Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

As it confronts its most acute economic crisis in recent memory, Lebanon seems headed for disaster, with no easy way out in sight.

Faced with U.S. demands to jettison Hezbollah, the internationally designated terrorist organization, Iranian proxy and most powerful political group in the country, the Lebanese government – and Hezbollah itself – find themselves in a desperate bind.

6 View gallery

A protester holds up the Lebanese flag during a demonstration in Beirut, June 2020

(Photo: Getty Images)

“Hezbollah is facing one of its most significant challenges,” says Yoram Schweitzer, a retired lieutenant colonel in Israeli military intelligence and a former senior adviser to the prime minister.

“Going by [Hezbollah leader Hassan] Nasrallah’s recent speeches, the [people’s unrest] is what worries him most.”

Schweitzer says he believes Hezbollah’s role as the face of the government is a problem for the group.

“Hezbollah has had veto power in past governments. Nothing has really changed, but ever since [former prime minister] Saad al-Hariri was run out of office [in October 2019], the organization has had no one to hide behind. It’s the most dominant body in power, and the people know that," he says.

“[Nasrallah’s] most pressing challenge is to obscure Hezbollah’s hegemony in the country so that the protesters’ wrath won’t be directed squarely at it," Schweitzer says.

"He’s trying to shirk the blame for the economic and health crises. He’s pointing at the U.S. and saying there’s an elaborate Israeli-U.S. plot to bring Lebanon to its knees.”

The American policy of pressuring Lebanese banks to force the government to part ways with Hezbollah is taking its toll on the country’s already devastated economy.

