If the missile fired last Wednesday by Hezbollah at an advanced IDF drone in the skies over southern Lebanon had indeed hit it and brought it down, would the political echelon in Israel have instructed the military to attack Lebanon in response?

The probable answer is yes, for this was unlike the lower tech drone that crashed along the Lebanon border on Monday and which Hezbollah claimed to have brought down.

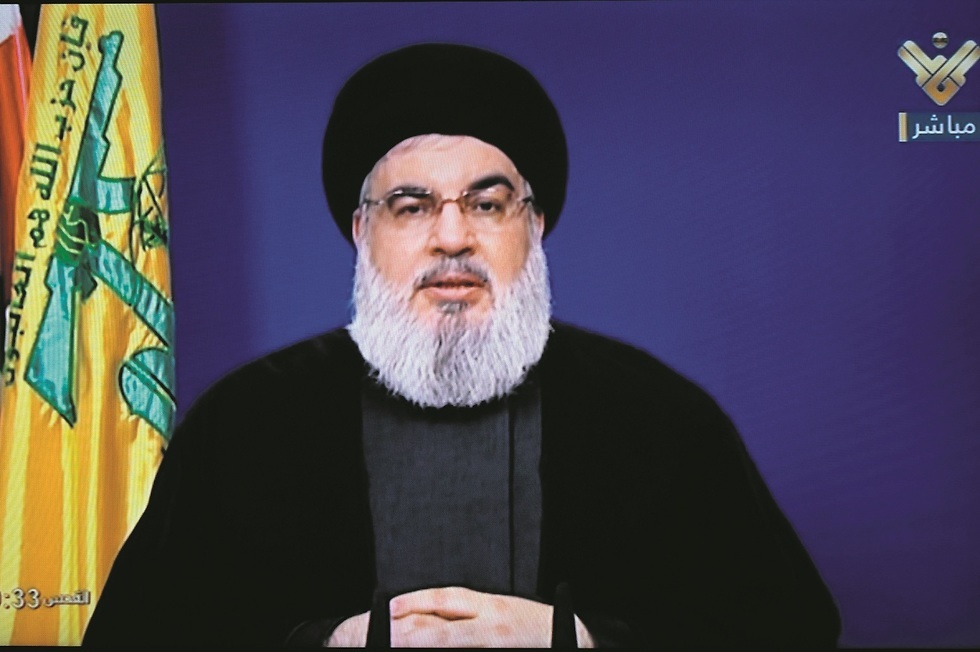

4 View gallery

The IDF drone Hezbollah claimed to have brought down along the Lebanon border on Monday

Last Wednesday, the Israeli Air Force would have struck the anti-aircraft battery responsible or similar Hezbollah targets, and the northern border could have erupted into heavy exchanges of fire.

Worse still, Hezbollah knew that if it succeeded in felling the drone, Jerusalem would definitely respond, and intended to remind Israel that the "quiet border" in the north is the most explosive and easiest to ignite.

Qatar has delivered Israel an industrial peace on the Gaza border. The country has increased the aid it has committed to provide to the Hamas government from $240 million in 2020 to $360 million in 2021.

As such, there is a form of control along the southern border. But the Lebanon near miss is a reminder that Israel is sitting on a mountain of explosives to the north.

It is fair to assume that neither Israel nor Hezbollah has any real interest in igniting the frontier.

The two sides apparently have a mutual deterrence: Hezbollah acts against Israel in a restrained and measured manner and Israel makes a supreme effort not to harm Hezbollah members and does not openly attack the organization's military capabilities in Lebanon.

But this only works until someone decides to cross the line.

The Israeli Air Force flew over Lebanon as part of preparations for a violent, unpredicted eruption from a country that does not have an effective central government.

This requires Israel to have maximum intelligence control, including a presence in the air. But Hezbollah sees itself as the defender of Lebanon, and as such Israeli overflights are a violation of national sovereignty.

In truth, neither side abides by the agreement reached at the end of the 2006 Second Lebanon War as part of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1701.

The situation could explode as soon as one of the parties decides it is not playing the game anymore. And it almost happened last week.

In the 24 hours leading up to the missile fire on the IDF drone, the Lebanese media reported an unusually large number of Israeli fighter jets and UAVs.

The flights were reported in the southern suburbs of the capital controlled by Hezbollah and over Ras al-Ain and Tyre, close to the Israeli border.

It is possible that these flights were a response to Hezbollah's unusual activity - but while this was all happening, the missile was launched.

A missile was also fired at IDF drone last November, but this time Israel confirmed the Lebanese reports of the shooting, as it took place in broad daylight and was recorded.

And thus on one clear day, without warning and on the eve of an election and all that that implies, Israel might easily have found itself - just as it did in 2006 - in the throes of an armed conflict in the north.