Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In the early 19th century, Christian missionaries arrived in northeastern India, bordering Myanmar, and encountered people who firmly held on to their monotheistic traditions amid a completely polytheistic environment. These were the tribes of Chin, Kuki and Mizo, later identified as "Bnei Menashe."

More stories:

Over time, some of the Bnei Menashe made Aliyah and settled in various places across Israel. Many reside in settlements in the Benjamin region, such as Beit El, or near Gaza (where many relocated after the 2005 disengagement from Gush Katif). The members of this unique group have integrated into Israeli society, but their distinctive traditions and tribal stories are gradually fading from the historical memory of the younger generation.

Rabbi David Lhungdim, who immigrated to Israel in 2007 and now resides in Sderot, is making every effort to combat this. He writes books, collects information and connects the ancient tribal traditions to the Sages' words about the descendants of the Tribe of Menashe.

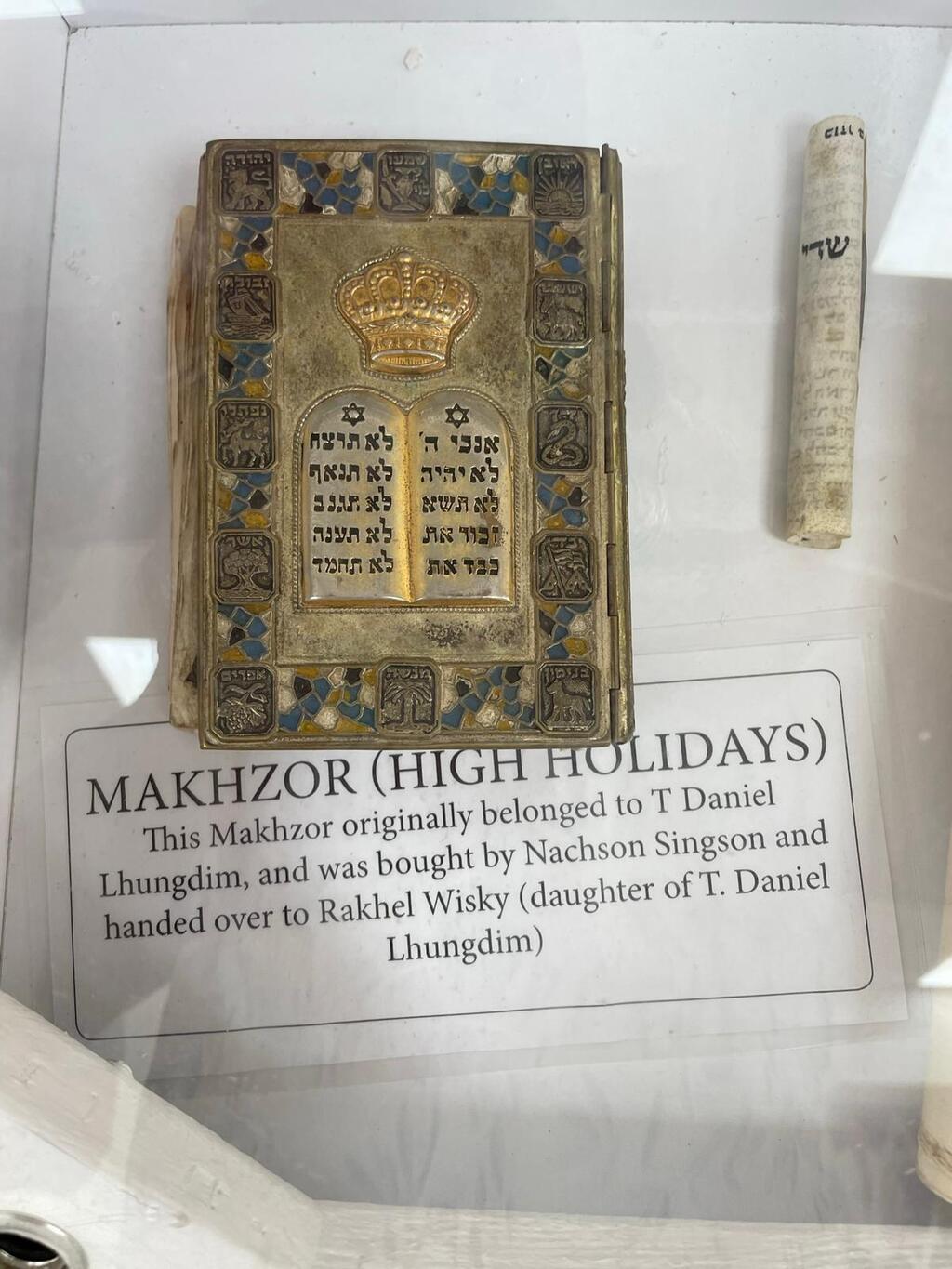

Recently, he has been working on establishing a new museum containing artworks, letters and various artifacts related to the Bnei Menashe, planning various activities for the youth. However, apart from the municipality of Netivot, which supports their cause, there is currently no government entity that actively supports the group and preserves its unique cultural heritage.

Sabbath or Sunday rest?

According to Rabbi Lhungdim, large groups of the Bnei Menashe in India embraced Christianity following the arrival of European missionaries. "They identified the possibility that it was a tribe excluded from the Children of Israel and redoubled their efforts to convert the population."

The process of conversion was swift, and by 1920, the entire tribe had already become Christian. However, the old traditions were not forgotten quickly. In the 1960s, a man named Daniel Lhungdim (no family relation) realized that the elders' ancient tradition, passed down from generation to generation, a hidden and more primitive tradition, did not align with the Christian beliefs he was taught.

"He was educated with degrees, a rarity in our community in those years," says the rabbi. "He was the first to start examining the tribe's customs and make connections between them and what he found in the 'Old Testament' - the Tanakh received from the missionaries."

"For example, our elders used to say that whoever works on the seventh day would not receive blessings in their work," he elaborates, "and then Daniel Lhungdim began to question himself: How could it be that the elders speak about the seventh day as a day of rest from labor, while in Christianity, they are required to rest on Sunday?"

