Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The world will commemorate Victory in Europe Day (VE Day) on Monday, May 8, a day that honors veterans from Allied Forces of the United States, United Kingdom and former Soviet Union who fought against the Axis powers of Nazi Germany.

Other stories:

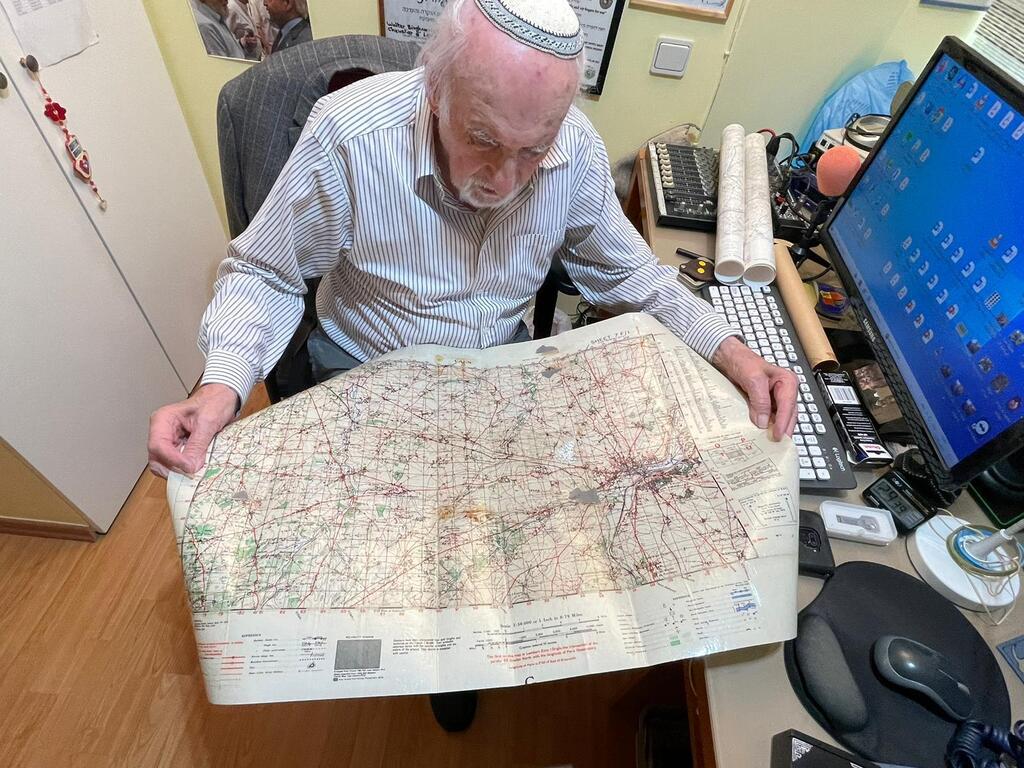

While there are many stories of bravery and heroism, one of the most unique is that of the Guinness World Records' oldest working journalist, Walter Bingham – a 99-year-old man who escaped the Holocaust, and is a decorated veteran of the British army and a proud Israeli Zionist.

But those descriptors only touch the surface of the fascinating life of Walter Bingham, who sat down with Ynet this week to discuss his journey to Israel and the historic events he was a part of in the 20th century.

Bingham was born in January 1924, to a religious Polish Jewish family living in Germany. He told Ynet that everything seemed fine while living under the Weimar Republic during the first three years that he attended school, but that rapidly changed as the Nazis came to power. Even as a schoolboy, Bingham experienced horrendous antisemitism.

“Things in school were not very nice … we sat two by two at a desk, and the other boy, a German boy, sat next to me, copied from me. ... He got good marks and I got bad marks. When I lifted my finger to try and answer one of the teacher's questions, I wasn't called on … I wasn't called anymore because the teachers couldn't take the chance that the Jew knew something a German didn’t.” This type of antisemitism carried on until the Jews were ultimately kicked out of schools in Germany.

The situation only escalated from there. Bingham personally witnessed the burning of books by the Nazis.

“We saw book burnings in early 1933. I saw that, where they threw German culture onto the fire,” he said.

But while many German Jews were not alarmed yet, Bingham and his parents were acutely aware of how grave the threat was early on.

