Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The final draft of the maritime border deal between Israel, Lebanon - brokered by the United States - highlights one important point. The U.S. is more than just a negotiator in this agreement, it is a party to the deal and a guarantor committed to solve any future disputes between Israel and Lebanon surrounding the maritime border and economic waters.

This has strategic value for Israel, because Washington is committed to Israel's security and the wellbeing of its citizens and does not appear to have a similar commitment toward Lebanon. In order to balance the field, the final draft does say the U.S. is committed to offer immediate assistance to Lebanon by supplying it with needed oil. This important provision was not known until now.

Beirut and Jerusalem will both inform the UN of the agreement soon, but it will not become binding until the U.S. announces it has been given an approval from both, Jerusalem and Beirut.

The success of the deal brings the U.S. back as an active player in the Middle East, with sway over Lebanon, which has always been under the French influence.

Washington will also benefit from the almost immediate sale of natural gas to Europe, extracted from the Karish gas rig, replenishing some of the lost supply to the continent caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

This may offset some of the criticism against U.S. President Joe Biden, who seems to have been ignored by Saudi Arabia despite his efforts to ensure an increase in energy production.

In the wording of letters, which Beirut and Jerusalem are to submit to the UN, it will be described as having a territorial dimension, under article 16(2) of the UN charter. According to Opposition leader Benjamin Netanyahu, this means there is an element of territorial concession on the part of Israel.

But the territory in question is not land, but some six square kilometers (2.31 square miles) only, at the tip of Israel's territorial waters that had not been officially recognized until now, because of the maritime border dispute.

It was a complicated matter because according to the agreement, the international northern boundary of Israel's economic waters began at the western edge of the line five kilometers away from shore. It will now break to the south, in order to include the predominate portion (83%) of the Qana gas field in the Lebanese economic waters.

The agreement stipulates that this will have no relevance to the land border between Israel and Lebanon and that the beginning of Israel's territorial waters will be determined in the future, only after the two countries agree on their complete boundary.

3 View gallery

Lebanon Prime Minister Najib Mikati, presents final agreement to President Michel Aoun

Lebanon now agrees that the maritime border - marked unilaterally by Israel – five kilometers (three miles) from the shoreline, is acceptable.

Since Lebanon is an enemy of Israel, the fact that there is an internationally binding agreement between the two countries, has political relevance to Israel's standing in the Middle East.

As to the economic aspect, the agreement states that production from the Qana gas field will yield revenue to Israel. That is guaranteed by the U.S. in the final draft of the agreement, which stipulates that drilling will be carried out by a "reputable international firm, not under sanctions," or in other words a western company under legal jurisdiction of where it is registered.

Gas from Qana is expected to be extracted by the French Total company and perhaps a second firm, so if Israel does not receive compensation as specified in the agreement, it would be able to appeal to a court in France or Italy.

That would not have been possible if Lebanon would have gotten its wish to have a Russian or Iranian firm do the drilling.

The agreement does not stipulate the percentage of revenue Israel will be due, and it will be finalized after further negotiations with the drilling companies without Lebanese intervention - despite their earlier demands to be included in the final decision.

This is a good agreement that balances Israel's security interests as well as its political and economic ones.

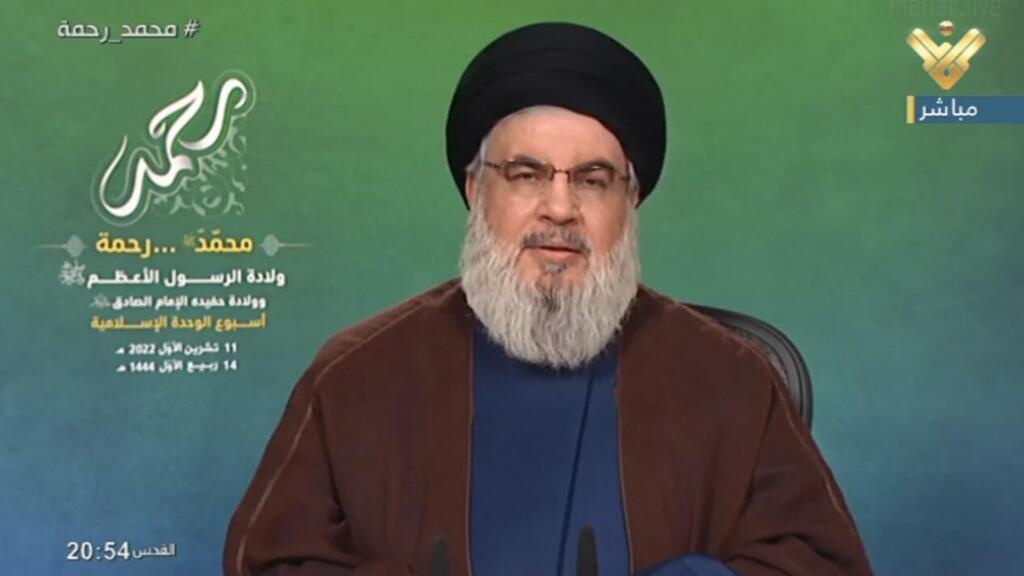

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, meanwhile, also capitulated to pressure and green-lit the deal even though his masters in Tehran opposed any such agreement - , according to Israeli intelligence sources.

Nasrallah had to give his consent after pressure from the government in Beirut, seeking to end the economic crisis that has plagued the country in the past few years, which was caused partly by the actions of the Iran-backed group.

He realized a deal would be reached with or without his approval, and could not oppose it. He decided therefore, to make threats so that when Israel and Lebanon reach an agreement, he could claim his threats were effective. He has no doubt mastered the skill of making lemonade out of lemons.

Israel's leaders, Prime Minister Yair Lapid and Defense Minister Benny Gantz, on the other hand erred when they rushed to celebrate the deal before it was sealed. This was in the service of their election campaigns.

U.S. mediator Amos Hochstein was able to prevent the new Lebanese demands from making it into the deal, saving it, which is not only good for Israel, but also constitutes a gift to Biden, one he may choose to repay in kind to Lapid.