Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

For those raised on a steady diet of Judge Judy and reruns of Law & Order, few things are more unsettling than a letter in the mail that reads: “You are summoned.” This meant I had been called to fulfill my civic duty as a juror.

My mind raced with dramatic visions of jury room debates where I’d passionately argue, like Olivia Pope, to convince everyone that O.J. was guilty. Reality would hit me soon enough, but in the meantime, nothing was stopping me from Googling court dates for P. Diddy or scouring for new lawsuits against Donald Trump that might coincide with my summons. Who knows? Maybe I’d land on a high-profile case.

Jury selection: A day at a New York courthouse

(Video: Daniel Edelson)

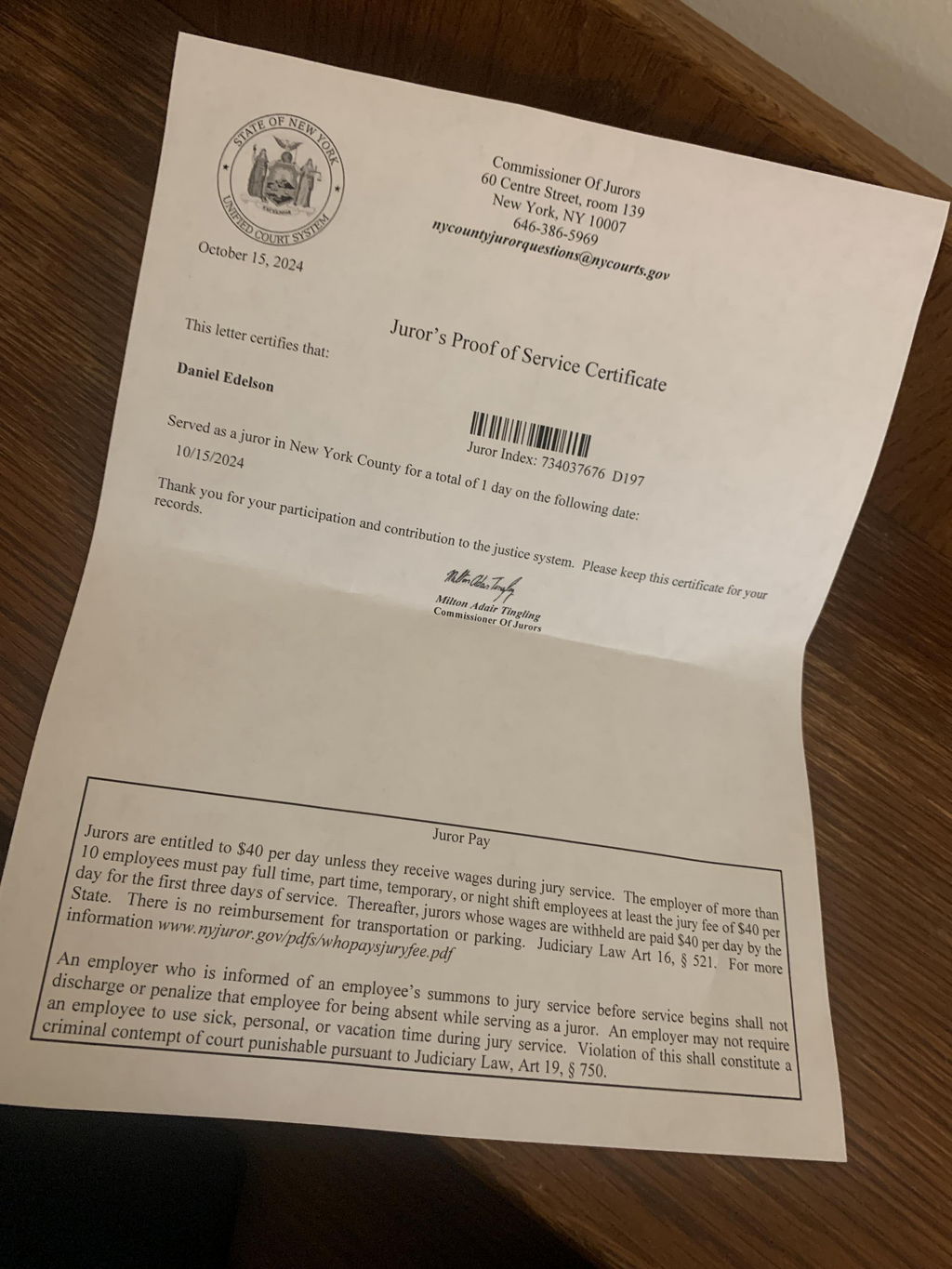

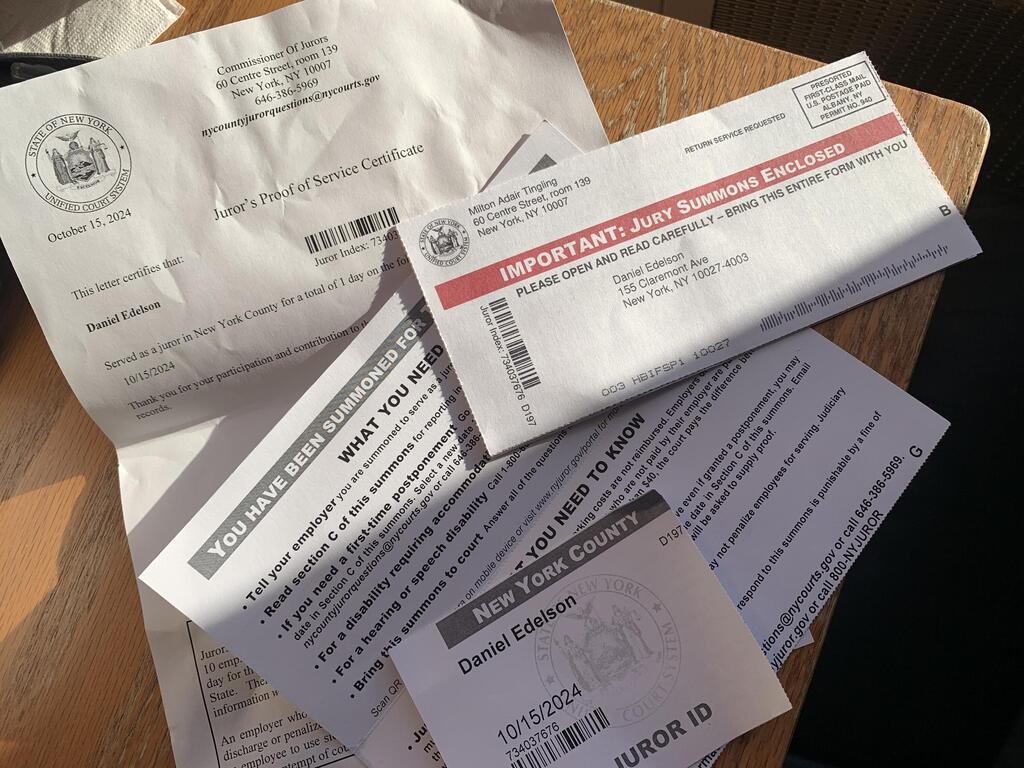

The envelope in the mail couldn’t have been more conspicuous. Americans have always had a flair for the dramatic with bells and whistles. "You Have Been Summoned for Jury Service," the bold text declared. The date fell on the eve of a holiday, and for a brief moment, I considered invoking my Judaism to get out of it. But I knew it would only delay the inevitable. New York law allows you to postpone jury duty only once. Missing the rescheduled date would label me a "non-compliant juror," subject to a hefty fine or even arrest for contempt of court.

And so, on a dark October morning, I found myself dragging out of bed before sunrise, stepping into the 48-degree chill, and navigating endless lines—from the subway entrance to the courthouse doors in Chinatown. Behind me stood a frazzled mom, who, in a distinctly un-New York, non-progressive Southern drawl, threatened to smack her crying baby if he didn’t stop. As would become a recurring theme, he probably didn’t want to be there any more than I did.

Inside the courthouse, the same story continued: another line for the elevator, a never-ending line to the 11th floor, and yet another line outside the room where I was supposed to serve as a juror. The room was packed with dozens of people, most of whom looked tired, annoyed and not entirely sure why they were there. I joined the line without question—a distinctly American habit.

5 View gallery

Daniel Edelson at the entrance to the jurors assembly room at the courthouse

(Photo: Courtesy)

After about 15 minutes, someone finally voiced the absurd question: “Is this the line for jury duty?” It turned out I’d been standing in the wrong line entirely—this one was for exemptions, where people were trying to get out of serving.

