Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

When serial spouse King Henry VIII wanted holy support for his divorce from first wife Catherine of Aragon over the lack of an heir, he found no quarter from Italy's Rabbi Jacob Rafael of Modena.

The English king, searching for biblical grounds on which his marriage might be annulled, in 1521 canvassed the opinion of religious scholars.

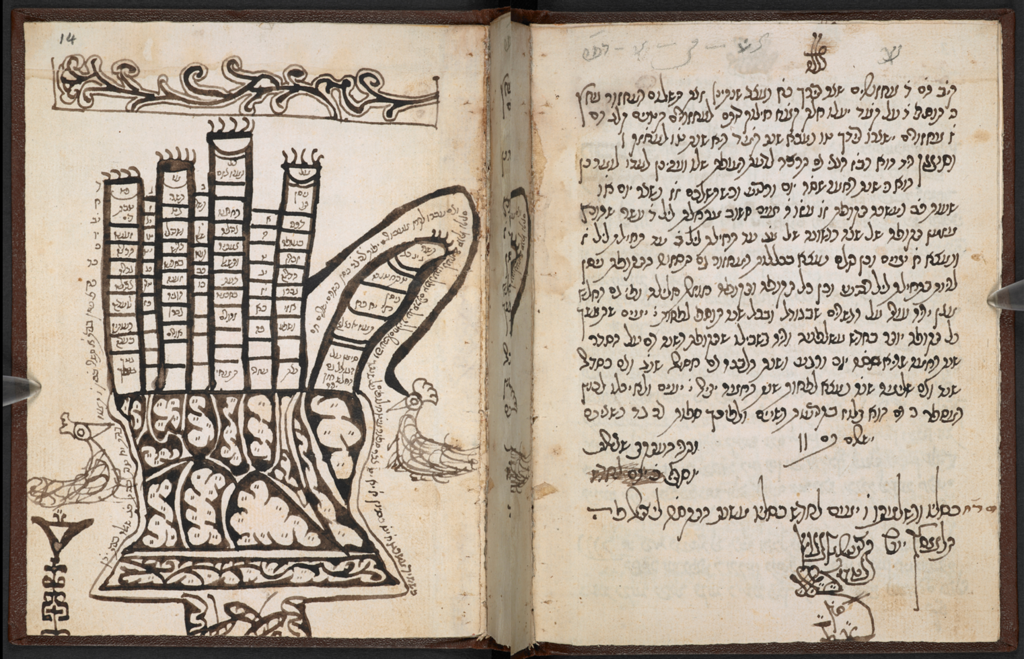

6 View gallery

King Henry VIII, left, and the letter from Italian Rabbi Jacob Raphael

(Photo: British Library Board)

The king initially set out to prove that the Pope's dispensation for him to marry his brother’s widow Catherine was invalid.

After Henry failed to convince Rome and expanded his search for biblical grounds on which his marriage might be annulled, it is believed that the bishop of London in 1529 suggested that he seek the advice of Italian rabbinical authorities.

Thus began a process to consult and obtain support from the Jews of Venice.

Jacob Raphael, the rabbi of Modena, did not supply Henry with the opinion he was seeking, agreeing with the Church that based its ruling on Leviticus, the third book of the Old Testament.

In a letter written in Hebrew and Italian, Raphael articulated his argument that explored the question of Levirate marriage, when the brother of a man who died without children is permitted and even encouraged to marry the widow.

The king nevertheless had his marriage to Catherine annulled in 1533 by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Parliament the year after declared the king to be the supreme head of the Church of England, beginning the Reformation and the break from the Roman Catholic Church.