In Germany at that time, there was a large population of Polish Jews in addition to the German Jews. While the German Jews were very integrated, the Polish Jews tended to be outcasts, even within the Jewish community, he said. “We lived there knowing what was happening, really understanding. But the German Jews … had a big shock,” according to Bingham.

Failed immigration to Israel

Growing up around the escalating antisemitism, Bingham said he was keenly aware of the importance of Zionism and the land of Israel, having been raised on Zionism “like mother’s milk.” In 1937, Bingham joined a Zionist movement which later became part of the Bnei Akiva youth movement and was supposed to immigrate to the Mandate for Palestine, but his request - like those of thousands of other European Jews - was rejected by the British, who administered the mandate. Bingham even went through agricultural training to prepare him to work on a kibbutz, but was unable to secure passage into the country.

“I knew what was happening. We knew that it wasn't good for Jews. At that time, of course, it was not the extermination policy – it was the policy of ‘get rid of them’ and nobody would take us. … We lived our life hoping for the best, but it got worse each time; then came the Nuremberg laws, which restricted life even more,” said Bingham.

So instead of immigrating to the land of Israel, Bingham at the age of 15 escaped from Germany, without his family, on the Kindertransport, along with hundreds of other Jewish children.

“I don't know why I was selected and not my cousins, but I was fortunate … on the 26th of July, 1939 – that's practically a month before World War II – I landed in England,” he said.

Bingham explained that he remains quite angry with Britain about its stipulations for the Kindertransport. That's because, while they somehow agreed to take in 1,000 Jewish children, their stipulation was the children be unaccompanied minors. This resulted in the separation of hundreds of Jewish children from their parents in an unimaginably challenging situation.

The Kindertransport

“Everybody knew that it was going to be war. When this transport came, the parents were heroes. They put their children on the train, staying and knowing full well that war would break out any moment," Bingham said. "I knew where I was going, but there were four-year-old little ones whose mothers put them on a train and the children were screaming ‘mommy, mommy, I love you.’ They thought they were being punished. … It was horrific. I want to tell you that 99.9 % of the Kindertransport children never, ever saw their parents again.”

While Bingham began a new life in England, his family remained trapped in Germany as Poland passed restrictive laws against Polish Jews who wished to return. Poland "issued the denationalization law, which stipulated that all Poles who had been out of Poland for five years or more needed to validate their citizenship to get the stamp in the passport. When all these Polish Jews went to the consulate, they were refused. No Jews. Jews didn't get the stamp. Now, overnight, all the Polish Jews were stateless,” he said.

Because of this, Bingham's father ultimately was sent to the Warsaw Ghetto, where he died of tuberculosis in 1941. Only a miracle – or fate – allowed Bingham to avoid deportation in the year before he got on the Kindertransport. Due to the expulsion of Jews from German schools, Bingham was sent to a Jewish school in another town, where he witnessed the events of Kristallnacht in November 1938, including the torching of a synagogue.

“I saw that the fire service was there, not to dash any flames but to protect the neighboring German property,” he said.

After seeing the horrors of the antisemitic campaign, he said, “I contacted home and said, I want to come home. My mother said, ‘Stay where you are. They just took your father… She told me that they said to her, You have a son, where is he?' I was in another town. And she said, ‘Oh, he's gone out somewhere. I don't know where he's gone.’ Otherwise, I'd have been with my father and not here today.” Bingham’s mother also was deported to a labor camp near Riga, Latvia, but survived the Holocaust and they were eventually reunited after the war.

A military life in the UK

Meanwhile, in the UK, the struggles were far from over for Bingham, despite the fact that he escaped from Nazi Germany. As a foreigner with Polish citizenship, he was drafted by the Polish military in exile in the UK, which was quite prominent there at the time.

“They called me up and I went there to the office and I said, ‘Listen, I'm not going into your army. First of all, I've never been to Poland. I know nothing about Poland. I can't speak Polish … and this is really true, you are antisemitic. I'm not going into your army.'”

Instead, Bingham joined the British military and served as an ambulance driver, including during the invasion at Normandy.