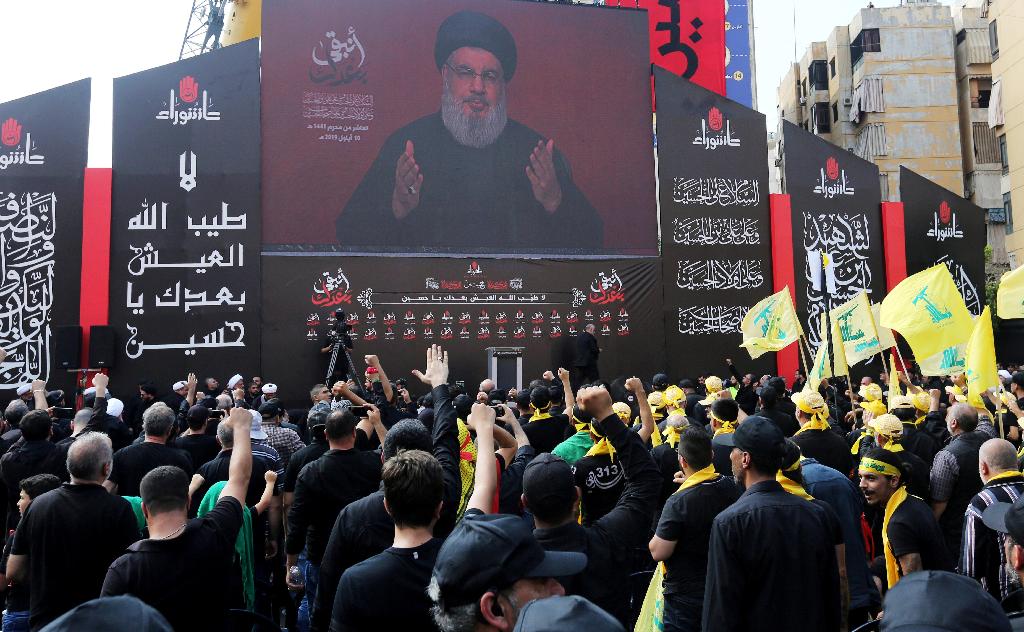

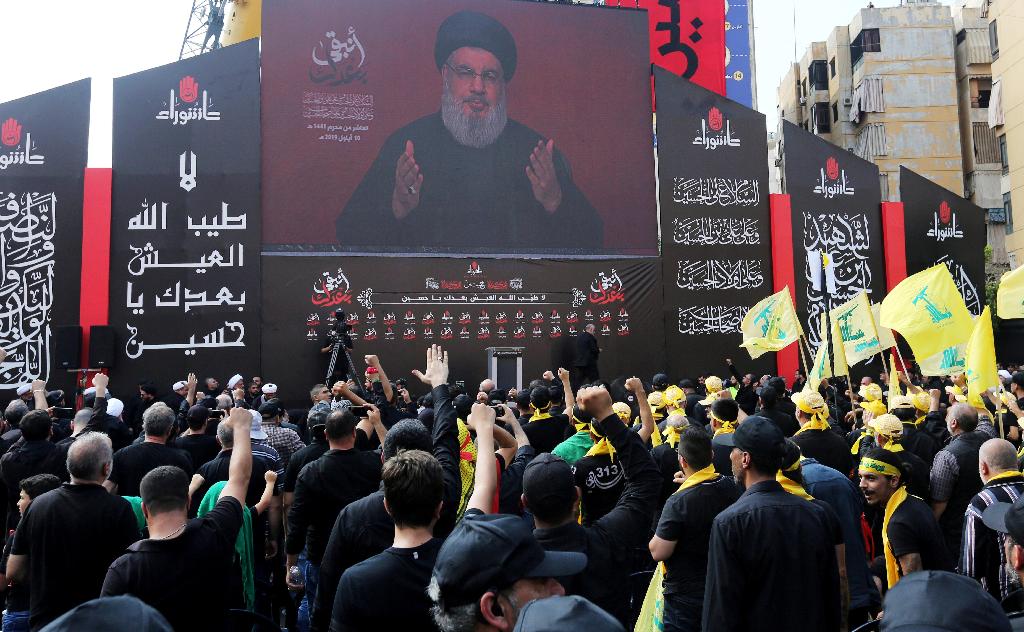

6 View gallery

Hezbollah supporters in Beirut watch a screen showing a speech by the group's leader Hassan Nasrallah

(Photo: Reuters)

The hopes of driving a wedge between Lebanon’s most powerful group and the rest of the governing parties, Schweitzer says, have never been higher.

“Obviously, there is an opportunity for the Americans here. The U.S. has chosen a strategy of maximum financial pressure combined with sanctions and isolation against both Hezbollah and Iran. It’s the centerpiece of their approach," he says.

"Hezbollah’s dire situation is, in [American] eyes, the result of their policy. They’ll try to press the advantage and offer ‘treats’ to others in Lebanon in order to pressure Hezbollah.”

Indeed, following mounting public uproar, Nasrallah in recent weeks has had to carefully reverse course on his stance regarding foreign aid.

After initially vowing to refuse all loans and grants offered through the International Monetary Fund, the Hezbollah leader walked those statements back in a speech last week, claiming Lebanon would not spurn Western offers of assistance.

“That’s probably a result of the pressure he felt from the streets,” Schweitzer says. “He de facto blinked first and sounded a more pragmatic tone. He’s changed his tune. That doesn’t mean America is not still the ‘big enemy’ for him, but the situation forced him to shift a bit.”

Still, Schweitzer doesn’t see anything resembling a collapse or an ousting of Lebanon’s strongest party.

“[Nasrallah] is still somehow managing to hold the coalition together – Christians, Shi’ites, Sunnis. They all understand that they must depend on each other, what with the mass protests.”

Shimon Shapira, a retired brigadier general who served as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s military secretary, urges caution as well.

“Hezbollah is in bad shape, but not critical,” he says. “They’ve been through internal crises in the past, financial and otherwise. The coronavirus has definitely posed a significant challenge, but with its 150,000 volunteers and operators, the organization has responded better than the official government has.”

