Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"Jews shouldn't seek refuge in lands favorable for European settlement, as they would encounter resistance in every such country. They also won't be able to efficiently settle in tropical regions. Given these conditions, Cyprus is the most suitable location for Jewish settlement. While the island isn't a magnet for European settlers, its climate is suitable for Europeans, and notably, it is in close proximity to Israel, serving as a gateway to it."

More stories:

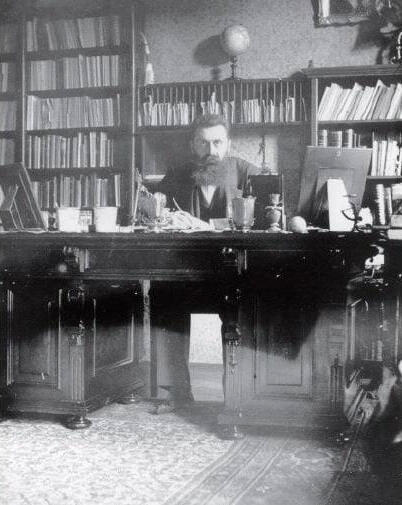

These words are part of a speech by the diligent Zionist activist David Trietsch. In it, he introduced to the Zionist Movement, during the Third Zionist Congress in 1899, the idea that the Jewish state, which Theodor Herzl had dreamed of, would initially be established in Cyprus. Once the situation in Eretz Israel clears up, all Jews from Cyprus would move to the promised land. Trietsch's proposal, aimed at alleviating the plight of East European Jews, was presented with Herzl's consent but was immediately rejected by the Congress's leadership.

Though the proposal for the establishment of a Jewish state in Cyprus was officially removed from the Zionist agenda, Herzl did not forget it. In November 1899, he wrote: "Since the last congress in Basel, there's been a growing fondness within the movement for the island of Cyprus. Given that the Ottoman government shows no inclination to reach an agreement with us, some want to turn to this island, which is under British control and which we could enter at any time. Until the next congress, I still have control over the situation. But if no results are in hand by then, our plans will sink, like water on the island of Cyprus."

Herzl saw Cyprus as leverage to achieve Zionism's primary goal – the Land of Israel. Over time, he even considered that this island, situated close to the shores of Israel, could serve as a literal springboard.

"We would gather on the island, and one day travel to the Land of Israel and reclaim it by force, just as it was taken from us." Alongside Herzl, the persistent and restless David Trietsch continued to advocate for his proposal. With Herzl's consent, he revisited the idea during his closing speech at the Sixth Congress, known as the "Uganda Congress," in 1903.

‘Just a 40-minute flight away’

A Jewish state was never established in Cyprus. Over the years, the number of Jews in the "near-yet-far island" as per Prof. Yossi Ben-Artzi's book, barely reached several hundred.

The most significant change occurred in the 21st century when the number of Israeli-Jews on the island began to rise sharply. In 2003, the Jewish community on the island numbered between 300 to 400 individuals. However, two decades later, the Jewish population, predominantly Israelis, exceeds 12,000. The current monthly growth rate is around 250 to 300 individuals, meaning more than 3,000 Israelis annually relocate to Cyprus.

In every conversation with an Israeli in Cyprus, you'll hear the phrase, "Cyprus is just like Israel, only a 40-minute flight away." Indeed, it's easy to get the impression that this belief is wholehearted. At a resort in Northern Cyprus, we meet an Israeli who states explicitly: "I have a nearly 100-year-old grandmother, a native of Israel, and I frequently fly to Israel just to spend two or three days with her before returning here."

Who are these thousands of Israelis who have permanently relocated to Cyprus? I pose this question to the local Chief Rabbi Aryeh Raskin, and to the director of the Jewish community, Rabbi Levi Yudkin.

Rabbi Raskin responds, "Primarily those who can work from home. Many are high-tech professionals who reside in one of the cities. Unfortunately, some choose to live in rural areas; they can connect to anywhere in the world from their homes, but they're disconnected from Jewish life."

"We meet many Israelis in one of the six Chabad houses on the island," adds Rabbi Yudkin. "We have Hebrew-language kindergartens, a central school in Limassol, kosher food and a synagogue open to everyone. The consistent growth in the number of congregants, 90% of whom are Israelis, is testament to their desire to maintain their Jewish identity."

In the community house courtyard, we join three Israeli kindergarten teachers sitting with fifteen toddlers, engaging them in activities. "Israelis have no other option, especially not during the summer," Rabbi Yudkin says, leading us to the kosher food store in the community house. Most of the dry goods come from Israel, meat and fish from Europe and beverages and wines — some from Cyprus, Italy, France and a few from Israel. "Nothing is lacking here."