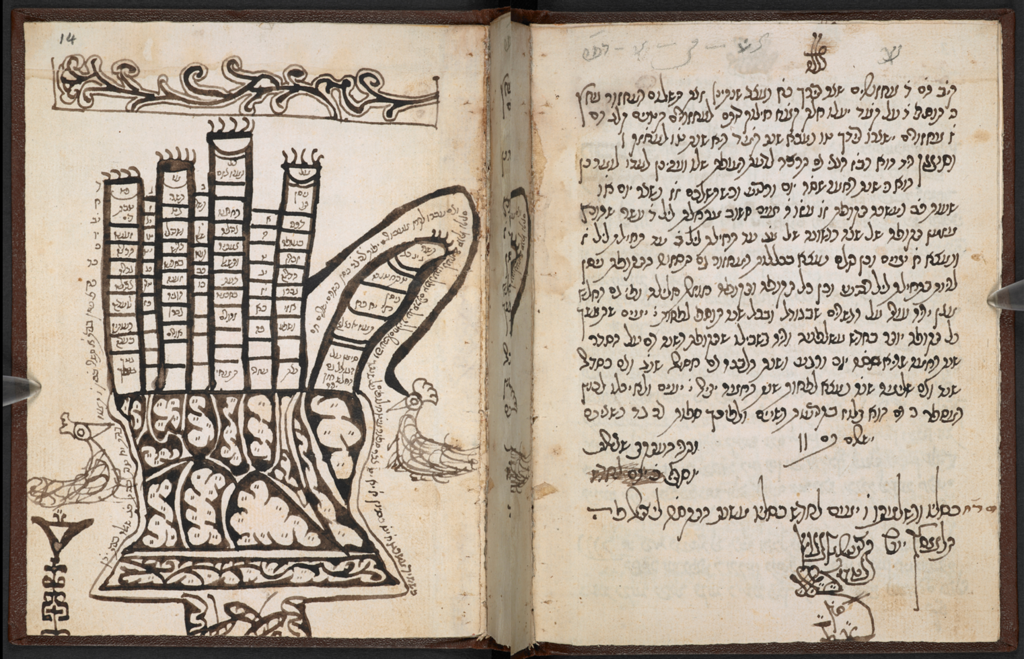

6 View gallery

The Hebrew Manuscripts exhibition at the British Library in London

(Photo: British Library Board )

The letter is part of an exhibition at the British Library that will remain open to the public until June 6, 2021.

It is titled Hebrew Manuscripts: Journeys of the Written Word and includes 40 of the approximately 3,000 documents in the British Library and is available online.

Spanning science, religion, law, music, philosophy, magic, alchemy and Kabbalah, highlights include one of the first Jewish scientific works written in the Hebrew language; a manuscript containing instructions for mystical meditation; a spell book containing 120 magical and medical recipes; and one of the few extant copies of the Babylonian Talmud, the British Library said.

"We wanted to show things that were never seen before by the public," exhibit curator Ilana Tahan said.

6 View gallery

Ilana Tahan, curator of the exhibition of Hebrew Manuscripts exhibit at the British Library

(Photo: British Library Board)

"Written culture is one of the most important bonds connecting Jewish communities all around the world. Jewish writings reflect the diasporic communities of the Jewish people, taking inspiration from and interacting with local cultures and shaping local stories and ideas in return," said Tahan, who has been with the British Library for 31 years.

The earliest exhibit is the First Gaster Bible, the earliest object in the exhibition dating from the 10th century, which is considered one of the most important biblical codices to survive. It originated in Egypt and shows the influence of Islamic art in its illustrations.

Among other texts are a Catalan bible from the 14th century and Torah scroll that belonged to a Jewish community in Kaifeng, China from the 17th century.

6 View gallery

A 700-year-old Hebrew bible exhibited at the British Library

(Photo: British Library Board)

A 13th century document depicts a Medieval Jewish woman owning property and engaging in business dealings in England. The document shows deeds of the sale of a house in Norwich in the east of England after Miriam, the wife of one Rabbi Osha’ya, gave up her rights to the property before it could be sold.

The Jewish community in Norwich was first mentioned in 1144, during one of Europe's first notorious blood libel events in which English Jews were accused of the ritual murder of a young boy.

