Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Israeli and Palestinian public figures have drawn up a new proposal for a two-state confederation that they hope will offer a way forward after a decade-long stalemate in Mideast peace efforts.

The plan includes several controversial proposals, and it’s unclear if it has any support among leaders on either side. However, it could help shape the debate over the conflict, and will be presented to a senior U.S. official and the U.N. secretary general this week.

6 View gallery

The Palace of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, home of the UN Human Rights Council

(Photo: Courtesy)

The plan calls for an independent state of Palestine in most of the West Bank, Gaza and east Jerusalem, territories Israel seized in the 1967 Six Day war. Israel and Palestine would have separate governments but coordinate at a very high level on security, infrastructure and other issues that affect both populations.

The plan would allow the nearly 500,000 Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank to remain there, with large settlements near the border annexed to Israel in a one-to-one land swap.

Settlers living deep inside the West Bank would be given the option of relocating or becoming permanent residents in the state of Palestine. The same number of Palestinians — likely refugees from the 1948 war — would be allowed to relocate to Israel as citizens of Palestine with permanent residency in Israel.

6 View gallery

Aerial view shows a Palestinian village, left, and a settlement, right, separated by the partition wall on the West Bank

(Photo: AP)

The initiative is largely based on the Geneva Accord, a detailed, comprehensive peace plan drawn up in 2003 by prominent Israelis and Palestinians, including former officials. The nearly 100-page confederation plan includes new, detailed recommendations for how to address core issues.

Yossi Beilin, a former senior Israeli official and peace negotiator who co-founded the Geneva Initiative, said that by taking the mass evacuation of settlers off the table, the plan could be more amenable to them.

Israel’s political system is dominated by the settlers and their supporters, who view the West Bank as the biblical and historical heartland of the Jewish people and an integral part of Israel.

The Palestinians view the settlements as the main obstacle to peace, and most of the international community consider them illegal. The settlers living deep inside the West Bank — who would likely end up within the borders of a future Palestinian state — are radical and tend to oppose any territorial partition.

6 View gallery

Masked Jewish settlers clash with Palestinians in the West Bank village of Assira al-Kibliya, 2011

(Photo: AP)

“We believe that if there is no threat of confrontations with the settlers it would be much easier for those who want to have a two-state solution,” Beilin said. The idea has been discussed before, but he said a confederation would make it more “feasible.”

Numerous disputes still remain, including security, freedom of movement and perhaps most critically, after years of violence and failed negotiations, lack of trust.

The Foreign Ministry and the Palestinian Authority declined to comment.

The main Palestinian figure behind the initiative is Hiba Husseini, a former legal adviser to the Palestinian negotiating team going back to 1994, who hails from a prominent Jerusalem family.

She acknowledged that the proposal regarding the settlers is “very controversial” but said the overall plan would fulfill the Palestinians’ core aspiration for a state of their own.

“It’s not going to be easy,” she added. “To achieve statehood and to achieve the desired right of self-determination that we have been working on — since 1948, really — we have to make some compromises.”

Thorny issues like the conflicting claims to Jerusalem, final borders and the fate of Palestinian refugees could be easier to address by two states in the context of a confederation, rather than the traditional approach of trying to work out all the details ahead of a final agreement.

“We’re reversing the process and starting with recognition,” Husseini said.

It’s been nearly three decades since Israeli and Palestinian leaders gathered on the White House lawn to sign the Oslo accords, launching the peace process.

Several rounds of talks over the years, punctuated by outbursts of violence, failed to yield a final agreement, and there have been no serious or substantive negotiations in more than a decade.

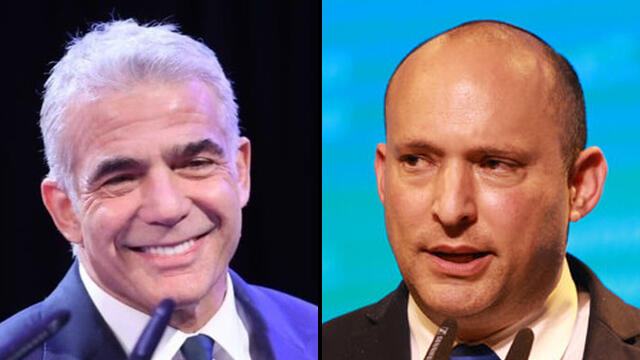

Israel’s current prime minister, Naftali Bennett, is a former settler leader opposed to Palestinian statehood. Foreign Minister Yair Lapid, who is set to take over as prime minister in 2023 under a rotation agreement, supports an eventual two-state solution.

But neither is likely to be able to launch any major initiatives because they head a narrow coalition spanning the political spectrum from hardline nationalist factions to a small Arab party.

On the Palestinian side, President Mahmoud Abbas’ authority is confined to parts of the occupied West Bank, with the Islamic militant group Hamas — which doesn’t accept Israel’s existence — ruling Gaza. Abbas’ presidential term expired in 2009 and his popularity has plummeted in recent years, meaning he is unlikely to be able to make any historic compromises.

The idea of the two-state solution was to give the Palestinians an independent state, while allowing Israel to exist as a democracy with a strong Jewish majority. Israel’s continued expansion of settlements, the absence of any peace process and repeated rounds of violence, however, have greatly complicated hopes of partitioning the land.

The international community still views a two-state solution as the only realistic way to resolve the conflict.

But the ground is shifting, particularly among young Palestinians, who increasingly view the conflict as a struggle for equal rights under what they — and three prominent human rights groups — say is an apartheid regime.

6 View gallery

Demonstrators hold Palestinian flags as IDF soldiers stand guard during a protest against Israeli settlements in Masafer Yatta

(Photo: Reuters)

Israel vehemently rejects those allegations, viewing them as an anti-Semitic attack on its right to exist. Lapid has suggested that reviving a political process with the Palestinians would help Israel resist any efforts to brand it an apartheid state in world bodies.

Next week, Beilin and Husseini will present their plan to U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. Beilin says they have already shared drafts with Israeli and Palestinian officials.

Beilin said he sent it to people who he knew would not reject it out of hand. “Nobody rejected it. It doesn’t mean that they embrace it.”

“I didn’t send it to Hamas,” he added, joking. “I don’t know their address.”