Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

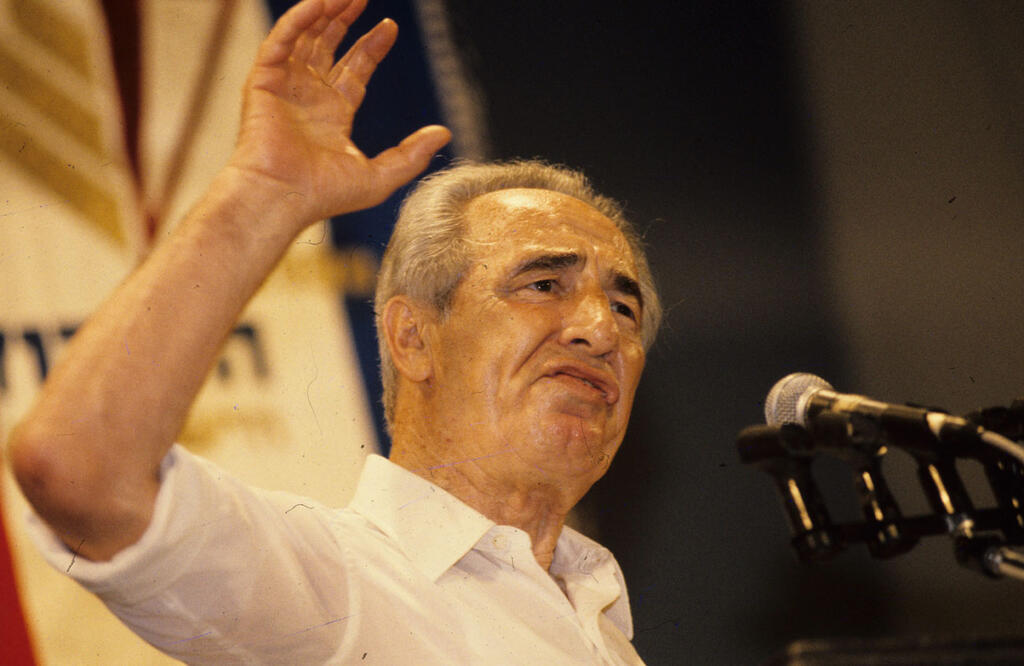

Exactly 30 years ago today, on August 20, 1993, Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and Foreign Minister Israeli Shimon Peres signed a document known as the Oslo Accords. These accords were the result of secret talks held in the Norwegian capital and aimed to establish a five-year transition period for managing relations between Israel and the Palestinian population in the "occupied territories."

Read more:

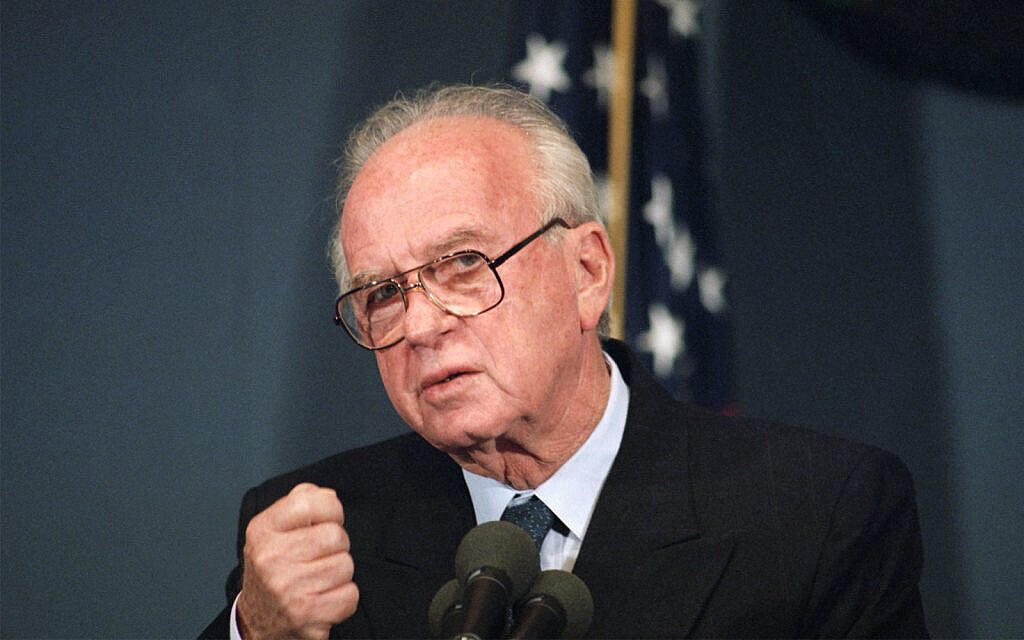

Israel officially recognized the PLO as the legitimate and exclusive representative of the Palestinian people, while the PLO, in turn, acknowledged Israel's right to exist in peace and security. A short while later, the initial document developed into a set of core principles that won approval in the Knesset by a narrow margin of 61 votes and was subsequently signed on the White House lawn. The event also featured a historic handshake between Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat.

