They called them the “Rothschilds of the East.” The Camondo family, were much more than successful bankers. They climbed to the highest social echelons everywhere they went and were highly respected within the Jewish community.

With all their money and influence, each member struggled to continue the family line. The journey came to end in 1943 with the murder of the last family member. No one is left alive. The family legacy, however, was saved by one last move.

“The last Camondo failed to continue the dynasty, but in creating his house and attributing to this house a unique soul, and persuading the country to register it in France’s artistic heritage, he managed to immortalize the names of his whole family. “

This is how Pierre Assouline in his book, “Le dernier des Camondo” (The Last of the Camondo Family), summarizes the fate of this Jewish family who, despite all their power, money and status lasting 160 years, leave no descendants but remain a glorious historical chapter - with no present and, obviously, no future.

The family story traverses the Ottoman Empire, Italy and onto aristocratic Paris where their power was greatest. Unlike other wealthy families, the Camondo family tree is remarkably sparse. Abraham Salomon Camondo was the founder of the dynasty. However, each generation, even with the threat of the family’s disappearance constantly looming over them, produced very few children.

Act I: It all started with a bank

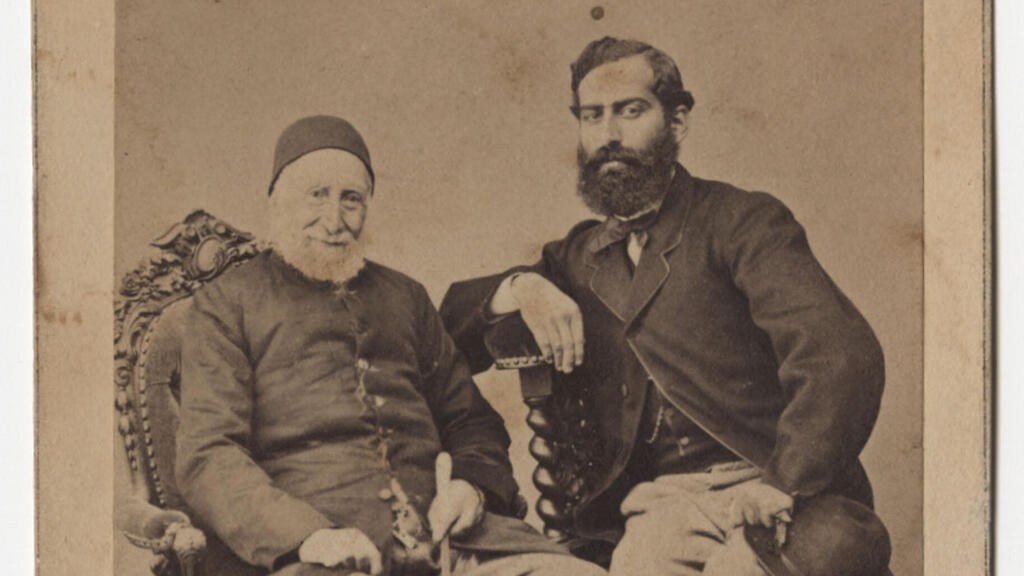

The Sephardi Camondo family settled in Kushta (Constantinople). They founded banks and took on leading roles in the local Jewish community. Estimates cite Abraham Solomon Camondo as the richest of the 200,000 Jews within the Ottoman Empire. He was banker to local government authorities and provided supplies for the Crimean War.

A possible precursor to the ultimate fate of the dynasty may be the fact that Abraham Solomon struggled to find an heir after his only son died of a stroke. Towards the end of the 19th century, management of the family’s affairs was passed onto his grandsons, Abraham-Béhor and Nissim who soon transferred their banks and businesses to Paris where the Jewish community was extremely well established.

While assimilating into the Parisian Jewish community, the duo cultivated relationships with government authorities and French society in general. Although Judaism was very much part of their identity, as they were new to Paris, they had a certain cosmopolitan air about them.

In an interview with Ynet, Pierre Assouline tells us that “the Camondo family always remained loyal to the Jewish community and were always very connected to their Judaism, regardless of their own religious practices. Within the Ottoman Empire, they belonged to the marginal, liberal camp. When they made the move to France, they were less involved in religious practice.

