Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The brothers didn’t have a chance to say goodbye. As young Polish Jews, each came out of World War II with scars that forever shaped how they viewed the world, and each other. One survived Auschwitz, a death march and starvation. The other endured cold and hunger in a Siberian labor camp, then nearly died in a pogrom back in Poland.

Alexander and Joseph Feingold chose New York City as the place to start over. It is where they became architects, lived blocks from each other and lost their wives days apart. It was there that they died four weeks apart, each alone, as the coronavirus pandemic gripped the city.

7 View gallery

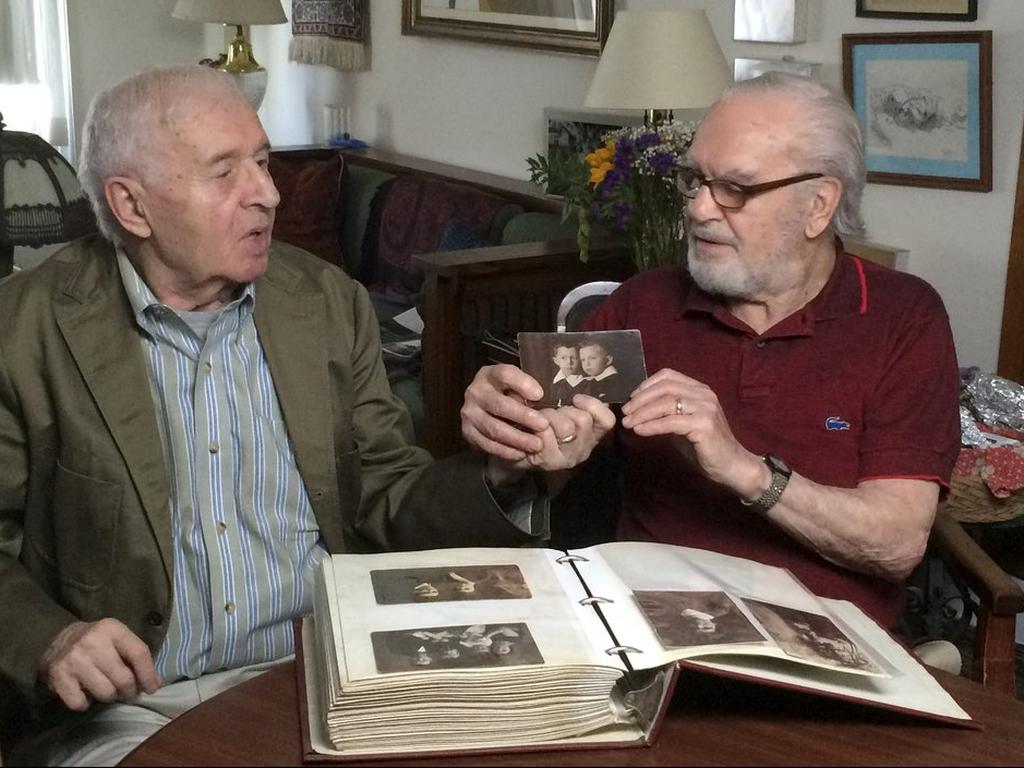

Brothers Alexander Feingold, left, and Joseph Feingold look at photo of themselves as boys in Joseph's apartment in New York

(Photo: AP)

Joe, 97, died April 15 of complications of COVID-19 at the same hospital where Alex, 95, succumbed to pneumonia on March 17.

Joseph Feingold never escaped the guilt of leaving his mother and two younger brothers to escape the Nazis.

When Alexander fell ill, Joseph called his stepdaughter from his assisted living facility and asked her to take him to his brother.

“Joe was wanting to go sit with Alex, to say goodbye and I think, too, to make amends,” Ame Gilbert recalled. “It broke me up having to say no, and having to explain to him that no one could visit because of the virus.”

The siblings were childhood rivals, separated in age by only 18 months. As little boys playing in Warsaw, they pretended to be Native Americans. Firstborn Joe always got to be chief, he recalled in a memoir.

Their youth was shattered when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939 and the Soviet Union seized Poland’s eastern half two weeks later. World War II had started. Joe was 16 and Alex not yet 15.

By the time they were in their early 20s, both brothers had witnessed the horrors of war. But only one bore a concentration camp tattoo on his arm. Joe had been the luckier of the two. Both brothers knew it.

Joe and their father, Aron, who was threatened with arrest by the Gestapo, fled to the Soviet-occupied part of Poland. They were eventually arrested and sent to separate labor camps in Siberia. Conditions were harsh but improved later in the war and father and son were reunited.

Back in German-occupied Poland, Alex was forced into the Kielce ghetto with his mother, Ruchele, and youngest brother, Henryk. One night, Nazi SS officers forced him and other male Jews into a field with shovels.

