Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

As Israel heads to elections next week, one of the biggest questions is how voting patterns will look in the ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, community.

After a year in the opposition the Haredi parties are traumatized, and eager to gain back power and sit in the next coalition government. For Haredi society, the upcoming election likely will showcase the very slight, yet dramatic changes it is going through.

The ultra-Orthodox sector makes up about 13% of Israel’s population and is its fastest-growing one. An average Haredi family has at least four children. The poverty rate is higher than the average rate, with many families struggling to make ends meet. Most Haredi families rely on just one income.

According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics and the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research at the Israeli Democracy Institute (IDI), in the previous elections in March 2021, the majority of Haredi Jews voted for ultra-Orthodox parties.

Just over 10% voted for other parties, with the overwhelming majority of them voting for parties in the right-wing bloc, led by former Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

The number of Haredi parliament seats has fluctuated slightly throughout the years, with the parties gaining significant political power due to the nature of coalition politics in Israel. This has attracted criticism from opponents who say the Haredi sector’s accumulated power is much larger than its proportion of the population.

The two main Haredi parties are United Torah Judaism and Shas. Both see themselves as part of the right-wing bloc and have been part of all governments led by Netanyahu before he stepped down last year.

IDI data shows almost 80% of eligible Haredi voters showed up at the polls last March. There is concern that next week the numbers will drop.

Within the Haredi community, there seems to be declining trust in the leadership of the parties. This could change the dispersal of the vote.

There are more and more voices within the community saying that they will vote for the ultra-nationalist Religious Zionism list led by Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir.

“The Haredi public has become more nationalist in recent years,” said Moshe Morgenstern, an attorney and a member of the Bnei Brak municipal council, which is home to the second-largest Haredi population in the country. “Ben-Gvir exudes a feeling of safety for many,” he added.

“We might not see a drastic change, but as a trend, this is very significant,” said Yitzik Crombie, a Haredi entrepreneur who promotes the sector’s employment in the high-tech sector.

The Religious Zionism alliance is polling consistently as the third-largest party. Ben-Gvir’s appeal has made him a significant player in the Haredi discourse.

“It is a protest against the Haredi parties,” explained Shoshi Shtub, a political consultant who is a Haredi Jew. “Ben-Gvir promises to uphold Jewish values while keeping the vote within the right-wing bloc.”

In recent years, the Haredi population has undergone major changes. The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic raised questions about the movement’s future in terms of education and Haredi assimilation into wider parts of Israeli society.

“The younger, more modern and less conservative Haredis feel somewhat disconnected from the Haredi parties. They feel their interests are not being promoted,” Crombie said.

The outgoing government is seen by many in the community as the most hostile toward ultra-Orthodox Jews. Current Prime Minister Yair Lapid leads the centrist Yesh Atid party, which has often campaigned against core issues of concern to the Haredim.

When Lapid entered politics, his main goal was to decrease the political influence of ultra-Orthodox Jews. He favors lifting their blanket draft exemptions from military service and wants to limit the authority of the Haredi-dominated Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

Lapid’s arrival on the political scene in 2012 marked the beginning of a poignant battle between secular and religious Jews in Israel. For the Haredi sector, Lapid is the symbol of the secular struggle against their way of life. For Netanyahu, he is his main political rival. In many ways, this political rivalry is about the future identity of Israel as a Jewish state.

In the last year, Lapid governed with Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman. Liberman is considered an archrival of the Haredi community who once said he wished to put them in wheelbarrows “straight to the dumpster.” Together with Lapid, Liberman tried to promote policies that have been perceived by the ultra-Orthodox as targeting their very existence.

“We went through a very, very tough year,” said Morgenstern. “Some of the laws were directed primarily at the Haredi community.”

A law that denied daycare subsidies for one-income families did not pass. Increased taxation on disposable goods and sweet drinks frequently and widely used by Haredi families, especially on the Sabbath, did pass and had a direct impact on Haredi wallets.

A feeling of near-persecution might instinctively lead anyone, including the Haredim, to vote in larger numbers.

Lapid has since softened his tone toward the Haredi community, perhaps realizing the political toll such a position could take on him and his party.

“The Haredi vote will never go to the left bloc,” said Bar-Ilan University professor Asher Cohen, an expert on religious parties and voters. “They will never sit with Liberman or Lapid; the political price for the Haredi parties is too high.”

