Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem, also known as Sholem ben Menachem Nachum Rabinovich, wrote extensively about Hanukkah in his stories. But if you think these tales are brimming with warm scenes of candle lighting and donut feasting – prepare to be surprised. For Sholem Aleichem, Hanukkah serves as yet another opportunity for satire, allowing him to peel back the layers of the funny yet tragic lives of his characters: the Jews of the small shtetls in Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

In Sholem Aleichem's Hanukkah stories, you might occasionally encounter warm latkes or Hanukkah gelt, but the real focus lies on the Jews portrayed in them. These five stories – “Tlafim [Hooves],” “What is Hanukkah?,” “Hanukkah Latkes,” the children’s tale “Hanukkah Gelt,” and the short play “The Wheel Turns Backwards” – depict the Jews of the small shtetls as greedy, cunning and ignorant, more interested in finding kosher (and not-so-kosher) ways to make money than in observing the holiday's commandments. Yet Sholem Aleichem doesn’t judge them; instead, he laughs along with them.

'Tlafim': On heretics and forbidden foods during Hanukkah

What do Jews do on Hanukkah? Play cards, of course!

Sholem Aleichem recounts the holiday customs in the shtetl: "In the past… we played cards only once a year – on Hanukkah." That is, he clarifies, cards were played on other days throughout the year too, but secretly. On Hanukkah, however, a group of young men would gather openly for this "custom" at the home of one of their own, a man who was already smoking on Shabbat and eating "non-kosher sausage." His home was a paradise of transgressions: There, one could read a newspaper or a "forbidden book" (not a holy text), "smoke a cigarette on Shabbat, eat treif sausage on a fast day – and especially play cards," or as they called them, Tlafim (a play on the Hebrew word Klafim – cards, but using the word for a pig’s hooves).

The group sat in the house, engrossed in a game called "Oka," until two unmistakably dressed men arrived – silk garments, beards and long sidecurls. They introduced themselves as the grandson of the Baal Shem Tov and his gabbai. They had come seeking a donation, but upon witnessing the scene in the room, they asked to stay a while and observe the game. They claimed they had never seen playing cards before. Mesmerized by the game, they exclaimed: "We’ve grasped the idea! This is the Evil Inclination!... Do us a kindness, let us join in!... We want to experience the taste of Tlafim too!"

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The two devout men join the game and nearly lose all their money. But as the game stretches into the early hours of the morning, their luck turns, and they end up bankrupting all the other players. Was it a miracle from heaven? Morning prayers are about to begin, but the group insists that the two bearded men stay and play a little longer – perhaps they’ll lose back what they’ve won. They even urge them to try some food. However, the moment the devout pair discovers the nature of the dried sausage being served, they flee for their lives. The group delights in the “trick” they’ve played on the two pious men, but it soon becomes clear that the devout men had their own tricks up their sleeves. In this story, Hanukkah begins to resemble the costume-filled antics of Purim.

'What Is Hanukkah?': No one in the shtetl actually understands the holiday

At the start of the story, Sholem Aleichem finds an invitation on his desk: “On the occasion of Hanukkah, we humbly invite you for a cup of tsivim” (tsivim – tea). The narrator immediately understands the true meaning of this “cup of tea” – a card game, of course. The host is a wealthy, assimilated Jew, and his home boasts a large hall where around 50 Jewish men and women sit at tables, playing cards. A friend of Sholem Aleichem wagers with him that not a single Jew in the room will be able to explain, in a few words, what Hanukkah is about. The two proceed to go table by table, asking the participants.

The story serves as a snapshot of bourgeois, assimilated Judaism at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Sholem Aleichem paints vivid portraits of the colorful characters he encounters: young men with pockmarked faces, men with shiny bald heads or grand bellies, some with yellowish hair and others graying, all far more devoted to their games than to any interest in Judaism.

The hostess responds to them: "Hanukkah is a kind of holiday that... that’s called Hanukkah." One of the players explains: "Hanukkah is a holiday where you can play Preference" (a card game), while another adds: "And eat latkes cooked in fat." Someone else remarks: "Hanukkah? We’re not Zionists." Another explains confidently: "On Hanukkah, you should know, it’s a mitzvah to play cards." When they reach the women’s tables, one of the ladies asks the guest, "Why are you just standing around? Why aren’t you playing?"

After going from table to table, they finally come across a nine- or 10-year-old boy who is learning Hebrew and agrees to answer them. "Hanukkah? Hanukkah? Of course!... My father... my mother... my father eats... what’s it called?... matzah with mishloach manot... and my mother spins a white chicken like this... and we eat Jewish dumplings." Naturally, Sholem Aleichem loses his bet and has to pay his friend 25 rubles.

Even in today’s Israeli society, not all Jews are well-versed in Jewish holidays, but if Sholem Aleichem were to make the same bet today, he wouldn’t lose. Most Jews in Israel are well acquainted with Hanukkah and its story. Well, we have an excuse: We’re Zionists.

'Hanukkah Latkes' (1903)

In this short story, centered around Hanukkah latkes, the focus is not on holiday traditions but on the colorful Jews of the shtetl – particularly the glaring inequality between the poor and the wealthy. The town's aristocrats invite all the townspeople to their large courtyard to taste latkes on the first night of Hanukkah. The event starkly highlights the class divide: on one side, the wealthy, seated at tables in the courtyard, adorned in their finest clothes and jewelry; on the other, a crowd of beggars forced to sing and dance in honor of the holiday as a condition to fill their stomachs with the luscious latkes.