9 View gallery

Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat shake hands at the signing ceremony of the Oslo Accords at the White House; in the middle: US President Bill Clinton

(Photo: AP)

The addendums to the interim agreement outlined numerous fields for economic collaboration in developing the "customs union." After a year of negotiations, challenges and innovative problem-solving, the Paris Protocol was finalized in April 1994. This document not only established economic ties between Israel and the newly formed Palestinian Authority (PA) but also set out guidelines for their future relations.

This protocol established a customs and taxation framework that spanned all of Greater Israel, facilitating the free movement of goods, individuals, ideas and financial assets between Israel and the territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip under Palestinian governance.

The agreement stipulated that Israel would continue to administer taxes and customs at the outer borders of this framework while retaining the exclusive right to issue its currency, the shekel, which would be considered legal tender across these territories. In addition, the management of the Palestinian internal economy was handed over to Palestinian authorities. All of this, theoretically speaking.

The Paris Protocol stood as a significant achievement upon its signing and has remained unshaken, despite its revealed gaps and subsequent alterations, to this very day. Is this advantageous or detrimental? When reviewing reports published by international bodies, designed to secure resources and support for the PA, the economic outlook consistently appears grim. Whether you read one report or several, the economic situation is persistently dim.

"The envisaged close trade and financial integration between Israel and the Palestinian territories should have led to gradual income convergence, implying higher per-capita growth of Palestinian incomes than has been seen. But the conditions for such growth were not realized and income convergence has not happened," the International Monetary Fund said in a report this April.

This largely can be attributed to Israel's stringent and constrictive policies. An economist for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) projected an economic loss of $50 billion for the PA due to the restrictions Israel has imposed over the last two decades. Conversely, the profits reaped by the Israeli economy from settlements in the West Bank, as outlined in the same report, stood at a staggering $630 billion, more than double Israel's annual domestic output.

Old Middle East

However, even before delving into the numerical aspects, which undoubtedly hold substantial significance, it's genuinely fascinating to delve into the trajectory that the ambitious concept of the Oslo Accords and Paris Protocol, often referred to as the "New Middle East," took. The inception of this term owes much to late Israeli president Shimon Peres who first coined it during the October 1994 economic summit in Casablanca, Morocco focusing on the Middle East and North Africa.

This particular event left an indelible mark in the memory of all attendees, characterized by the lofty promises and aspirations that animated its discussions and interactions. A massive assembly of over 1,500 eminent politicians, heads of state, representatives of organizations, corporations and media outlets gathered in the picturesque coastal town which primarily owes its fame to the iconic 1942 movie Casablanca, starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.

Four full passenger planes left for the conference from Israel. The official delegation brought with it a hefty, 400-odd-page book replete with meticulously crafted maps, diagrams, evocative photographs and informative charts. The book's title, Regional Options for Development and Cooperation, was a fitting reflection of its contents. This comprehensive document detailed Shimon Peres's ambitious vision for building a reinvigorated Middle East.

It mapped out pragmatic initiatives spanning various sectors: agriculture, energy, transportation, water management and tourism. Notably, these initiatives were intended to foster collaboration between Israel, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and North African states. Interestingly, the roster of projects (and Peres's statements at the time) conspicuously omitted any mention of Palestinians as a governing body with a stake in shaping their destiny. In essence, they were conspicuously absent from the narrative of the summit's discussions and aspirations.

The Casablanca Summit was characterized by warm embraces between U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian counterpart Boris Yeltsin at dinner, lengthy speeches that painted vivid visions of a promising future for all participants, and yet, astonishingly, resulted in zero – yes, you read that right, zero! – concrete agreements. As the delegations departed, their hands remained conspicuously empty.

