Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

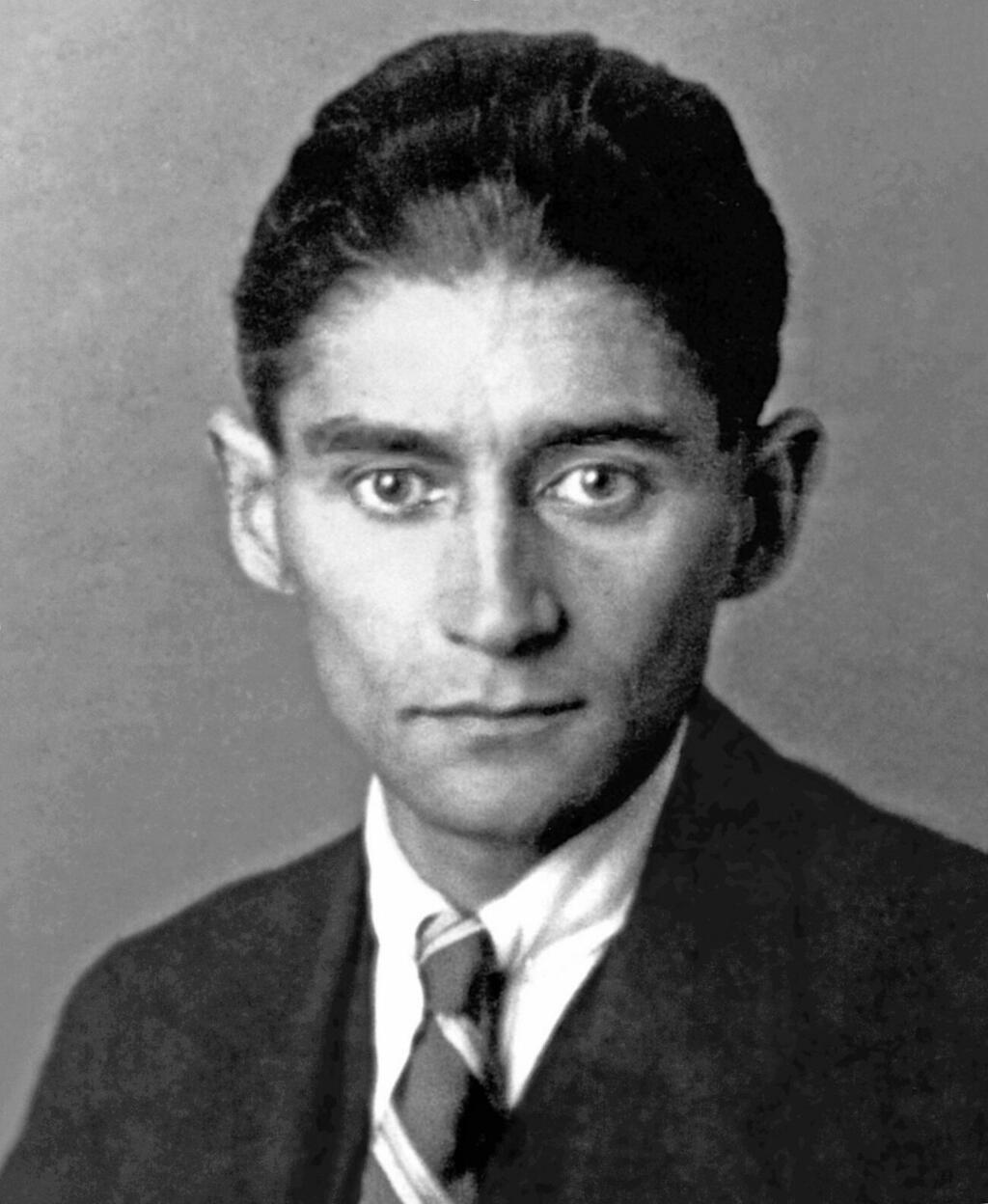

The Jewish writer, Franz Kafka, was one of the greatest contributors to Western culture in the 20th century, influencing many writers who came after him and passed away at the young age of 40 (this June will mark 100 years since his passing). Despite leaving instructions in his will to burn all his works, his good friend Max Brod chose to ignore his wishes.

Over the years, we learned new things about Kafka such as his vegetarianism, his tendency to sleep with open windows, and even his habit of nude sunbathing in remote forest streams. A less-known fact about Kafka is that two of the greatest Hasidic rabbis of his time influenced his life. One of them had a tremendous, decisive influence on his love life.

Kafka's connection to Judaism and perhaps also to Zionism, alongside the influence of the rabbis on him, was discussed in an episode of Israel's National Library's podcast, "HaSafranim," hosted by Vered Lyon Yerushalmi, the library's spokesperson, and Dr. Stefan Litt, a humanities scholar and archivist of German collections in the library.