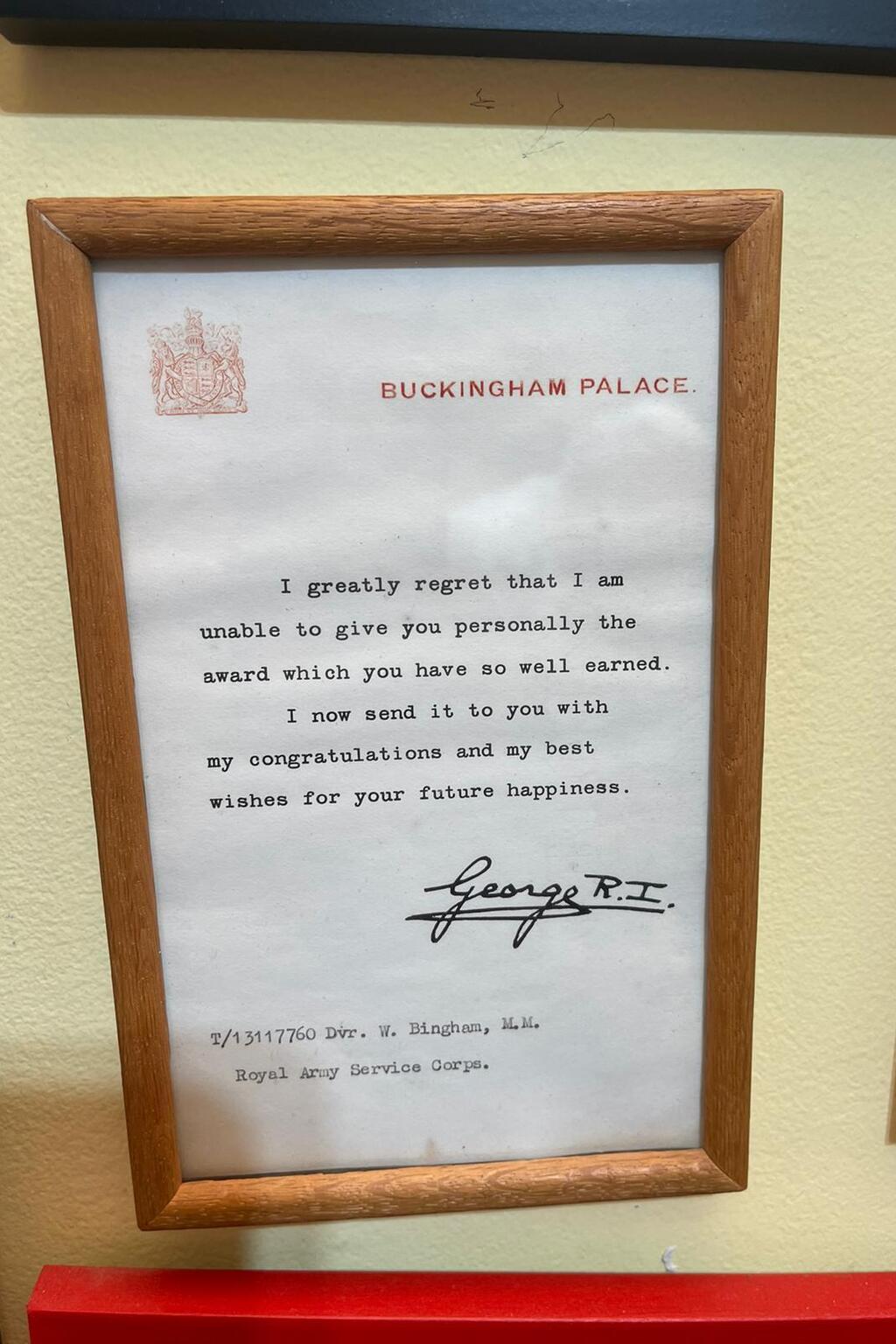

“I was trained [by the British] and then I landed in the water in Normandy during the invasion. …I was with the ambulance in the height of the battles so much so that I got a declaration for bravery from the team,” he said.

Intelligence service in Germany: To catch a Nazi

During his military service, Bingham ultimately was given a position in intelligence due to his language skills, which include fluent German, just before the battle over the Rhine River.

“There was a secret office on one corner of Oxford Circus [in London]. It was a big department store in the middle of the space. Under the roof was a secret office, and that's where I went. I was trained as a document specialist in content intelligence,” he said.