Sholem Aleichem vividly describes the "crowd of beggars" gathered in the courtyard, their eyes fixed on the latkes – a mixture of goose fat (schmaltz), flour and yeast, portrayed here as a delicacy: "Mainly destitute, beggars, paupers, the impoverished... they pounce eagerly on the Hanukkah latkes, devouring them ravenously, dipping the warm, soul-reviving latkes into the fresh, fragrant schmaltz. The aroma permeates every fiber of their being, and the taste – it’s the taste of paradise."

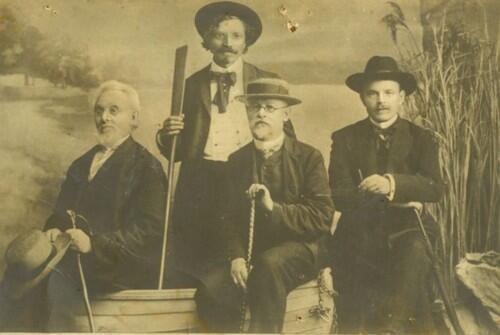

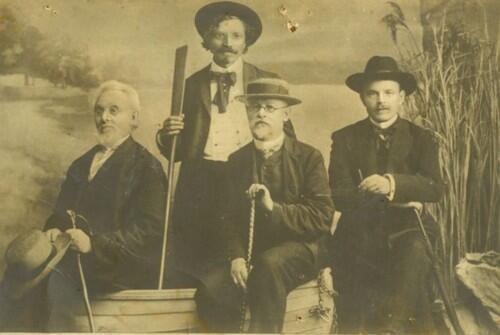

3 View gallery

Great Jewish and Hebrew literary figures in Odessa, Ukraine. From right: Chaim Nachman Bialik, M. Ben-Ami, Sholem Aleichem and Mendali Moche

(אוסף גלויות היודאיקה ע"ש יוסף ומרגיט הופמן, הספרייה הלאומית)

It seems class divides have always been with us, but if Sholem Aleichem were writing this story today, he would likely compare store-bought donuts to gourmet “chaser” donuts filled with patisserie cream and a touch of ricotta.

'Hanukkah Gelt'

This is a children's story about two brothers visiting their relatives from house to house, trying to collect Hanukkah gelt. But, as always with Sholem Aleichem, the focus isn’t on the holiday traditions but on the pathetic, humorous and colorful characters of the children's relatives, who try every which way, with an array of excuses, to avoid giving the children any gelt. "What do children like you need money for?" one uncle asks, "And how much does your father give you?" Even after reluctantly placing a few old – and likely worthless – coins in their hands, he mutters to himself about parents spoiling their children by allowing them to ask for Hanukkah gelt.

But alongside the sharp critique of the Jews in the shtetl, Sholem Aleichem also captures a few of the holiday traditions: children play with dreidels and "bones" (likely a type of checkers) using black and white groats, and they eat warm pancakes (latkes), which he describes as "warm, smeared with fat, with steam rising upward." Yet even here, he doesn't forgo humor. Alongside the mouthwatering descriptions of the latkes, he portrays the cook who prepared them, wiping her filthy hands on her dirty apron and then rubbing those same hands on her nose, leaving a conspicuous mark on her face.

As in many of his stories, children serve to heighten the absurdity of the situations and to voice truths, however harsh they may be. We can’t help but wonder what Sholem Aleichem would have written about the children of the TikTok generation.

Play: "'The Wheel Turns Backward': A cinematic play for Hanukkah

This Hanukkah story is unique because, for once, a candle-lighting ceremony is described. Yet even here, Sholem Aleichem's primary focus is not on the ritual itself but on the processes shaping Eastern European Jewry across generations. He depicts the lighting of a menorah over three generations.

In the first generation, the ceremony is highly festive: many guests gather in a home to light a large silver menorah, which is supported atop the shoulders of two lions and winged eagles. Servants bring out large bowls filled with latkes, a variety of delicacies, and fine wines. The guests give Hanukkah gelt to a little boy, Itzikl, who plays with a dreidel inscribed with the letters Nun, Gimel, Hey and Shin: Nes Gadol Haya Sham (A great miracle happened there). Incidentally, as in previous stories, the guests also play card games and Ishkuka (chess).

In the next generation, Itzikl is now grown – he's a father himself – and it is his elderly father who lights the menorah. The lighting is done discreetly, solely in honor of the old man, and it’s evident that if he were no longer alive, the menorah wouldn’t be lit at all.

In the final scene, Itzikl's son has grown up, and once again, the ancient holiday menorah hangs in its usual place. This time, it is not the elderly grandfather – who has passed away – lighting it, but his grandson, a Zionist university student, a fact that fills his mother with shame. "She burns with humiliation. She never imagined, never could have conceived, that from her home disaster would emerge, that her own son, her flesh and blood, would stray into... into this culture!" She almost apologizes to her guests, saying, "The wheel turns backward..." The Zionist grandson defies his assimilated parents and revives the forgotten tradition of the holiday. Today, this might be called religious coercion.

We would be delighted to inform Sholem Aleichem that his prediction was spot on: the Zionist grandchildren of his characters indeed light menorahs with great pride in almost every home across the Land of Israel.

From a Jewish shtetl to a Jewish state

More than a hundred years have passed, yet Sholem Aleichem's sharp satire remains remarkably relevant in Israel of 2024. Even today, we grapple with tensions between secular, traditional, and religious communities; with insufficient knowledge about our traditions; with class disparities; and with the ongoing clash between tradition and progress. However, if you think we’re in the same situation, you’re mistaken. We’ve transitioned from the Jewish shtetl to the Jewish state, and with that, our responsibility to find solutions to these challenges has grown significantly.

This article is courtesy of Mashav Channel – What's Jewish in Israel, a platform for Hebrew content related to shared Jewish identity in Israeli society, operated by the Tzohar Rabbinical Organization.