While the political leaders of the Haredi Jewish community have made statements indicating they may consider giving their mandates to someone other than Netanyahu, they have categorically ruled out Lapid and Liberman.

“These elections are about the Jewish identity of the state,” said Morgenstern. “The left does not differentiate between political and social leftist policies. The right-wing bloc is more aligned with Haredi values. In choosing to (ignore) liberal values, the Haredi public cannot accept the left.”

Left-center parties that promote issues like public transportation on the Sabbath (when observant Jews are not permitted to drive) or flexibility on conversion and kosher food have alienated religious voters.

In the past, there have been coalition governments with left and Haredi parties, but in recent decades, this has become increasingly unlikely.

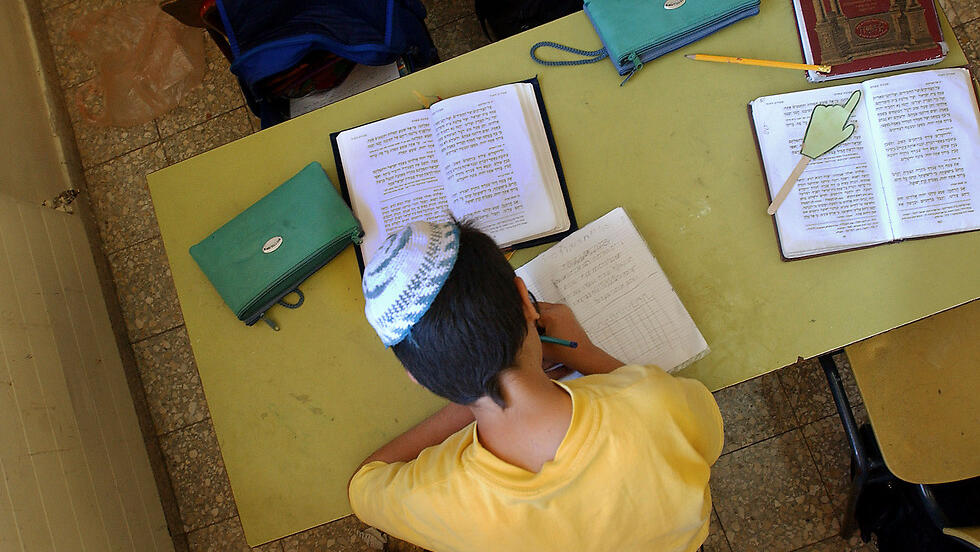

Perhaps the most pressing issue on the table is that of education.

“It is the most sensitive issue in the Haredi world,” said Cohen.

The debate on whether to impose core curriculum studies of math and English has ramifications on the future of the Haredi population and its ability to enter the Israeli workforce.

“People want representatives who promote the education of Jewish values, but also an education that prepares children for the labor market and helps them enter the economy and academia,” said Crombie, “All the while, they still want to safeguard the Jewish identity of the state and preserve the status of those who engage in religious studies. This combination makes some of them identify less with the Haredi parties.”

The reality of a high cost of living has led a greater number of Haredi Jews to enter the workforce. This has very gradually begun to erode the isolationism which has characterized their society for decades and has been zealously safeguarded.

This is cause for concern for both religious and political leaders in the ultra-Orthodox world. Their political power also is threatened as the vote may spread out among more parties.

The dent in the isolationism has led to a greater identification with the state of Israel among some in the Haredi community.

“The youngsters have undergone ‘Israelization’ and they are much more right-wing and nationalist,” said Cohen.

This also changes other priorities.

“People are concerned with their daily lives – housing, education, high cost of living. Issues of religion and state are not what they vote for,” said Shtub. In the long term, such a mindset could be revolutionary. Meanwhile, Shtub believes Ben-Gvir has become a significant player in Haredi political discourse.

“The more they feel integrated, they feel more Israeli. This means they are concerned with other matters and not only about Jewish values,” said Crombie. “The Haredi parties are not trying to face this dilemma.”

This likely will translate into a change in Haredi voting patterns.

“They are becoming much more Israeli than we think,” said Cohen.

The light undercurrents expected in the coming elections could develop into larger waves in the future, changing the political map in Israel and society as a whole.