Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

I was a young rabbi in a religious kibbutz where we had a seminary for conversions to Judaism.

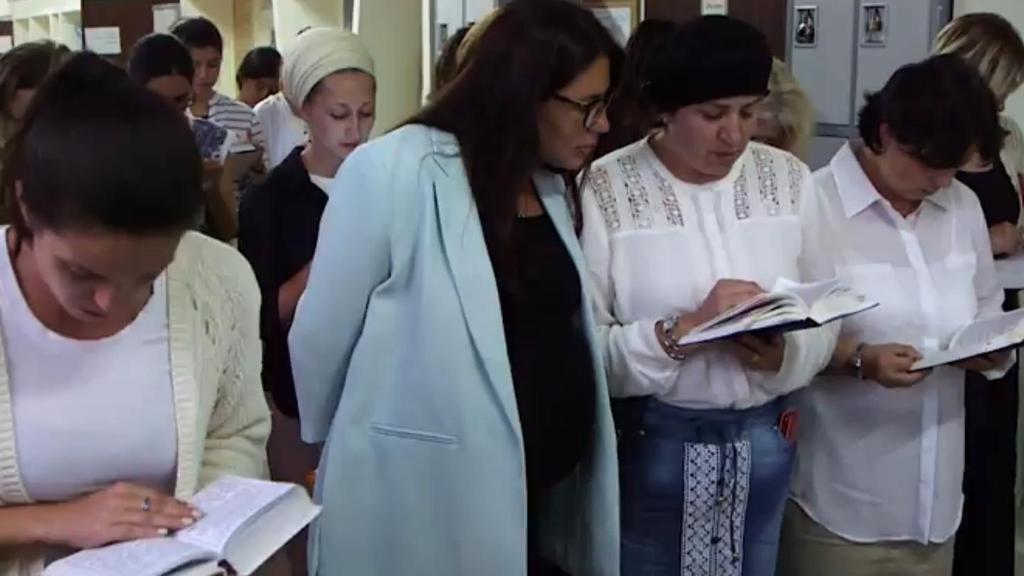

Dozens of young families and single people came each year to begin their new lives as Jews.

One Friday night, as the conversion course was nearing its end, my extended family and I sat with the conversion students around a long table in the communal dining room.

I was not raised in an observant home. We were traditional, but in my youth, I and my sister were not versed in Jewish law (Halacha) or the commandments of the faith.

At some point during the evening, one of the soon-to-be-converted students asked me to test the group on their studies. They were preparing for their final exams and their nervous excitement was evident.

I fired some questions at them about dietary laws, Shabbat and charitable contributions. My sister, who was raised in the Israeli educational system and was an officer in the military, seemed stunned. She did not know the answer to any of the questions.

I have been fortunate to know many people who had converted to Judaism; I conducted their children's marriages and I knew their grandkids well.

I had met many soldiers serving in the IDF who had taken upon themselves the complicated and daunting process of conversion, which strengthened their Jewish and national identity and their faith.

Did some give up mid-way through? Do some now lead a secular life devoid of religion? Sure, just like in any other community.

Conversion is hard. Almost inhumanly so. A person decides to sever their roots, shake up their life, uproot it and transport themselves to an unknown land. It almost always demands a person begin life anew, changing their relationships with the parents who brought them into the world.

Conversion is following in the footsteps of biblical patriarch Abraham. It demands whole-hearted adherence to God's words: "Go forth from your country, and from your kindred, and from your father's house, to the land that I will show you," (Genesis, 12:1)

We have been fortunate to return to our ancestral land, to make its desert bloom, to grow its economy, and see it transformed into a virtual superpower.

We must not turn away those who come to our gates wishing to convert to our faith. We must not treat them with suspicion, question their motives, or make their lives a misery.

The process of converting is a challenge that requires introspection. It places incredible demands on all who wish to join the Jewish people; we must not compound these challenges by adding humiliation to them.

Conversion must not be conducted through overly stringent positions that overshadow our welcome of new members of our faith.

We cannot place on them burdens that ignore human needs, dreams and desires. We cannot shut our ears and close our eyes to challenges posed by our world and our lives.

Conversion is a profound learning process that rewards all who take it upon themselves as the key to a new life.

Spiritual leaders, community, and city rabbis must present a moderate Halachic position that is not alienating. They must sound their respect for those who wish to convert in a clear voice.

In the words of Rabbi Hillel: "That which is despicable to you, do not do to your fellow, this is the whole Torah, and the rest is commentary, go and learn it."

Shai Piron is a rabbi, educator, and politician. He served as a member of the Knesset for Yesh Atid between 2013 and 2015, and as education minister between 2013 and 2014