The document the Israeli delegation carried has had as many versions as the number of Middle East economic summits that followed. These gatherings included Rabat (taking place just days before Rabin's tragic assassination), Cairo (following Netanyahu's first electoral triumph) and one held on the Jordanian side of the Dead Sea.

Remarkably, these gatherings yielded nothing substantial in terms of concrete outcomes. The grand vision of establishing cross-border power grids remained unrealized, the joint endeavors to develop shared tourist sites remained elusive, the ambitious plans for trans-border roads and railways continued to linger as unfulfilled aspirations and even the collaborative efforts to tackle the burgeoning water crisis met an untimely demise.

The notion of an interlinking water canal connecting the Red Sea and the Dead Sea, once touted as a game-changer, now languished in obscurity. Israel's integration into the broader Middle Eastern economic framework remained a deferred dream – an aspiration that only gained a foothold in recent times, chiefly within the specific domain of natural gas exploration and use.

Among the limited success stories stood textile manufacturer Delta, masterminded by the late peace advocate Dov Lautman, which established sewing factories in both Jordan and Egypt, using U.S. customs benefits. It's pertinent to highlight that the budgets allocated for defense in the region remained largely untouched, defying the proposed reductions tabled by Rabin and Peres during the Casablanca Summit.

The Palestinian economy's data is compiled and analyzed by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Three decades ago, following the Oslo Accords, this responsibility transitioned from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics. While I certainly do not intend to undermine the expertise of Palestinian statisticians, I feel it's essential to exercise caution in placing undue significance on the numbers they present.

Over time, the key Palestinian economic indicators are periodically revised, leading to a complete transformation of the overall outlook, often in a considerably more favorable light. Furthermore, significant portions of economic transactions in the territories are conducted unofficially and remain unreported. There's a notable lack of available information regarding the economic dynamics of Hamas-controlled Gaza and the scope of its financial inflow.

Additionally, the Palestinian bureau, driven by explicit political motivations, is currently releasing economic activity data for the territories in U.S. dollars, a choice that significantly distorts the real situation. The U.S. dollar is not legal tender in these areas and doesn't play a role in commercial transactions.

It's important to make a clear distinction between the gross domestic product (GDP) within the territories under PA rule, which measures all the final goods and services produced there annually, and the gross national income (GNI) of the Palestinian people.

GNI includes various sources, such as earnings from work in Israel and Israeli West Bank settlements (amounting to around $3 billion last year), remittances from Palestinian workers employed in Gulf countries, aid provided by supportive nations (ranging from $800 million to a billion dollars annually), as well as aid from various UN agencies. As a result, the PA's GDP accounts for roughly 22% to 25% of the local GNI.

Lastly, the issue of prices: The cost of living in the Palestinian territories is very low across the board. Therefore, in terms of real purchasing power, the per capita income for a Palestinian is higher than the basic dollar calculation might suggest. The World Bank database provides estimates of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) adjusted per capita income in Palestine (as per the global lender): $8,200 last year.

For comparison, the GDP per capita was only $3,700 last year. The PPP adjusted per capita income in the West Bank alone was estimated at $12,300. In contrast, the GDP per capita stood at just $5,500. This figure doesn't accurately reflect the standard of living in the PA-ruled territories in the West Bank.

Nevertheless, international economic institutions rely on the local GDP to describe the Palestinian economic crisis. This approach is problematic and demoralizing, and it doesn't even serve their own objectives.

Between the West Bank and Gaza

When the Oslo Accords were inked, there wasn't a significant economic gap between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Back in 1994, the average national income per person in the West Bank (excluding Israeli settlements and East Jerusalem) stood at $1,370, while in the Gaza Strip, it was $1,260. The gap was just 9%.

At the height of the Second Intifada in 2002, the income per capita for a Palestinian resident in the West Bank was already 30% higher than their Gaza counterparts. Since then, the income per capita in Gaza has grown by 45%, while in the West Bank, it has ballooned by 380%. In reality, these are now two distinct economies with very little connection between them, except for the salaries of the public-civil sector workers in the Strip, which are still paid from PA coffers in Ramallah.

The economic situation in Gaza is dire. Nearly 40% of the labor force is without work and the average local wage is NIS 1,200 per month ($312). The aid from donor countries is swallowed up in the financial labyrinth of Hamas bureaucracy. Exports through Israeli ports face security and bureaucratic obstacles. Investment in crucial infrastructure falls well short of what's necessary.