Crying out to the heavens during an earthquake

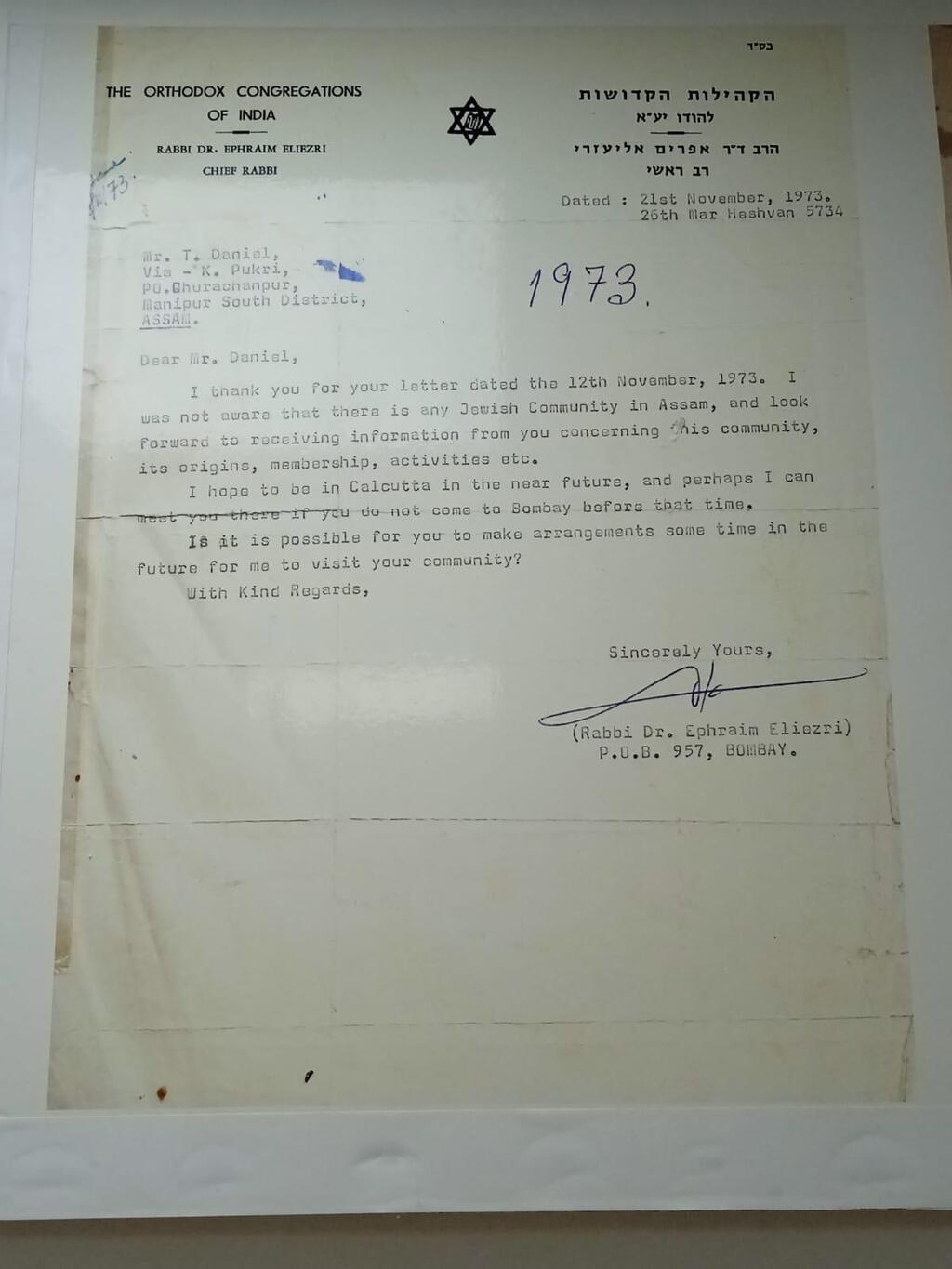

Daniel Lhungdim did not remain indifferent to these revelations and traveled to Mumbai to meet the Bnei Yisrael community there and learn more about Judaism from the community’s Rabbi Ephraim Eliezri. "He started visiting libraries in Mumbai and collecting materials," says the rabbi. "At the end of his research, he came to the conclusion that we are the tribe of Menashe."

One of the main things that led him to this conclusion was an ancient custom of the elders of the tribe to come out during earthquakes and cry out to the heavens: “We are your children, the children of Manssiah Chai (Menasseh is alive), we are here." "All this while not knowing the meaning of ‘Manssiah Chai’," the rabbi says.

"They believed that the Holy One, blessed be He, would come to search for them and take them to their land, so they cried out to Him that they were here. I still remember seeing this sight when I was 22. They kept this tradition even after converting."

Daniel Lhungdim’s revelations from the beginning of the previous century were what drove the process of recognizing the tribe in Israel. According to the rabbi, the continuous persecutions that the tribe suffered for centuries forced them to move from place to place to survive and made it impossible for them to observe the commandment of circumcision. However, another tradition was preserved: on the eighth day, the tribe would poke a small hole in the infant’s ears. "Children born uncircumcised were immediately proclaimed as reincarnations of the ancient forefathers, who were circumcised," he notes.

The Bnei Menashe had unique customs surrounding Jewish holidays. For example, before Passover, they would slaughter a white rooster and eat it without breaking any bones, similar to the Pesach offering. "They ate a special bread made from rice, as there was no wheat there, but for Passover, they prepared unleavened bread without any leavening agents, which was a special bread for the holiday."