They nonetheless celebrated holidays, bar mitzvahs, and married within the community. Charity was a central component of their religion and identity: They were great philanthropists, coming to the aid of Jews in France and further afield.“

Act II: The heir who took control of the business

1889 was the family’s annus horribilis. Nissim and Abraham-Béhor died of pneumonia within months of one another. There were now only two members remaining to keep the family line going: Isaac, Abraham-Béhor’s son, and Nissim’s son, Moise, on whom the family had pinned their hopes. This family, with such a forceful legacy, now only had two descendants. Another precursor.

“They had to keep going at all costs” Assouline explains. “Although unmarried, they felt the ‘dynastic curse’ and took upon themselves the task of running the family businesses.“

Although Isaac proved to be quite good at managing the family bank, his heart was elsewhere.: Music and art were his great loves. He was an avid art collector and aspired to devote himself to these pursuits, at a safe distance from money and banking.

As Isaac became engrossed in art and avoided getting married, the pressure for an heir fell on Moise. The eligible 31-year-old bachelor secured a good match in 20-year-old Irène Cahen d’Anvers, from one of the city’s leading families. Assouline tells us that, although the match was respectable, it wasn’t a marriage based on love - at least not on Irène’s part.

A year into the marriage, a son and heir was born – Nissim (named after his grandfather). Two years later the couple also had a daughter, Béatrice. Moise became part of Parisian high society, joining several Parisian social clubs.

Irène, on the other hand, refused to play society wife and sought out other interests. A decade passed and Irène asked for a divorce, after which she married her stable-master lover. She wed in a church, converted to Christianity and was no longer part of the family.

Act III: It all rests on Nissim

After his wife left, Moise sank into a deep depression. He understood that he’d have no further heirs and was destined to spend the remainder of his life alone in his house. He eventually realized that he had to start over. In addition to now taking care of his children, he developed an interest in art and design.

In April 1911, following the death of his beloved 60-year-old uncle, Isaac retreated further into his interest in art. He bequeathed much of his art collection to the Louvre, while further art pieces made their way to Moise’s own house. At the time, Moise was the sole owner of the family’s bank and artworks.