Shortly after the war, Bingham was sent to Hamburg, Germany to work in the British army to help to find Nazis, after the British intelligence took over the Nazi party headquarters. He said, sarcastically, that almost overnight “you couldn't find one Nazi. Nobody was a Nazi!”

In his role as an intelligence officer, Bingham reviewed German documents and helped identify Nazis. He recalled specifically one meeting that has stayed with him to this day, when the foreign minister of Nazi Germany, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was called into his office for questioning. Bingham questioned him about the Final Solution and Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews – all of which he denied.

“Today, we live in a period similar to the 1930s in Germany … and the only difference is that we have the State of Israel and it cannot come to a Final Solution”

“He was the man in charge of it all, he knew," according to Bingham. "He said to me, ‘I didn't know anything about the Final Solution, that was the Fuhrer.’ Well, you can imagine how I felt. He was sitting in front of me, one meter away from me in my office. I could have choked him. But … I couldn't do anything. Otherwise, I'd be in trouble. I could ask questions. I said, ‘I see, but you’ve now heard about it. How did you find out?’ And he said, ‘I read it in the newspaper'.”

Throughout the interrogation, Bingham said Von Ribbentrop exuded arrogance to an astounding level. At one point, when Bingham took out a camera to take a photo, Von Rippentrop asked if it was for an article for publicity and asked if he could shave first!

“You see, he thought he was a big shot … and he’s sitting opposite this 22-year-old soldier. He thought I was a silly boy,” Bingham said. But the joke was on Von Ribbentrop. Following multiple interrogations, Von Ribbentrop was one of the first to hang in the Nuremberg trials.

From soldier to journalism and aliyah

In the years following the war, Bingham continued to pursue a career in journalism, more specifically in radio – which he continues to do even today. He also began contributing to the Jewish News in the UK, as well as to the Jerusalem Post, where he has been a contributor for many years. In radio, he began at Israel National News radio with 10-minute segments from London, despite being significantly older than the average broadcaster.

5 View gallery

Guinness World Records certificate for the oldest journalist

(Courtesy Walter Bingham)

Bingham’s passion for journalism continued over the years until he ultimately decided to make Aliyah in 2004 at age 80, and continue contributing from his new home, Israel. “I came [to Israel] and Arutz Sheva gave me a show straight away and I'm still there every week,” he said.

Today, Bingham resides in Jerusalem, where he continues his career and passion for journalism, contributing on the radio and in print to multiple sources on a regular basis.

Bingham expressed grave concern about the current rise in antisemitism globally, and the direction the world is heading.

“Today, we live in a period similar to the 1930s in Germany … and the only difference is that we have the State of Israel and it cannot come to a Final Solution,” he said.

“What is happening everywhere is exactly the same as in the 1930s. Attacks on Jewish property, you name it, and that was happening. And, unfortunately, these various people in each country who are designated to deal with it are not doing very much. It's happening and it can go on until things get even worse. … The countries are not doing enough,” said Bingham.

Modern antisemitism

Bingham also harshly criticized the bias against Israel which is so blatant on campuses and throughout the West today.

“It's so evident that even if we do good things ... look, our water technology is helping the Third World to have water. From the air, we take water now … We help, we get involved. … But that's not talked about. Nothing is mentioned of the good things we do," he said.

In light of the hostility toward Jews on campus today, Bingham urges Jewish students to never stop studying and learning and trying to educate others about Israel.

“They have to fight in universities and schools and talk about [Israel] and try to approach the antisemites,” he said, adding: “It's only education. One has to talk and write and talk. And if students are able to write, if they are capable, put pieces in the local university journal, if they will take it.”

Throughout his 99 years, Bingham has been awarded by multiple armies for his bravery in the face of unimaginable suffering and loss. While Bingham makes it clear he has no warm feelings for Germany, given the horrors of what occurred, it is he who has come out victorious in the end.

This week, Bingham is being awarded the German state of Brandenburg’s highest honor, The Order of Merit of Brandenburg, which the president of Germany and other high-ranking officials bestow on individuals exhibiting remarkable courage. Bingham will fly to Germany to deliver an acceptance speech for the honor just following VE Day – a trip which he says he will use to continue his efforts to educate about antisemitism, Israel and the Holocaust.

If you wish to volunteer with Holocaust survivors or donate click here