Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The recent arrest of two teenagers, aged 18 and 19, in Austria, who pledged allegiance to Islamic State (IS) and planned a terror attack at a Taylor Swift concert in Vienna, has highlighted a growing threat: the recruitment of young people into Islamist and far-right terrorist organizations via social media, particularly TikTok.

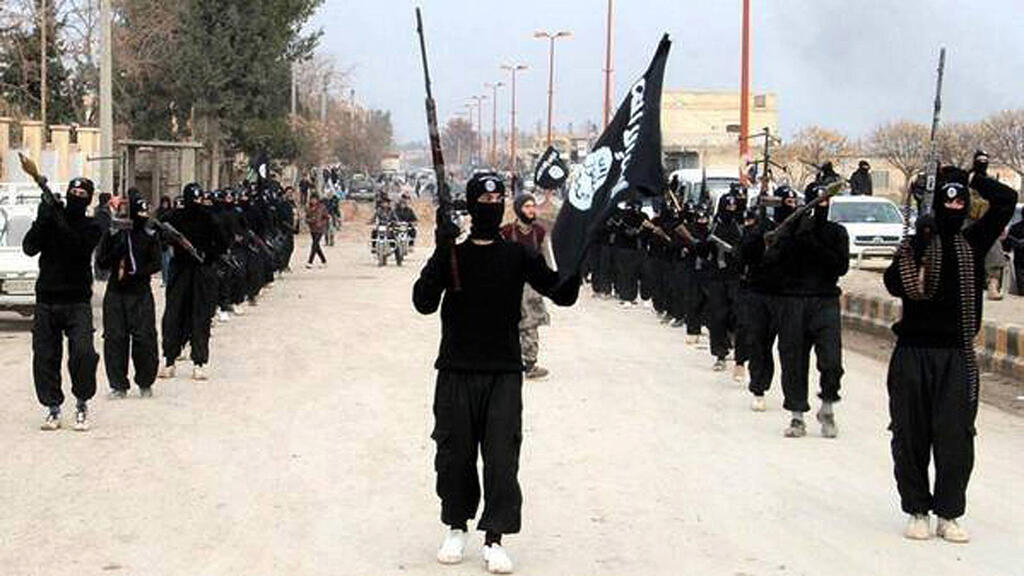

This phenomenon, dubbed "TikTok Jihad," has fueled a resurgence of jihadist activities targeting Europe. In the past ten months, the continent has witnessed six terrorist attacks, mostly small but some deadly, with over 20 planned attacks foiled by security and intelligence services.

In many cases, the attackers or would-be-attackers were youths radicalized online, including the two Austrian detainees and a third 15-year-old accomplice who was detained for questioning and released.

Intelligence experts note that TikTok is the preferred platform for recruiting young "lone wolves" or virtual terrorist cells due to its vast reach and algorithm. Meanwhile, Telegram is used to plan attacks and connect operatives.

This new recruitment method presents challenges for law enforcement in two ways. Monitoring, searching and identifying virtual meeting places is much harder for intelligence services than tracking in-person meetings between recruiters and recruits.

Additionally, the new channels require law enforcement and security agencies to work harder to profile "dangerous" individuals or those likely to join terror cells, as this involves gathering intelligence on young people not previously considered at risk. It's also a challenge for judicial authorities, who must decide how to prosecute minors in such cases.

In the past, the Internet served as a forest of Islamist propaganda for Muslims in Europe, who needed extremist imams or mosques to bridge the gap between them and terror groups. That bridge has disappeared. Personal meetings are no longer necessary, and the new generation needs only a virtual network to progress from radicalization to joining and acting.

Worse still, in the past, suspects were mainly from Muslim backgrounds or children of Muslim immigrants, but recent months have shown that radicalization has reached German or French teenagers with no ties to Islam or immigrant backgrounds. This is in addition to youth born in Europe but raised in parallel Muslim societies, disconnected from where they were born and raised, primarily consuming information from extremists online or Al Jazeera.