Alex thought he was digging his own grave. Instead, wagons unloaded hundreds of bodies, and the Germans ordered the terrified group with the shovels to search the dead for valuables. Alex used a bottle to knock gold fillings from teeth and buried bodies, going numb as the awful ritual repeated.

Ruchele and 13-year-old Henryk were deported to the Treblinka death camp. Alex ended up at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he saw corpses burned outside the gas chambers. He helped dismantle Allied bombs at the Buna subcamp in exchange for tobacco and extra food.

In January 1945, as the Soviets moved west, Alex was evacuated in a death march to Bergen-Belsen, the concentration camp where he was liberated on April 15. He was sick with dysentery and weighed just 88 pounds (40 kilos).

After the war, Joe and his father returned to Poland, where 90 percent of the country’s 3.3 million Jews perished in the Holocaust. Seeking information about the family’s fate, Joe returned to Kielce and was beaten unconscious and left for dead in the most deadly attack on Jews in postwar Poland.

7 View gallery

Mourners crowd around long a narrow trench as coffins of victims of an anti-Semitic massacre are placed in a common grave following mass burial service, in Kielce, Poland; the July 4, 1946, massacre killed 42 people, most of them Jews, and wounded over 80

(Photo: AP)

Joseph Feingold was believed to be the last living survivor of that 1946 massacre, according to historian Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, author of “Cursed: A Social Portrait of the Kielce Pogrom.”

Joe and his father finally saw Alex again at a displaced person’s camp in Germany 19 months after the war ended. In an oral history with the USC Shoah Foundation, Alex recalled the reunion as a “sad moment.”

“I was so cold, unemotional — very, very cold and unemotional,” he recalled. Fearing a breakdown, he couldn’t bring himself to speak about seeing his mother and Henryk for the last time — not then, not ever.

Even without hearing it from his brother, Joe knew the shape of the horror.

7 View gallery

Joseph Feingold and his wife Regina at their country house in Ghent, New York

(Photo: AP)

“The feelings of guilt that I have, which I cannot overcome, are still with me,” he wrote in a memoir. “Alex never reproached me for being abandoned by his father, or by his older brother, or for anything else that he had to live through and survive. He didn’t reproach me, but he didn’t have to.”

Alex’s trauma, according to Mark Feingold, the second of his own three sons, caused indelible injury and “made him less capable of being involved and recognized in society” than Joe.

Joe gained public recognition with the donation of a violin to a girls’ school in the Bronx, featured in an Oscar-nominated 2016 documentary, “Joe’s Violin.” In the key scene, the 12-year-old girl who receives the instrument, Brianna Perez, plays Joseph a Yiddish song his mother loved.

7 View gallery

Brianna Perez, a Bronx schoolgirl, hugs Joseph Feingold at the Bronx Global Learning Institute for Girls in the Bronx, New York

(Photo: AP)

His stepdaughter says that while warm and generous, Joe had his own reservoirs of unfathomable pain that revealed themselves as anger and impatience, and he was haunted by frequent nightmares.

When Mark Feingold took his father to Mt. Sinai West Hospital in March, doctors assumed Alex had COVID-19. He tested negative, but the pandemic overshadowed his last days. A visit from Joe might have brought some comfort.