Energy supply is intermittent, water is polluted, housing density in refugee camps increases year by year and access to fundamental healthcare and education services is far from adequate. The grip of poverty refuses to loosen.

A silver lining: Since the leadership of Hamas in Gaza was replaced, socio-economic issues have been placed at the top of Yahya Sinwar's priorities. There has been a notable uptick in business activity, certain projects in the energy and water sectors are finally nearing completion and Israel is granting entry permits to thousands of workers.

Compared to Gaza, the PA-ruled territories in the West Bank are a whole different world. The post-Oslo period can be divided into four phases: The first is rapid growth and prosperity up until 2001. Remember the mass trips to the Jericho casino and the shopping sprees of Israelis in the markets of Palestinian cities near the Green Line? Then, two years of Intifada brutally erased all these achievements. However, since then and up to this day, the Palestinians managed to maintain a surprising economic miracle.

9 View gallery

Palestinian laborers cross the border to the Gaza Strip after a day's work in Israel

(Photo: Nadav Eves)

For the Palestinians in the West Bank, the past 20 years have been marked by growth, improved standard of living, notable advances in economic governance, hesitant but continuous inflow of foreign investment and a constant civil struggle against Israeli restrictions and blockades.

The per capita income increased by 8.5% annually, far exceeding any realistic projections. The statistical outcome: a significant reduction in the income gap per capita compared to Israel (4.5 times lower when adjusted for purchasing power).

STILL NO PEACE THREE DECADES AFTER HISTORIC AGREEMENT

(ILTV)

According to the data, the total aid to the PA in the past 20 years amounted to $40 billion. Every Palestinian household in the West Bank has a mobile phone (though only 3G, not 4G or 5G), a refrigerator, and a TV satellite dish on the roof. Seventy percent have a desktop or laptop computer, 90% have home Internet and about a third own a private car. A quarter million young Palestinians are pursuing higher education at universities, and another 15,000 are enrolled in community colleges.

On the other hand, only 77% of men and 16% of women participate in the workforce. Unemployment, despite employment opportunities in Israel, remains in the double digits at 12%. Exports to Israel and Jordan are marginal, the trade deficit is very high and the budgetary challenges intensify as Israel, for policy and security reasons, delays the transfer of funds it owes to the Palestinians under the Paris Protocol.

I've had numerous conversations with veteran Palestinian economists. They continue to dream of having full control over their economic fate and hope it will come to fruition. "You've taken over our economy," they told me with bitterness.

9 View gallery

Palestinian merchant selling bagels to Palestinians crossing to work in Israel

(Photo: Reuters)

"Why shouldn't we also benefit from the mineral riches of the Dead Sea, from its Palestinian portion?" they ask. "Why not develop agriculture together with you in the Jordan Valley, where most of its lands are untapped? And what happened to the foundational principle of free movement of people, capital and initiatives, as promised in the Paris Protocol?" This isn't how they envisioned the Palestinian economy to be in three decades.

We Israelis also didn't imagine that after three decades we would still be so far from realizing the principles outlined in the distant Oslo Accords.

A 3:3:3 economy

According to a new social survey by the Central Bureau of Statistics, half of Israelis aged 20 and over believe that the media portrays the reality in Israel as "worse than it actually is." This half now also includes also a top economist - Prof. Eytan Sheshinski (who is soon to be awarded the Israel Prize for his lifetime achievements).

In an interview with KAN BET Radio last week, he said, "The economic press paints a bleaker picture than reality. The economy is not in the crisis that the pessimists predicted. I'm surprised at myself for saying this."

Sever PlockerPhoto: Ori Davidovich, Nitsan Dror

Sever PlockerPhoto: Ori Davidovich, Nitsan DrorSheshinski shared his assessment before the release of data indicating an annual inflation rate of 3.3% in July, a real growth rate of 3% in the second quarter of the year and a 3.4% unemployment rate. It appears that the economy is converging on the magic number 3. When compared globally, this figure seems even more impressive.

So why has the shekel weakened? After all, the difference between imports and exports, or trade deficit, has shrunk by 20% in just six months, the international balance sheet shows a surplus of around $20 billion this year and foreign currency reserves have reached new highs.

So how, how, how then is the dollar appreciating in a country with such forex reserves? As per the late Jewish-American economist and Nobel Prize laureate Prof. Paul Samuelson, there are three things that drive people mad - seeking respect, greed and trying to understand the financial markets. In other words, don't even try.