Yearning for the promised land

Not only do the pre-Christian customs around burial, the seven days of mourning and levirate marriage, reflect a monotheistic tradition, but also ancient customs related to their tragedy. "For example, when someone passes away, a family member would take a sword and start reciting their genealogy orally. They would recite a text starting with the words 'Manssiah is with him' and continue through the generations until they get to the deceased. All this was part of the oral traditions passed down," says the rabbi.

“The deceased would be buried with their head facing east, symbolizing the direction of the Land of Israel. They would cry out, saying that the stones, sand and trees would make way because today, 'the son of Menashe' is returning to his land. In our language, a more accurate translation would be 'the good and fertile land’."

Three names mentioned in the tribe's genealogy book could hint at specific members of Menashe settling beyond the Jordan: Menamashi, Gilead and Ulam. "These are Hebrew words from the Tanakh. The first is Menashe, the second could be Gilad, the grandson of Menashe, and Ulam - other descendants of Menashe living in the land of Jabesh-Gilead across the Jordan," explains Rabbi Lhungdim.

According to the aggadic-midrashic work Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, written over a thousand years ago, it is mentioned that the tribe of Menashe received a special promise as a result of their deeds. When the Philistines desecrated the body of King Saul and left him hanged in the elements, 400 "valiant men" went and buried him and his son on the land of Jabesh-Gilead. The promise they received was that in the future, the return of Jews from exile would begin with them.