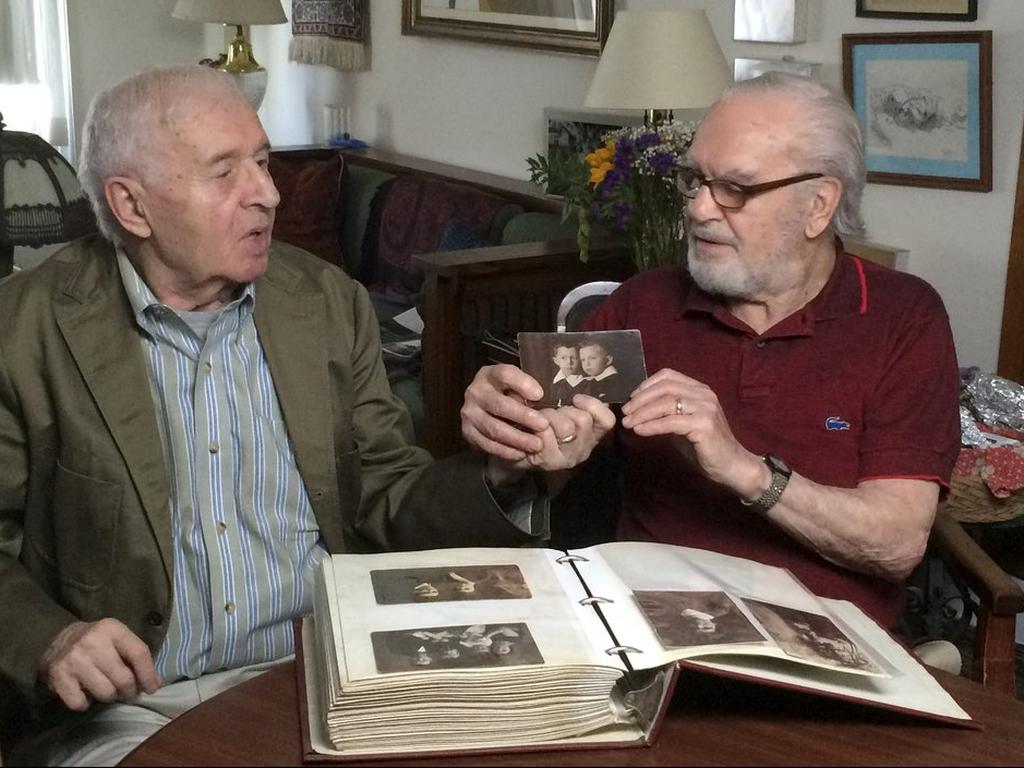

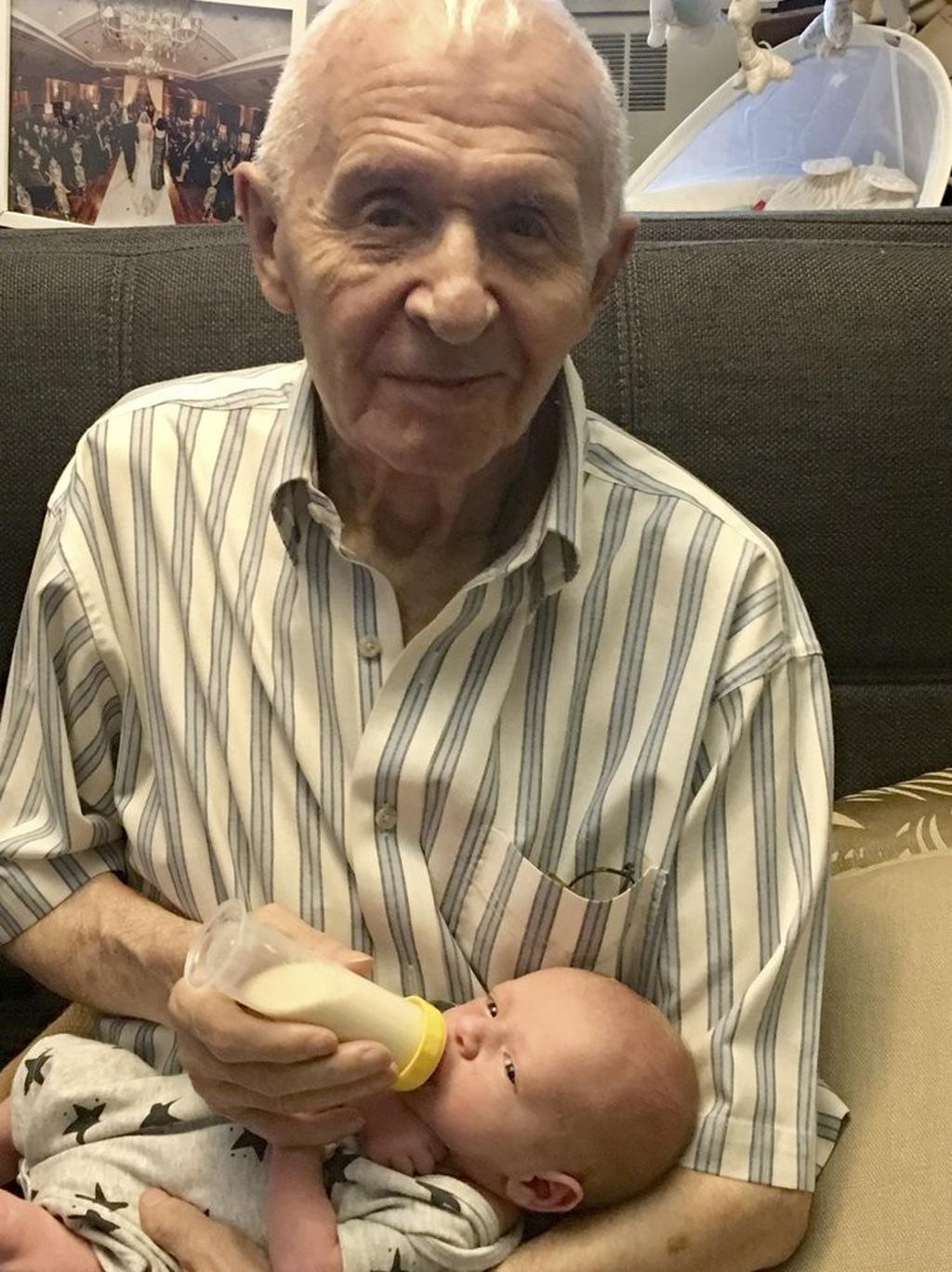

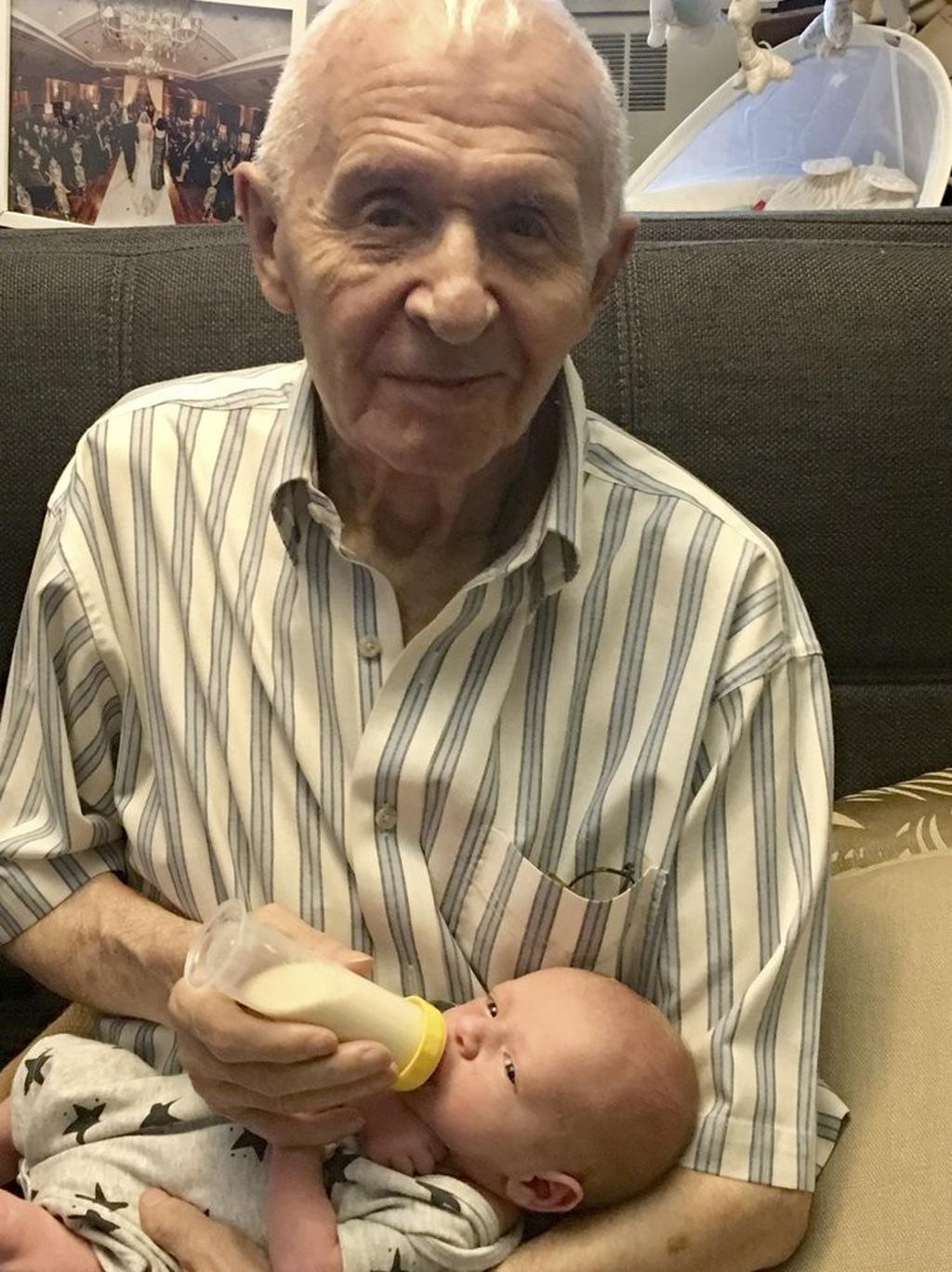

7 View gallery

Alexander Feingold holds his first grandchild Dylan at his home in New York

(Photo: AP)

Shortly before his own death, Joseph dreamed he was in the gas chamber with his mother and Henryk, according to Gilbert, his stepdaughter.

“When Alex died and he didn’t have a chance to make peace with him, I thought ‘Oh, Joe’s going to die soon.’”

Joe’s eyes were closed as Gilbert said goodbye in a video call.

“I am choosing to believe that he heard that I loved him. I went through the list of all of those who loved him,” Gilbert said. “Hopefully, that gave him comfort.”