the world of cantorial music.

"At the beginning of each school year, I tell my students: if you thought you came here to find a livelihood, to stand in a concert hall tomorrow—forget about it, it's a waste that you came. At most, you will get a job that pays a few thousand shekels a month," admits Rand.

The amount of people making a respectable living from cantorial music is very thin worldwide. Yitzchak Meir Helfgot is the only one who, according to estimates, breaks the million-dollar-a-year mark—from cantorial music alone. In addition to his salary from the synagogue where he serves as the resident cantor, he earns, according to estimates, about $250,000 a year (before the expenses of living with his family in Manhattan during the holidays and weekends, as he resides in Brooklyn). This is in addition to performances at private events and concerts.

"To book Helfgot, you need to do it a year in advance. When we finish our annual 'Shabbat of Cantors' in January, we are already scheduling the next one," says Dafna Cohen, owner and tourism entrepreneur of the company Tour Plus.

Cohen, along with her husband Yaakov, who is the CEO of the company, initiated the first 'Shabbat of Cantors' 25 years ago, which has since become a tradition. "In such a Shabbat in Jerusalem, [Helfgot] also had one of his first major breakouts. He came as a guest, was asked to sing something, and the audience was left breathless."

The Cohens also initiated the inclusion of cantors in vacation events organized by the company both in Israel and abroad during summer vacations, Sukkot, and Passover.

This coming winter, they will bring to the Dead Sea David Hotel both Helfgot and the star cantor Shalom Lemmer, the first ultra-Orthodox Jew to sign a contract with Universal Music Group.

Lemmer is the resident cantor of the Ahavat Torah community in Englewood, New Jersey, and some argue that he is more of a singer than a cantor. Cohen hopes that more than 1,000 people will come to the hotel vacation to hear the two stars.

Helfgot, a Ger Hasid who performs in concerts with a mixed religious and secular audience, was born in Israel. His legendary voice was discovered in his childhood. He began as a member of the large children's choir of the Ger Hasidic community.

When he matured, he became a cantor at a synagogue in Frankfurt, entered the concert scene, and the rest is history. Since then, he has lived in the United States.

"He is blessed with an extraordinary musical memory and easily tackles the most complex compositions. He performs in a shtreimel (Hasidic fur hat) on Shabbat in Manhattan, but is sought after around the world, having also performed in China, Japan and Turkey. Non-Jews have come to hear him too, and he even released a joint album with violinist Itzhak Perlman," says one of the longtime cantorial enthusiasts with whom I spoke. We were unable to obtain Helfgot's response despite our best attempts.

Another star is Joseph Malovany, the veteran cantor of the synagogue on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. There are also cantors who are seen more as stars of the past but are still esteemed, such as Naftali Hershtik, the former cantor of the Great Synagogue in Jerusalem, and Yaakov Motzen, 74, who resides in the United States.

Motzen previously served as the chief cantor in a series of synagogues in Canada and the United States. Today, he is not affiliated with any particular synagogue but is considered a teacher and a guide to the new generation of cantors.

"If it's so hard to make a living from it, why are you investing in cantorial studies?" I ask M, an architect and father of five, who decided in his 40s to spend two days a week on a two-year course for cantorial studies at one of the three schools for cantorial training operating in Israel (in Tel Aviv, Petah Tikva and Jerusalem), which prepare dozens of students each year.

"The love for it comes from my father, who has been a cantor, albeit not a famous one, for decades. I've always wanted to study. A voice is a gift from heaven. But in cantorial singing, just like in opera, you need to reach unprecedented heights, to carry out trills in length and octaves that an average person can't perform. You have to learn the techniques. It was important for me to learn. That includes reading sheet music, choir lessons, and also understanding the liturgical text in depth," says M, who is committed to realizing his dream despite being uncertain about its future.