When I inquire about the level of security of living on the island, the answer is unequivocal. "In Cyprus, there are no instances of antisemitism. There's no concern about placing a mezuzah on the entrance doorframe. Observant Jews can walk around wearing a kippah, sporting a beard or in traditional attire. The majority of the population highly respects the Jewish people and Israel."

How many Israelis get married in Cyprus each year?

Rabbi Raskin responds that according to the information he has, around 5,000 couples marry civilly, with an additional roughly one hundred Israeli couples that he marries in coordination with the Chief Rabbinate. "I certainly conduct halachic weddings in Cyprus, and I believe those who married through us did so with joy."

The rabbi's room is immaculately clean, and bookshelves lining the walls are filled with texts covering all facets of Judaism. As part of his and the community's activities, he is already planning the establishment of a yeshiva on the island.

Rabbi Levi YudkinPhoto: Dr. Joel Rappel

Rabbi Levi YudkinPhoto: Dr. Joel RappelRegarding the distribution of Israelis across the island, Rabbi Yudkin says, "We don't have precise information about Israelis staying or living in various vacation spots. However, we do know that the largest community resides in Limassol, the economic center of the island, with 800-900 families. In Larnaca, there are 300-350 families, and in significantly smaller numbers in Paphos, Kyrenia, Nicosia and Ayia Napa."

Mother of Jewish settlement

Hidden within a closed-off area on the Turkish side of the island, 10 kilometers south of the Nicosia airport, lies one of the most intriguing tales of Jewish settlement. In this military zone, where stern Turkish soldiers prohibit any visits or tourism, the settlement Margo was established in 1897. While it wasn't the first Jewish settlement attempt on the island, it was the most substantial.

The community, before the outbreak of World War I, consisted of approximately 138 Jewish residents. The agricultural settlements of the Jews, who arrived in Cyprus in 1883 concurrently with the pioneers of the First Aliyah in Israel, are tied to the transfer of Cypriot rule in 1873, from the Ottoman Empire to British imperial control.

The island of Cyprus is effectively divided into two countries: Greek Cyprus in the south, which covers two-thirds of the island's territory, and Northern Cyprus, which is affiliated with Turkey, taking up the northern third. Currently, Rabbi Yudkin notes, most Israelis reside in the Greek part, but there's been a significant increase in the number moving to Northern Cyprus in the past two years. Could we be witnessing the rise of a new Diaspora just a 40-minute flight from home? Only time will tell.

The course of Jewish agricultural settlement between 1883 and 1939 is at the heart of the fascinating research by Prof. Yossi Ben-Artzi in his book "A Near-Far Island". Even though we were warned that we couldn't access the Margo settlement area, formerly known as "Margoa" in those days, we decided to try anyway. However, the taxi driver, with whom we took the Larnaca-Limassol road and who was a Northern Cypriot citizen, didn’t want to participate in an adventure that might end unpleasantly.

The settlement began in 1892 when a British Zionist association, "Ahavat Zion", purchased the lands of Margo. Five years later, in 1898, when 14 homes and an agricultural farm were ready, 12 families from London and Liverpool settled there. They were joined by three instructors from the "Mikveh Israel" agricultural school.

By the start of the 20th century, in 1900, none of those who came from England remained. The empty Margo settlement and its lands were handed over to the JCA company founded by Baron Hirsch, which oversaw the area's resettlement. The days and years following World War I were considered the "golden era" of Jewish settlement in Margo. However, from 1917, it steadily shrank until it was ultimately abandoned in 1927.

In the 1930s, the citrus industry in Israel faced various obstacles that hindered its growth, mainly due to rising land prices and labor costs. In Israel, several groups of agricultural citrus growers took the initiative to plant orchards in southern Cyprus. The largest and most significant of these groups was led by Simcha Ambash, the grandfather of President Isaac Herzog and the father of Ora Herzog and Suzy Eban. This group operated in the citrus sector in the Fasouri area west of Limassol for forty years from 1933 to 1973.

The company planted hundreds of acres of orchards, mainly citrus fruits, interspersed with wind-breaking eucalyptus trees. It established a sophisticated packing house and employed many Cypriot workers, while the majority of the management flew back and forth from Israel. Gradually, the company transitioned to Cypriot ownership. About a year ago, members of Kibbutz Sde Eliyahu, who are establishing a farm for their organic agriculture business, visited the area. They were handed the original ownership documents for the lands of the "Land of Israel-Cyprus Orchard Company Ltd."