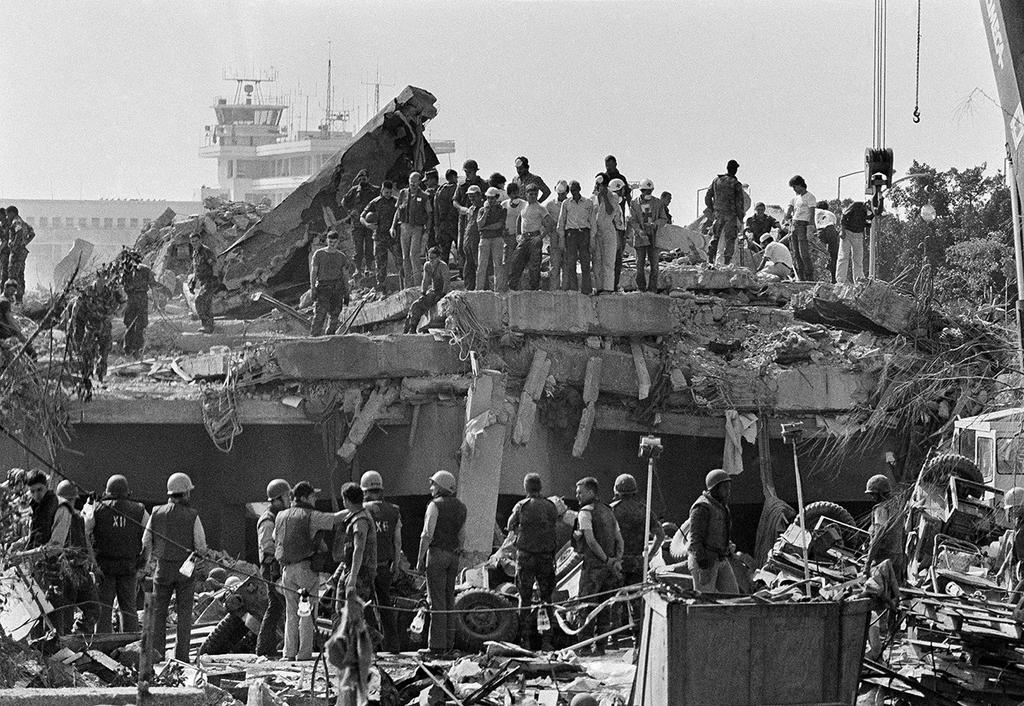

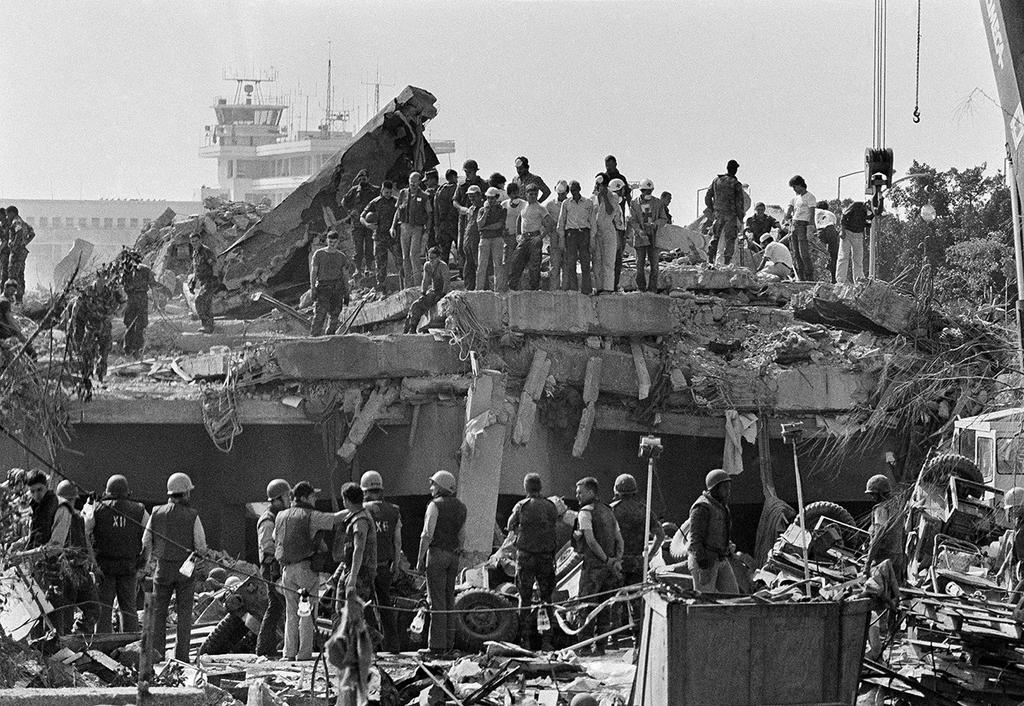

6 View gallery

Rescuers search the wreckage of the U.S. Marine command building in Beirut in October 1983, a day after 241 U.S. troops were killed

(Photo: AP)

Last weekend, Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, commander of the U.S. Central Command, visited Beirut and met with Lebanese President Michel Aoun before holding a memorial service for the 241 U.S. soldiers killed in Beirut in a 1983 bombing attributed to Hezbollah.

A statement released by the U.S. Embassy said McKenzie reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to Lebanon’s “security, stability and sovereignty.”

“The sanctions imposed by the U.S. test Hezbollah’s ability to withstand pressure,” Shapira says.

“Now is definitely a good opportunity" for weakening Hezbollah, he says. "The only thing that can threaten Hezbollah’s control of the street is rioting over money. Not enough money is being transferred from Iran, salaries have been substantially cut. Sure, Nasrallah is in a bind.

“Still, at the end of the day, there is no force right now that can really threaten [Hezbollah’s] hold on the public,” he concludes.