Architect and cantorial student

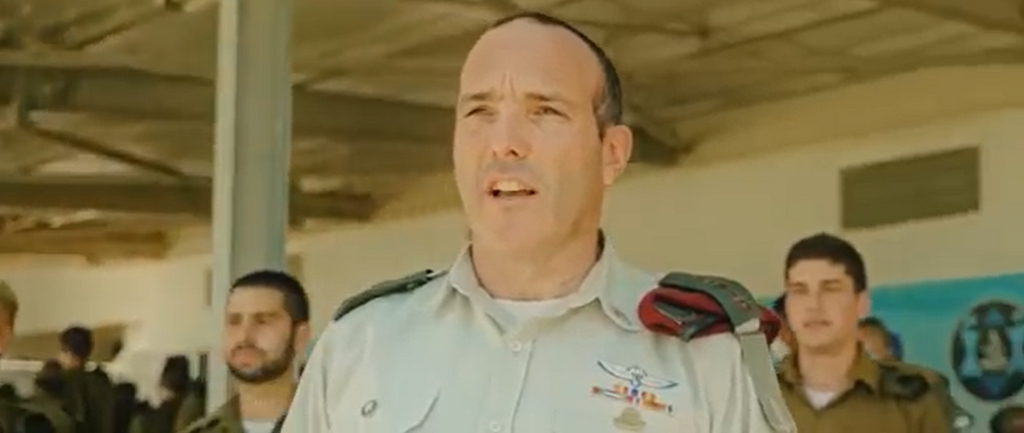

Shai Abramson has been the chief cantor of the IDF for the last 16 years. According to him, he owes his entry into this world to Gabi Ashkenazi, the then-chief of staff, who was impressed when he heard his cantorial performance at a festive event honoring Benny Gantz — himself a cantorial enthusiast, whose grandfather was a cantor.

Abramson comes from a musical family and sang as a child in the prestigious choir of the Great Synagogue in Jerusalem. However, in the IDF, he was involved in technology and logistics, reaching the rank of major. He then made a shift to cantorial singing.

“When I started doing what I love and received feedback from both Israel and abroad, including from bereaved families but not only, I felt divine guidance,” he says. “I've been in the role for 16 years, and every day has its own excitement. This year, I'll celebrate my 50th birthday. Sadly, I already have friends who have passed away, and friends who are sick. I get deeply moved at the end of the prayer U'Netanneh Tokef, especially with the words, ‘Man's origin is from dust and his destiny is back to dust, at risk of his life he earns his bread; he is likened to a broken shard, withering grass, a fading flower, a passing shade, a dissipating cloud, a blowing wind, flying dust and a fleeting dream.’

“I think about my loved ones going through hard times, and I can't finish without starting to cry and choking up. And the congregation responds. When the cantor chokes up, it touches the heart.”

Abramson will spend Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in Toronto, flying there with a five-member choir, and will sing at the Shaarei Shamayim Synagogue. Because there are not many synagogues that employ cantors on a regular basis.

The cantor is the representative of the community according to halakhic (Jewish legal) literature, and his role is to fulfill the prayer obligation on behalf of the entire congregation, in other words, to elevate their emotional and spiritual involvement in prayer.

However, there is a whole Jewish world where synagogues do not employ cantors but rather what is called ba'alei tefillah (prayer leaders), whose singing is less complex and concert-like and more straightforward. Their work is considered a merit and an honor, and they do not receive payment for it. This is true in all Hasidic worlds, including the largest synagogues in the world, which belong to Hasidic rebbes, as well as in the synagogues of the yeshiva world and its graduates.

In the 1920s and 1930s, cantorial music moved beyond synagogues to concert halls and recording studios. In the past, you could see a significant number of secular people in the audience at every cantorial concert. For example, former Tel Aviv Mayor Shlomo (Cheech) Lahat and Supreme Court Judge Dov Levin were avid fans of cantorial music.

“Today, you still see secular participants in the audience,” says Ofir Sobol, a conductor, arranger and musical producer, who continues the work of his late father, Mordechai Sobol, as the director and conductor of The Israeli Ensemble for Yuval Cantorial Music, which has contributed greatly to cantorial music in Israel.