In March, a 15-year-old attacked a 50-year-old Orthodox Jew in Zurich, Switzerland, shouting "Death to Jews." After the attack, a video emerged of the Swiss boy, originally from Tunisia, pledging allegiance to IS and vowing jihad against Jews and attacks on synagogues.

In Germany, a terrorist cell was uncovered in April, leading to the arrest of two girls aged 15 and 16 and a 15-year-old boy from Düsseldorf. Wiretaps of their private chat group revealed plans to act for the “Islamic nation” by attacking churches and police stations to kill as many people as possible. The investigation found they were radicalized online, collected Molotov cocktails and stabbing tools and planned to buy firearms to stage an attack on Cologne's famous cathedral.

In May, a 14-year-old girl from Montenegro was arrested in Austria after buying a knife and ax in Graz, intending to commit a terror attack. Her computer contained Islamic State propaganda and incitement materials. Several French youths were also detained by security forces for planning attacks during the Paris Olympics.

Part of the shift to virtual recruitment is tied to the territorial defeat and dismantling of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in 2019. The idea lives on in the virtual cloud, prompting recruiters to scour social media for users interested in their cause.

Western intelligence experts warn that recruitment is now harder to detect because recruits are not ideologically aligned with the terror group but fall victim to the cynical exploitation by adults seeking bored teenagers, particularly those marginalized in society and disillusioned with life, growing up in broken homes.

IS recruitment is not portrayed as violent enlistment for a political-religious cause but as a platform for venting frustrations with parents, teachers and society. It offers an outlet for their mundane lives and a chance at dubious "15 minutes of fame." The recruitment of youths accelerated due to propaganda efforts by IS affiliates in Afghanistan and Central Asia, whose aggressive campaigns have revived the Islamic State's prominence in discourse and intelligence reports.

The October 7 massacre and the ensuing Gaza war have also fueled activity on social media. Network algorithms, particularly on TikTok, have facilitated the dissemination of relevant war-related content, radicalization and recruitment of youth. Since October, terrorist activities and attempts have quadrupled compared to the same period last year.

"Allah will make breathing difficult for you if you consume Western culture," warns a Muslim preacher named Abdul Hamid in a video caught by intelligence agencies in Düsseldorf. The clip, viewed 60,000 times, is in German and features Salafist and Islamist propaganda.

The preachers are often not religious figures but online influencers who speak to Generation Z in their language. They are the first point of contact to lead listeners and viewers into the "Salafism bubble," where they are bombarded with propaganda and recruitment materials disguised as clips offering solutions to everyday problems, laced with constant religious messaging and clear rules, promising to guide the youth out of confusion and provide moral compasses.

These portals also foster identity and empathy with young people, portraying themselves as outsiders in society and culture, similar to Muslim believers. Islam becomes a platform for counterculture. For many youths, Islamic activists become father figures, someone they can trust.

The plans of the Austrian youths (with immigrant roots) arrested for plotting the attack at the Taylor Swift concert are chilling: alongside IS propaganda booklets, they gathered machetes, firecrackers, axes, knives and hammers. The 19-year-old got a job at a metal factory to procure chemicals, while the 17-year-old secured work at the stadium where they planned the attack. They even acquired a police siren to place on their car to reach the venue and carry out a massive suicide attack. Their encrypted text exchanges with their handlers were in coded language, avoiding keywords that could alert security services.

According to a report by terrorism expert Peter Neumann, 38 of 58 people arrested for IS-related activities since October were aged 13 to 19. Recruiters continue their efforts, needing to enlist only one out of thousands of virtual candidates. They know no one would suspect a 15-year-old boy or girl of committing such heinous acts. The attack on the Taylor Swift concert may have been thwarted, but the threat remains.

Franz Ruff, director general for public security in Vienna, explained that those arrested in the foiled Taylor Swift concert attack were radicalized online. He noted that communication among the plotters used codes to mislead surveillance agencies. "It's as if they were having conversations," he told journalists in Vienna.

The German newspaper Bild reported that the main suspect in the Taylor Swift concert plot was influenced by a well-known Islamist preacher online, Abdul Barah, who shifted to online preaching after his Berlin mosque had been closed, gaining tens of thousands of followers.