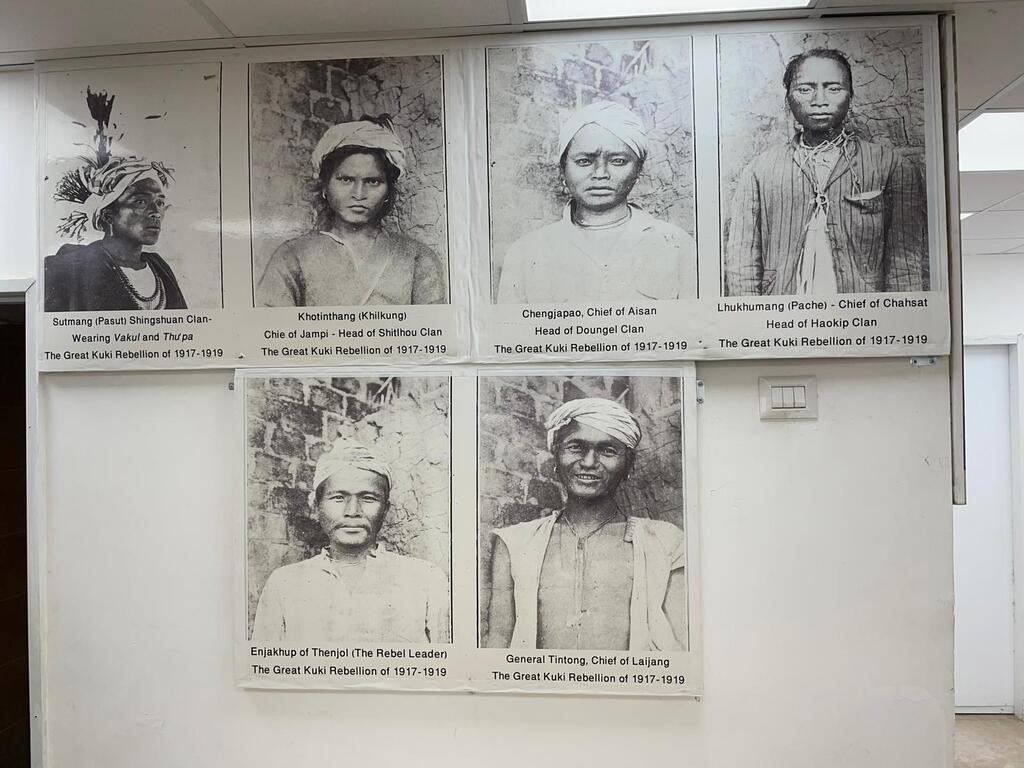

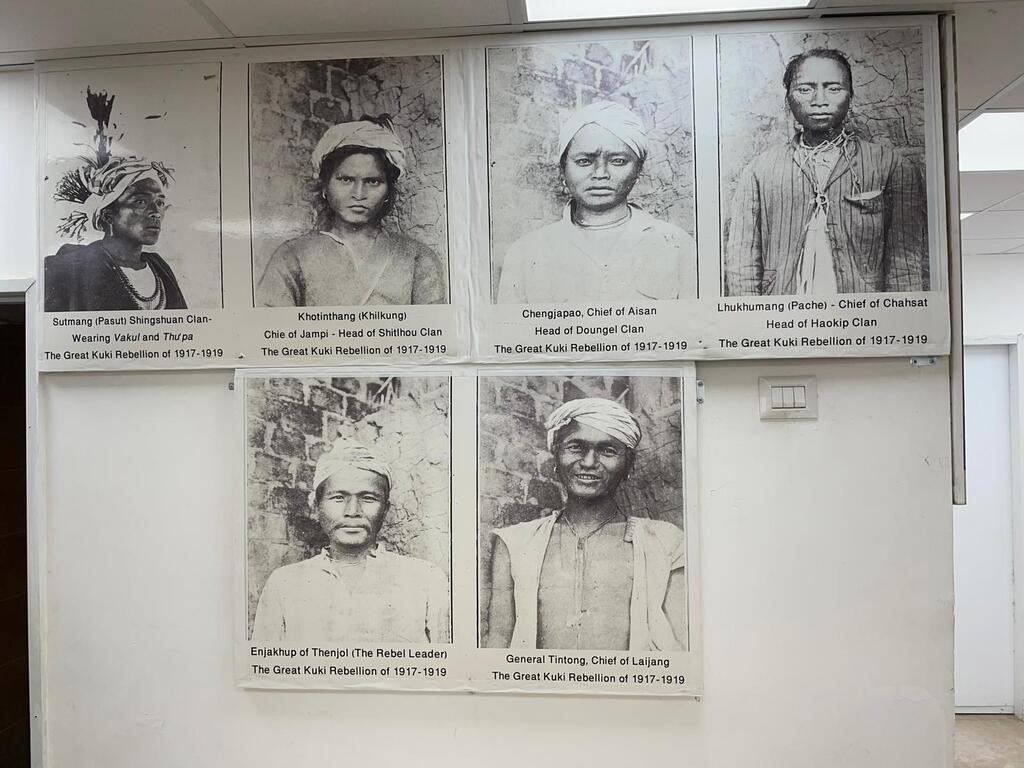

8 View gallery

Photos of the Bnei Menashe tribe in traditional attire from the exhibition at the museum

Preserving the heritage

Rabbi Lhungdim, 39, was born on the India-Myanmar border. Even before his immigration to Israel, he began to compile the ancient traditions into a book written in English titled "Menash – Manmashi: the Lost Tribe of Israel."

"I realized that it is important and will bring benefit," he says. "I used sources that included Chazal’s works (the early Jewish sages). I sent copies of the book to the National Library. Unfortunately, since I am also working on other projects simultaneously, I don't have time to translate it into Hebrew. I hope to find someone who can help us fund this project."

In Israel, he studied under the late Rabbi Aryeh Gamliel at the Yeshiva of Sderot, and later, during his stay in Migdal HaEmek for the purpose of assisting fresh Bnei Menashe Olim, he studied at the yeshiva headed by Israel Prize laureate Rabbi Yitzchak Dovid Grossman.

"Somebody asked me for the pictures, the ancient artifacts and the writings that we have in the small museum we opened. I did not agree to that," he reveals. "We need to preserve our heritage and artifacts in our own hands and not give them to an external entity, God forbid. It should be preserved for future generations."

Jews by ancestry but required to convert

The letters that Rabbi Lhungdim refers to are correspondences exchanged with Rabbi Eliezri and the Israeli consul in Mumbai, sharing their discoveries. Rabbi Eliezri couldn't make it to North-East India to meet the tribe, but Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail took his place. He made finding the lost and scattered communities, including descendants of the ten tribes, his life mission.

Rabbi Lhungdim recalls meeting Rabbi Avichail as a child. "At first, he couldn't enter the areas where the tribe lived, so he met with them outside the region. In 1988-1989, he succeeded in reaching one place and was welcomed by the community members. During his subsequent visit in 1994, I was a schoolchild. I remember seeing him and thinking he was an angel. I had a desire to follow in his footsteps."