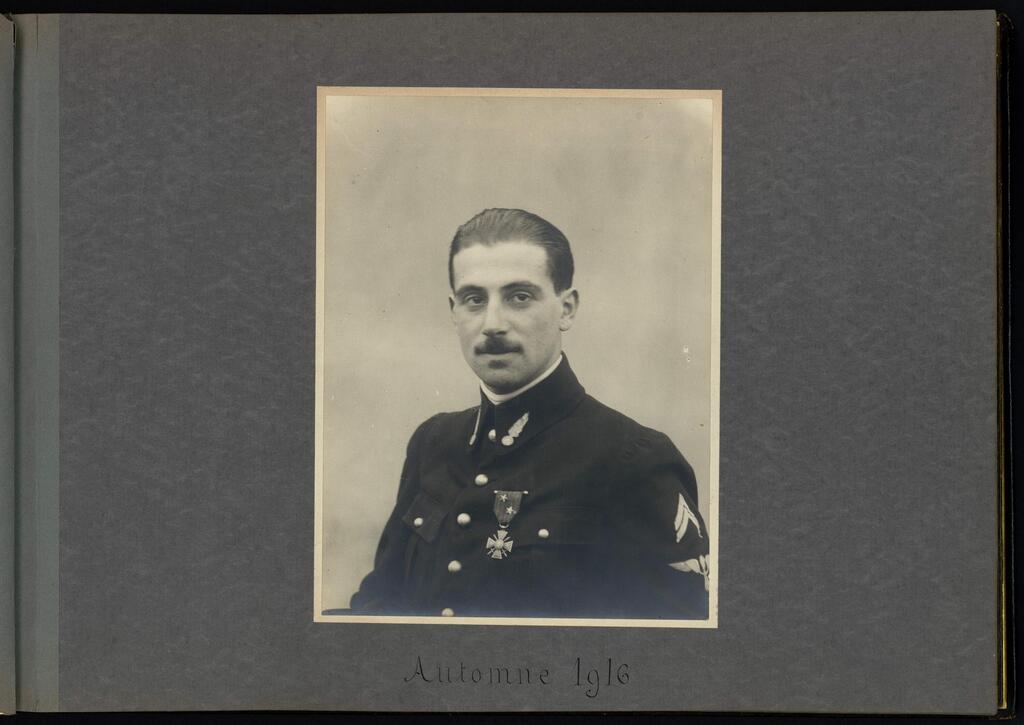

Moise knew that the burden of the family legacy would fall onto the shoulders of his only son, Nissim. By 1914, as war drew near, it was clear that Nissim would be drafted. The decree to save France came on August 1st. Along with a further 5000 French Jews, Nissim was recruited into the French Army. Assouline writes that “French Jews had to prove that in addition to loving France, they were willing to die for her.”

Nissim served as a pilot in the French Air Force. Although a proud father, Moise was filled with apprehension. Nissim was his only son and the war was raging. Months went by and Nissim carried on reporting from the front line, occasionally coming home on leave for family visits.

Moise’s anxiety did not abate. In 1917, the terrible news Moise was dreading finally arrived: The plane in which Nissim was conducting a photographic operation was shot down. Moise’s heart was shattered. For months, he held onto the hope that somehow, Nissim had survived. When he was eventually forced to deal with the reality of his son’s death, he dedicated his energies returning son’s body for burial in France.

Act IV: The inheritance becomes a memorial

Following the war and his son’s death, Moise retired from business. With no heir, he saw no point in continuing. He gave his lawyers and clerks power of attorney and devoted his time to his art collection.

He still had a daughter, Béatrice. She married Léon Reinach from a wealthy Frankfurt family. Béatrice was a keen equestrian and, to her father’s delight, had two children - Bertrand and Fanny.

Moise wrote a will in 1924. He left his house to France, on condition that it be turned into a museum and that nothing would be changed and that it would perpetually serve as a memorial to his son and his family: “No piece of furniture shall be moved from its place. Everything must remain as it is on the day of my death. It is forbidden to add or remove any item.” Assouline explains that in doing this, Moise guaranteed the memory of his name and that of his family.“

Moise died in his house - the place he loved best - on November 14, 1935, with his Béatrice by his side. “The last Camondo failed to continue the dynasty, but in creating his house and attributing to this house a unique soul, and persuading the country to register it in France’s artistic heritage, he managed to immortalize the names of his whole family. “

The Final Act: Like all the Jews

After Moise’s death, Béatrice and her children were the last survivors. Although they didn’t carry the Camondo name, they were Moise’s direct descendants. With the Nazi invasion of Paris, a fresh threat now hovered over them. As one of the richest and most respected families in the city, Leon and Béatrice foresaw no immediate danger.

The erosion of Jewish rights, confiscation of property and artwork took their toll. Reports from Eastern Europe about concentration and extermination camps were rife. In his book, Assouline writes that “Despite the dangers, Béatrice didn’t think to leave Paris. She carried on riding her horse every day along the forest trails in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne. She even took part in competitions with Nazi German officers.“

One day, early in 1942, the family were arrested and taken to the Drancy internment camp where they spent several months. On 20th November, they were put on a number 62 train to Auschwitz where they were gassed on arrival.

Various testimonies have tried to describe what happened to each member of the family and under what circumstances they met their deaths. Either way, none of them made it back from there. Assouline writes that “while Nissim died for France in the First World War, his sister and her children died at the hand of France that collaborated with the Nazis. Moise did not live to see this act of betrayal. “

This is how the story of a 160-year-old family comes to an end. The family left its mark everywhere it went, but reached the end of its journey with no descendants to carry on the family name.

Did the family receive the respect it deserved?

Assouline: “The family no doubt belonged to a milieu of 19th and early 20th-century Jewish aristocracy or upper middle class. They were respected and admired not only within the community, but by other powerful families like the Rothschilds, Cahen d’Anvers, Königswarters, Leoninos and many more. “

How did you come to research the history of this unique family?

“The quality and rarity of the art collection at the house on rue de Monceau that they bequeathed to France ignited my curiosity. It constitutes a gesture of enormous artistic, financial and symbolic importance. It was Moise’s way of paying his ‘entrance fee’ into French high society. I feel this unique inheritance, along with the story of the family’s wonderings and power is a story that needs to be told.”