The deeds included in the exhibition are just a part of a small collection of manuscripts that have great historic importance, according to Tahan.

“What fascinated me about these documents — some of them are in Latin with a little bit of Hebrew but there are some that were written entirely in Hebrew — is that it appears that these kind of documents were accepted in England at that period,” says Tahan, adding that beyond their historic authenticity, they show Jews held high positions in business at the time.

Tahan also notes that the inclusion in the document of the Hebrew words "We bear witness," indicates that there was an active Jewish community using the language in contracts that were acceptable not only in the Jewish world.

While documents in Hebrew were found, they only predated the expulsion of Jews from England on the order of King Edward I in 1290 by a decade. Ironically, 250 years later another English monarch reached out to a Jewish rabbi to help him with his marital woes.

Tahan says medieval Christian courts destroyed many of the Hebrew manuscripts, which they considered blasphemous. Others survived however, and some - including a rare 13th century Talmud that is part of the exhibit - found their way to the British Library.

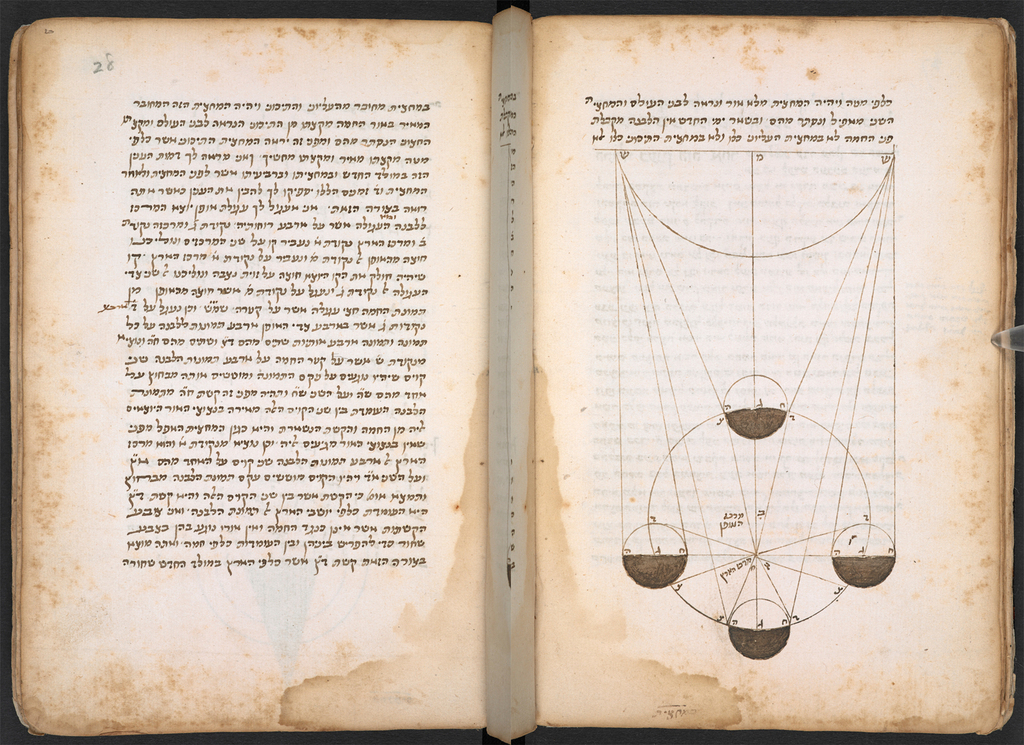

6 View gallery

A 15th century depiction of the Earth by a Jewish mathematician

(Photo: British Library Board)

Other such finds include a 17th century edition of the Sefer Hazikkuk (lit. the book of refinery) by Domenico Gerosolimitano, which lists 450 Hebrew texts considered to be theologically dangerous by the Catholic Church and therefore destroyed for their blasphemy.