Ultimately, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel addressed the question of the Jewish identity of the tribe and then-chief rabbi Shlomo Amar eventually acknowledged that the tribe had Jewish roots. However, he argued that in order to reintegrate them into the fold of Judaism, they would need to undergo conversion. The Chief Rabbinate actively pursued their conversion.

Praying in a caravan

According to Rabbi Lhungdim, the ancient songs of the tribe not only preserve historical events from the history of Israel, such as the splitting of the Red Sea, but also keep in memory the stages that the tribe passed through to this day, which, according to him, also included Afghanistan and Tibet. In the memory of the tribe, there is also a tale of a "holy book" that accompanied them on all their journeys, and according to their accounts, it was taken and burned by the ling of China – since then, the tradition of the tribe has been maintained through oral songs and traditions passed down from generation to generation.

Many communities in Israel have heritage museums that preserve their unique customs and traditions, but Lhungdim and the Bnei Menashe receive no external support. "Currently, no one supports us except for Sderot Mayor Alon Davidi who provided us with the place to operate the museum," the rabbi explains.

"The municipality assists through its integration department, but it's not enough. We really want to organize activities for our youth, establish some community center and a synagogue. Today we pray in a caravan, which is not advisable in a city like Sderot, which is significantly exposed to rocket fire from Gaza."

"I primarily want this place for the younger generation, so they will know who they are, why they came here, and what their ancestors went through so that they can return to our people," he adds. "If we don't ensure that they know and remember, everything will be forgotten – because they won't receive this information from anywhere else."

Moreover, he seeks to strengthen the public's familiarity with the Bnei Menashe and the unique tradition they have preserved throughout their years in exile.