The first liberal rabbi in the Knesset, Gilad Kariv from the Labor party, has his sights set on ending the monopoly of the ultra-Orthodox on many aspects of everyday life in the Jewish state.

The conservative line of the Jewish religion - laid down by ultra-Orthodox rabbis during the foundation of Israel in 1948 - dictates that Israeli Jews need the services of Orthodox rabbis to marry or divorce, that public transport grinds to a halt on the Sabbath, and that religious dietary laws apply in all public institutions, including the army and schools.

"The only subject on which people of the right and the left agree by a great majority is the relationship between religion and the state," said Kariv.

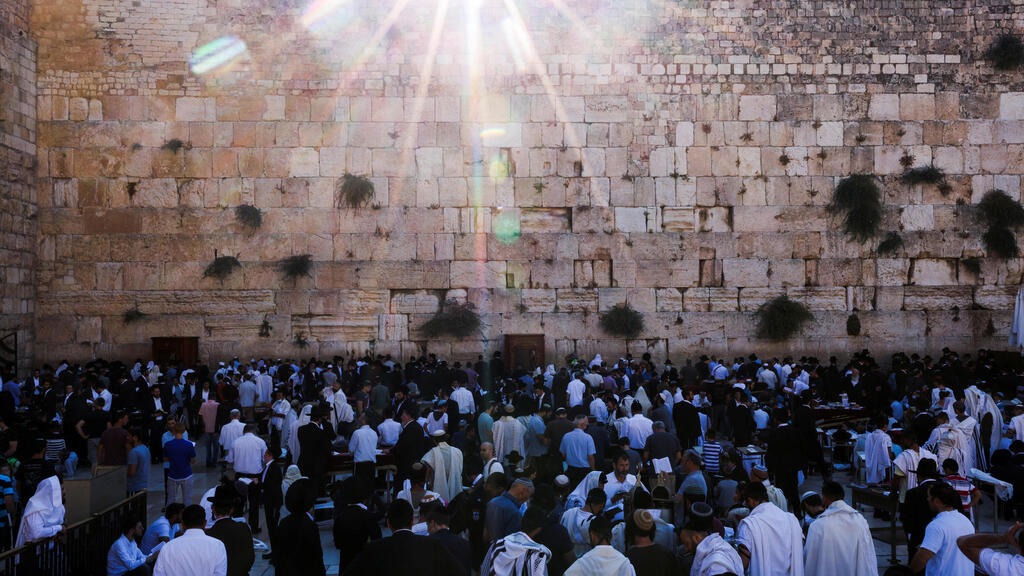

"Most Israelis are in favor of civil marriage, and public transport on the Sabbath (the Jewish day of rest and prayer)," said Kariv, adding that most Israelis are also in favor of mixed space for prayers at Jerusalem's Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism.

But 48-year-old Kariv, who was elected in Israel's last polls in March has a liberal agenda.

In the United States, which is home to the largest number of Jews after Israel, most adherents follow liberal or conservative schools of Judaism, both of them non-Orthodox and advocating equality between the sexes.

Although they form a minority in Israel, Kariv believes "most of the country's non-religious public feel much closer to us (liberals) than to Orthodox Judaism".

For Kariv, a trained lawyer and leading light in Israel's religious liberal camp for more than a decade before running for parliament, the country is "Jewish and democratic, which is not the same thing as Orthodox and democratic".

At first, Orthodox colleagues in the Knesset refused to acknowledge him, and some still boycott any debate if the "Satanic" deputy takes part.

3 View gallery

Prime Minister Naftali Bennett's multi-party government at the Knesset plenum

(Photo: Yoav Dudkevitch)

In 2016, progressive movements were behind the authorization of an area at the Western Wall for men and women to pray together, but former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu scuttled the plan under pressure from ultra-Orthodox coalition partners.

The plan is now back on the agenda of Israel's new government, to the fury of the ultra-Orthodox.

Moves toward religious pluralism "correspond to the spirit of the government, with its wide and varied coalition", Kariv said, referring to Prime Minister Naftali Bennett's multi-party government.