I’d thought people would jump at the chance to judge others. After all, we do it recreationally all the time—so why not earn $40 a day for it? But apparently, the idea doesn’t appeal to most. In a way, it was a relief to discover that beneath the saccharine American veneer lies a more honest truth: an individualistic, solidarity-free society doesn’t suddenly change its stripes over a fancy envelope in the mail.

When presidential candidates openly call to dismantle already-weak public health care systems and deport the vulnerable and the foreign-born, is it any wonder that when told, “Hey, without your presence, justice won’t be served,” they’re not exactly rushing to comply?

Many Americans go to great lengths to avoid jury duty, sometimes in particularly creative ways. Some show up in expensive suits to appear "too important" for the role, while others wear rags to convey the opposite impression. If they hear it’s a traffic case, they might suddenly declare, “When I was five, my dad jaywalked, so I’m unfit to judge a case like this—sorry.”

Those who remain face a barrage of manipulation from attorneys, who often assume the jurors lack knowledge and try to confuse them with complex calculations for medical damages. Jurors might whisper to one another, “Oh, poor guy, maybe we should cut him some slack.” But typically, the judge steps in to steer the jury toward more reasonable conclusions, dropping heavy hints like, “This person broke the law and should be punished accordingly.”

For those unfamiliar with the system, it can seem odd. Would you trust your fate to the random person sitting next to you on the bus? Yet, Americans are deeply attached to their jury system (when they’re not required to participate). When told that in many countries a single judge decides cases, they tend to shift uncomfortably in their seats. What? Just one judge decides? Isn’t that strange?

asdv

The concept of a jury is admittedly quite noble. Its origins trace back to the Magna Carta—a 13th-century charter of rights that England’s King John was forced to sign, promising fair trials and ensuring that judges would not simply serve the interests of the ruling class. The United States, founded as a nation of immigrants seeking to escape Britain’s class system, naturally embraced this egalitarian principle.

Juries are a cornerstone of the American justice system and are constitutionally mandated. Some might argue the process is merely theater, with judges ultimately steering decisions, but by law, juries hold the ultimate authority and can override a judge if they choose. The Constitution guarantees a fair and swift trial before a group of “ordinary” citizens tasked with determining guilt or innocence.

In criminal cases, jurors decide whether the prosecution has proven the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. For serious cases, such as those involving the death penalty, the jury also determines the sentence. In civil trials, jurors decide whether the defendant should compensate the plaintiff and, if so, how much.

In states like New York, before criminal charges are filed, a "grand jury" convenes to decide whether there is enough evidence to proceed to trial. Those following Trump’s legal entanglements may recall that if sufficient evidence is found, the case moves to a "petit jury," which determines guilt or innocence. In some cases, a separate jury may be assembled to decide the sentence. This layered process means one thing: the system needs a lot of jurors.

Nearly every U.S. citizen over the age of 18 can be summoned for jury duty, entering a selection pool known as the "jury pool." To qualify, candidates must meet basic criteria, including citizenship, proficiency in English, good health and a clean criminal record.

Selection happens through a process called "voir dire," where prospective jurors are questioned about their background and potential biases. Those chosen may spend days, weeks or even months serving, particularly in states where juries must reach unanimous decisions. For each day of jury service, participants are entitled to $40, paid either by the state or their employer.

Interestingly, the British chose not to implement the jury system in what was then Mandatory Palestine. Fearing that local residents might acquit individuals charged with rebellion against the mandate, the British avoided introducing this extensive system. Today, it’s hard not to be struck by the enormous resources the U.S. dedicates to selecting jurors—a bureaucratic process turned into a large-scale operation. True to form, America does everything on a grand scale, even something as seemingly mundane as jury selection.

asdfdxc

A diverse crowd fills the spacious waiting room. Like New York City itself, the room is a microcosm of the world: old folk, blue-haired hipsters, suits and, above all, exhausted people nodding off in their chairs. Unlike other jurisdictions that rely solely on voter rolls, New York pulls potential jurors from a variety of databases—tax authorities, informal education records and more—aiming to reach as many people as possible and assemble the most diverse jury pool.