Each concert of the ensemble attracts over 2,000 people. The majority are men, although more and more women have been joining in recent years.

Sobol: “Lately, we've noticed former IDF generals, such as Yoram Yair (Ya Ya) and others. Some come with their families. At concerts, I also saw Frank Lowy, the famous Jewish-Australian mall owner; businessman Rami Unger; even Ehud Olmert and Shlomo Baraba; not to mention Supreme Court Judge Elyakim Rubinstein and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich — a clear cantorial enthusiast."

However, the number of secular fans of cantorial music is dwindling. The younger generation is less connected to the heavy, ornate musical compositions that last 15-20 minutes. The connection to the texts is also weakening in the secular world.

The late Shimon Peres wanted to include the prayer Avinu Malkeinu, recited on Yom Kippur, in his 90th birthday celebration and his funeral, a prayer that had resonated with him since he heard it as a child under his grandfather's tallit.

But to the younger secular generation, the cantorial texts from holiday prayers sound like Sanskrit. The challenge is to attract young people to ensure the future of the profession—agree the cantors and organizers with whom I spoke.

“We don't give up on classical cantorial music, but for example, we present it in lighter arrangements, like singing the Prayer for the State [of Israel] to the tune of the well-known song Eretz Hatzvi from the film about Entebbe, composed by Dubi Zeltzer,” reveals Cohen.

“Today's audience wants excitement,” says Motzen in a conversation from the U.S. “They are interested in the highest note that the cantor can reach, and they don’t understand that the emotional experience can only be achieved when the cantor, and preferably also the congregation, understands the prayer.

“Many in the religious community, including cantors, lack understanding of the text. Many in Israel and abroad come to synagogues because of friends; they are looking for the social experience, and fewer and fewer synagogues abroad can afford to maintain a full-time cantor with a salary of $150,000 a year."

Ani Ma'amin - Yitzchak Meir Helfgot, Shlomo Glick, Nissim Saal and Zvi Weiss, accompanied by the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra

(Photography and editing: Grovais Productions; Initiative and production: Benevel Assor)

Nevertheless, Saal believes that there is a future for the world of cantorial music. “People have told me that some will say it's a dying or waning profession, but I see the feedback from the public. The profession is alive, and it definitely has a future,” he says.

Many believe that Saal will indeed manage to make a change in this world. “He is blessed with a rare vocal range,” says Sobol, and Motzen adds, “He will succeed because, in addition to the gift of voice, he is willing to learn and takes any criticism in the right way.”

Private house cantor for the wealthy

Few synagogues today maintain a house cantor. Aside from the main synagogue in Ramat Gan, with Cantor Israel Rand, among the few who still do this is, for example, the Great Synagogue in Jerusalem, with two rotating cantors and a large choir. But as in every field, cantorial music also has its own narrow elite layer. This refers to about a dozen private synagogues of wealthy Jews who employ their own house cantor—in Israel, Canada, South America and the U.S.

One of the most famous is the Baal Shem Tov synagogue in Wesley Hills, an upscale Jewish neighborhood north of New York. The synagogue was built according to the original design of Baal Shem Tov's synagogue in Mezhibuzh in Poland, including original bricks from that synagogue, as well as fragments of stones from the foundations of the bunker of the ghetto fighters on 18 Mila Street in Warsaw. The wealthy founder, David Lichtenstein, often hosts top cantors like Yitzchak Meir Helfgot or Shalom Lemmer, complete with a choir.

“In recent years, we are also seeing a phenomenon where wealthy people will invite, for Sabbaths, housewarming ceremonies or bar mitzvahs, a well-known cantor, and even a choir of up to 40 children, adults or both. Particularly popular and a rising star as an event conductor is Rafi Biton,” says Cohen.

There are even wealthy families who, during the holidays, travel with the entire extended family to vacation on one of the resort islands—and take a cantor along with them.