Gerosolimitano was born Jewish but converted to Christianity. He censored over 20,000 Hebrew books and texts including a 700-year-old version of the Jewish religious law written by German Jewish scholars.

But censorship was far from the worst fate, Tahan says, which included the torture of Jews.

"You can see it in several of the manuscripts," she says.

An example shown in the exhibition is of a copy of Rabbi Ishmael Hanina’s account of the interrogation and torture he suffered at the hands of the Papal Inquisition in Bologna in 1568.

“He was on trial as a representative of his religion and he had to defend the religion,” she said. The trial took place a few months before the Jews of Bologna were expelled.

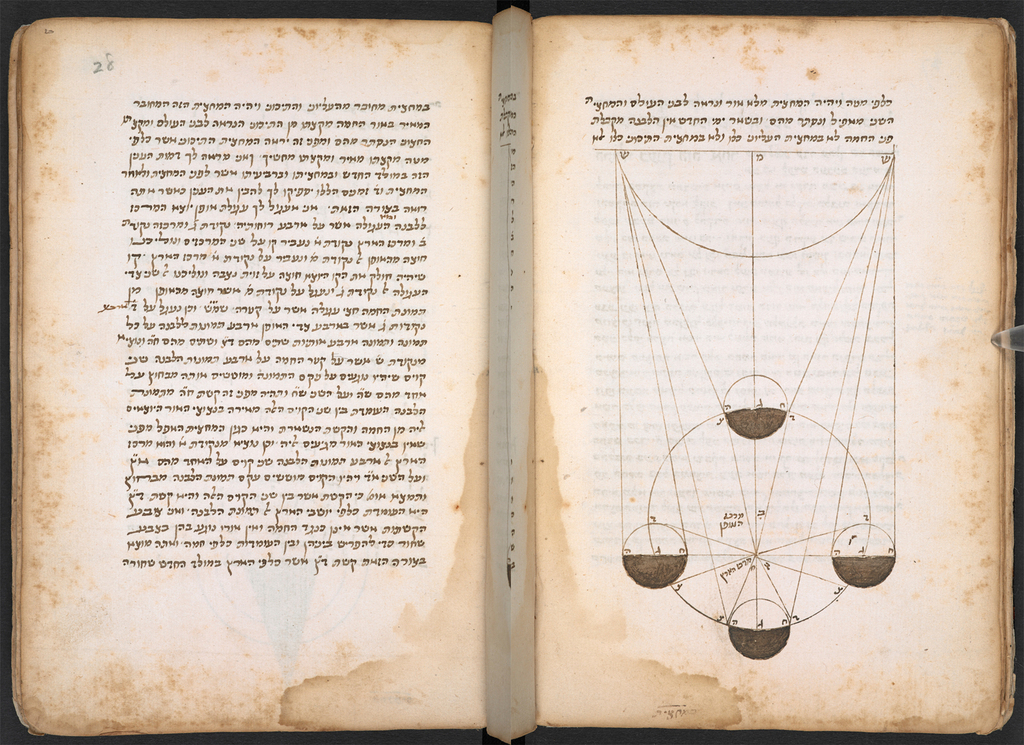

One of the most impressive items Tahan included in the exhibition is a 1380 copy of the “Guide for the Perplexed” by revered Medieval Jewish physician and scholar Rabbi Moses Maimonides (also known as the Rambam) that was in the possession of the Jewish community in Yemen and written and in a Judeo-Arabic dialect.

6 View gallery

A copy from 1380 of Rabbi Moses Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed

(Photo: British Library Board)

The 12th-century Jewish philosopher was born in Cordoba, Spain and was one of the most influential Talmudic scholars of the Middle Ages.

The book is a brightly colored 14th-century copy of a translation into Hebrew; its images of a lion, scholars believe, may suggest it was commissioned for the Spanish royal court.

The British Library exhibit is open until June 6, 2021.