5 View gallery

Jury room at the courthouse: instructional videos and hours of boredom

(Photo: Daniel Edelson)

Studies show that diverse juries have a significant advantage. Groups composed of individuals from varied backgrounds tend to examine evidence more thoroughly and engage in deeper discussions before reaching decisions. By contrast, homogeneous juries can lead to less fair verdicts, particularly in cases involving defendants from minority groups. All-white juries are statistically more likely to convict Black defendants at higher rates. I know this because it was explained to us by a law professor in a video shown to all jury candidates (more on that later).

But despite the room’s visible diversity, everyone shares one common trait: no one wants to be there. I overheard one man solemnly argue to the clerk that being in a relationship made him unfit to serve. Another managed to dodge service by claiming he didn’t understand English—delivered in Spanish with a thick Yankee accent.

Those of us who stayed filled out forms about ourselves and waited. And then we waited some more. “Thank you for your service,” said the polite clerk, patiently repeating instructions for late arrivals with admirable composure. She played a video featuring the chief judge, who enthusiastically extolled the privilege of serving as a juror and ensuring justice for all. “No one can escape this duty—not even me,” he concluded.

Next came the professor’s video, with all the flair of a Hollywood production. It delved into biases and stereotypes. On-screen, dashed triangles formed a Star of David, triggering an odd sense of paranoia. The professor asked, “How many triangles are in this image?” Answers ranged from 13 to one, but the correct answer was zero—none of the triangles were complete. The point was clear: we tend to fill in gaps and supply information that may not exist. She urged us to challenge assumptions and stereotypes ingrained by media.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“Don’t let biases mislead you or discriminate based on religion, race or gender,” she said. “The system relies on you to deliver justice without prejudice. Thank you for your service!” I left with a few good insights from these videos—ones that lasted about a day.

The waiting continued until an unexpected reprieve: a lunch break. There’s no cafeteria in the courthouse, but being in the heart of Chinatown means dim sum beckons from every storefront. The $40 earned from this otherwise pointless day of waiting could easily be splurged. By 2:15 p.m., it was back to the jury room, where I claimed a desk with a charging port. The Wi-Fi was excellent, probably the highlight of the day. The supervisor asked us to maintain a “library atmosphere,” which seemed fitting given the symphony of snoring around me. I settled into a few surprisingly productive hours of work.

assfas

Serving on a jury in New York was once a dubious experience, with dirty rooms, grumpy clerks more focused on cleaning floors and talk shows blaring on televisions. But in 1994, Chief Judge Judith Kaye, the state’s highest-ranking judicial official, decided enough was enough. "We cannot ask jurors to fulfill their civic responsibility in a dilapidated environment while relying on outdated procedures," she declared. Kaye shortened the duration of jury duty, renovated courthouses, emphasized better treatment of jurors by staff and introduced stricter oversight of the racial and ethnic composition of potential juries.

In the past, attorneys could easily dismiss potential jurors based on gender, religion or other characteristics. As recently as May, widespread coverage emerged about a review of more than 35 death penalty convictions in California courts after revelations that prosecutors had manipulated jury selection. These prosecutors ensured Jewish jurors were excluded, citing surveys showing that, compared to other religious groups, Jews were less supportive of capital punishment. Jewish communities are among the most vocal opponents of execution by gas due to the Holocaust’s memory. Judges in the state admitted that excluding Jewish jurors from death penalty cases was a common practice.

My grandfather, himself a Holocaust survivor, used to recount how he was disqualified from jury service in New York, even for minor cases, out of concern that the trauma of Auschwitz would make him biased. Even today, attorneys can exclude a certain number of individuals from jury duty if they believe, for any reason, that those individuals cannot be impartial.

In a murder trial involving a shooting, for example, attorneys might ask potential jurors if they’ve lost a loved one under similar circumstances (think John Grisham’s The Runaway Jury, later adapted into a film starring Dustin Hoffman, John Cusack and Gene Hackman). In medical malpractice cases, they might ask if anyone has a doctor in their family, and so on.

In my case, I didn’t even get the chance to be screened or excluded. At 5 p.m., the clerk cleared her throat and announced that all of us, without exception, were dismissed. The room burst to life, with cheers echoing from every corner. No one understood why we’d wasted an entire day waiting only to be sent home, but no one bothered to ask. I reclaimed my freedom and bid farewell to jury duty—at least for the next two years.

First published: 22:18, 11.22.24