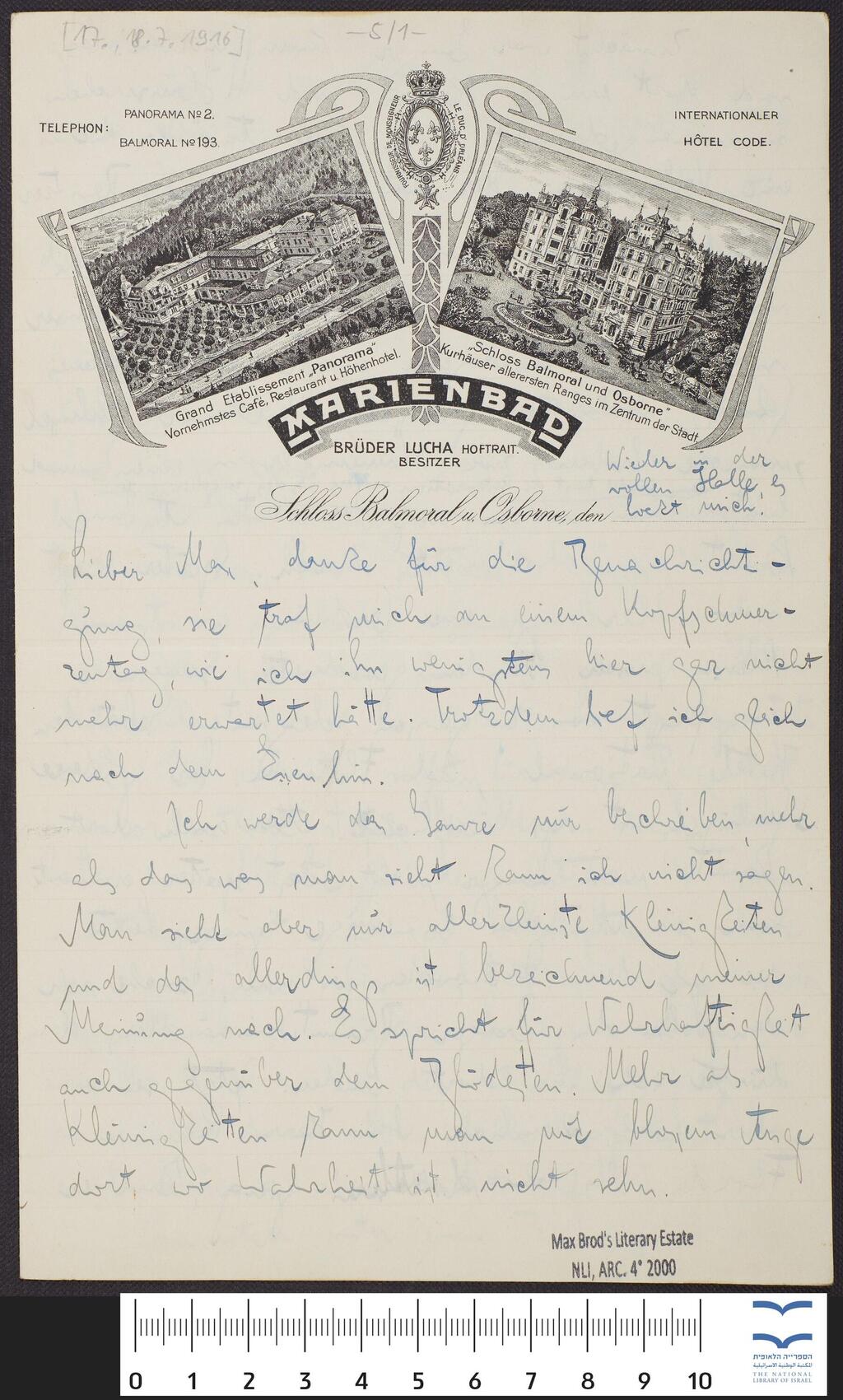

In 1916, Kafka was invited to accompany the revered Rebbe from Belz, Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach, on a tour. At the time, Kafka came down with tuberculosis and stayed at the Bohemian baths. He then happily accepted an invitation from a good friend, philosopher, Jiri Mordechai Langer to join the tour. He wrote about his impressions of the Rebbe in a letter that has now been translated into Hebrew for the first time.

"He looked like the Sultan I saw in my childhood in Gustav Doré's illustrations for Baron Munchausen's stories. But it wasn't a costume; he was truly the Sultan. And not only the Sultan, but also a father, a teacher in elementary school, a professor in high school, and so on," Kafka wrote to his friend Max Brod.

"His appearance, his hand placed on his waist, his broad back as he turned – all these inspire confidence. Everyone's eyes looked at him with undisturbed confidence and tranquility, which I also felt. His height is average and his body is very broad, but he moves with ease. A long, white beard, particularly long sideburns... One eye is blind and sunken. His mouth is curved, giving him an ironic and amiable look at the same time," he adds.

Kafka continues to describe the Rebbe's appearance and the electrifying influence he has on his people, all less impressive than their leader. Some argue that his description is relevant, at least in part, to the ultra-Orthodox street of the 21st century.

"In the entourage, a special role is given to four members, who comprise the "inner circle". The senior member of the four, according to Langer, is a one-of-a-kind villain; his big belly, his smugness, and his slanted gaze seem to indicate that. By the way, this is no reason to blame him, all of the Rebbes' entourages are deteriorating. You can't be close to the Rebbe without adverse effects, a normal mind can't tolerate it."

"Kafka did not plan for this letter to be published one day, certainly not translated into Hebrew," says Dr. Litt, "he merely described what he saw, but we received a unique anthropological experience: the Rebbe as a mediator between the community and God, which leads to blind admiration on one hand and perhaps an exploitation of the status by the 'inner circle' on the other." Yerushalmi points out that Kafka was on one hand captivated by the Rebbe, but at the same time, wished to emphasize that power corrupts man.

Spiritual Zionism

Kafka's parents, Hermann and Julie, were not religious, but their parents were. "During the 19th century, it was quite scandalous if your grandparents weren't religious," says Dr. Litt, "Kafka didn't grow up in a religious household, but he was influenced by tradition to some extent, which was evident in his life."

Perhaps that's why when the Yiddish theater arrived in Prague in 1911, the 28-year-old Kafka was drawn into the new and unfamiliar world. He met an actor named Yitzhak Levi, who became his soulmate. During those years, he discovered Zionism, although not fully committed to its values. He attended the Zionist Congress in 1913 and even dreamt of moving to the Land of Israel, but remained in Europe for the time being.

"His closest friends were passionate Zionists, such as Hugo Bergman and, of course, Max Brod, and this fact undoubtedly led to numerous internal conflicts. On the other hand, it should be remembered that Stefan Zweig's close friends were Herzl, Buber, and Weizmann, and he wasn't exactly like them," says Litt. Like many educated German Jews, Kafka believed in spiritual Zionism. "He believed in the need for spiritual and internal preparation for Zionism, alongside the establishment of a cultural and spiritual center in the distant land, which might prevent assimilation which threatened the Jewish people," said Yerushalmi.

Jewish Script

Kafka diligently studied the Hebrew language. One of his teachers was a young Jewish woman from the Land of Israel whose mother tongue was Hebrew. Some argue that he fancied the teacher, which probably contributed to his motivation. In the National Library's archives, one can find the legendary's writer notebooks containing Hebrew lessons with minor spelling mistakes, humor, and chapters from the Bible. His fellow Hebrew scholars were astonished when Kafka showed decent proficiency in the ancient language.

Is it possible to identify Jewish motifs in his writing?

"Max Brod, who published Kafka's first biography, leaves no room for doubt that Jewish motifs can be identified in his writing," say Litt and Yerushalmi, "but in general, there are no explicit Jewish references."

How do you identify Jewish motifs?

"An important Israeli artist once told me that the most beautiful thing about Kafka is that there are no exclamation marks at the end of his sentences. You don't really understand him until the end," Litt says, "There is something very Jewish about it, not to believe the written word but to investigate its significance. Crowds of people who read Kafka and wrote about him are convinced in their hearts that only they discovered the true meaning of his writing."

Love till Death

Kafka's life ended sooner than expected. He fell deeply in love with a Jewish girl named Dora Diamant. They met in Waren, where Dora volunteered at a summer camp for refugee children. The love that blossomed between them led them to decide to move to the Land of Israel and open a restaurant in Tel Aviv where Kafka, planned to be the waiter. He proposed marriage to his beloved, but Dora still asked for her father's approval, who was from Ger Hasidic community. Kafka wrote to her father: "Although I am not an Ultra-Orthodox, I am ba'al teshuvah."

The 'end of days' feeling that hovered over him projected the Jewish, not necessarily the Zionist, desire to reach the Land of Israel, to die there and be buried there

The father turned to his rabbi, and Rebber Avraham Mordechai Alter replied no. "Perhaps the most universal figure in Western culture, who writes about absurd and fantastic issues, did not receive the approval of the Rebbe to marry his beloved in an Orthodox wedding," said Yerushalmi. Although there are no records, it's possible that he did not want to encourage marriages between a Hasidic girl and a non-observant writer. The two did not marry, but their love did not wane until Kafka's death, and Dora, who remained alone, lived a turbulent and agonizing life until her early death.

Kafka himself was not religious in his later years, but it is evident that he gravitated towards his Jewish identity. "When a person reaches the finish line and is aware of it, he strives to get closer to the things that give him comfort, and the 'end of days' feeling that hovered over him projected the Jewish, not necessarily the Zionist, desire to reach the Land of Israel, to die there and be buried there," concluded Dr. Litt.