Summer and winter camps

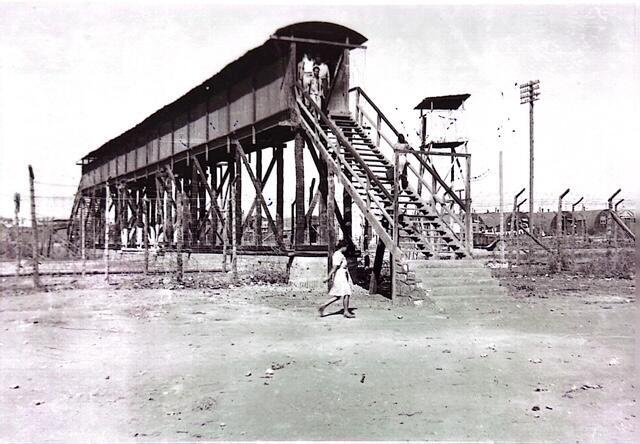

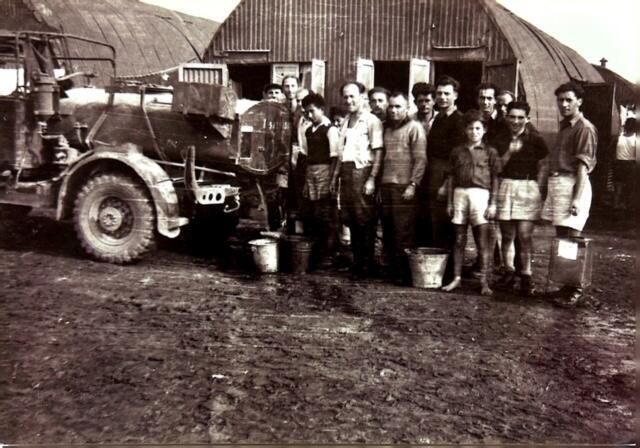

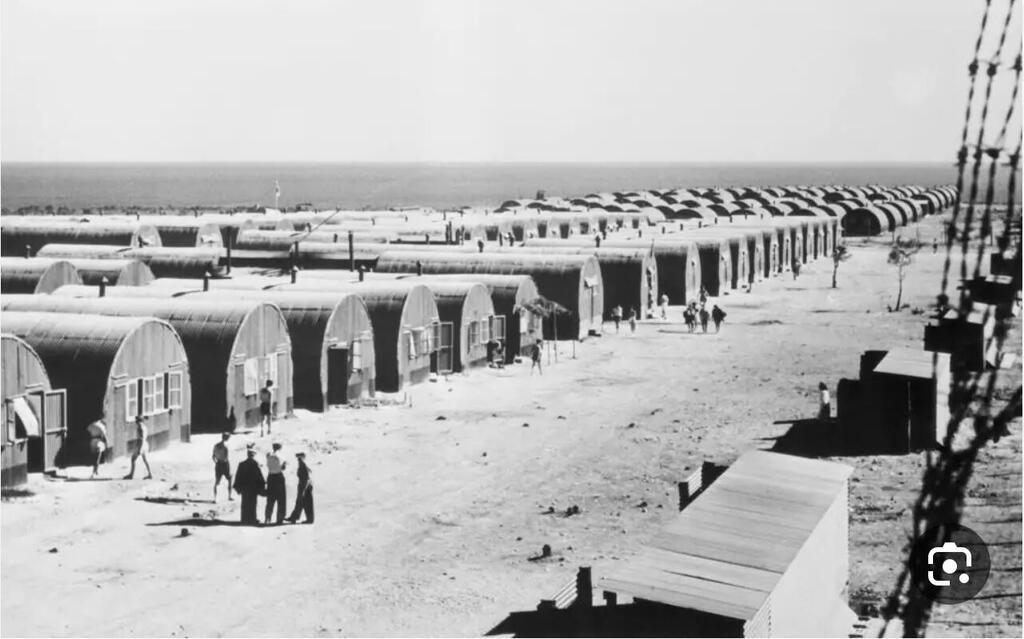

Internment camps for Jewish immigrants in Cyprus were divided into two categories: those with tents were referred to as “summer camps,” and those with metal huts were called “winter camps.” Over the years, a routine developed within these camps as the British Army provided the detainees with water, food, medical care and other daily necessities.

The internment of Jewish immigrants in Cyprus has long been an integral part of Israel's history, especially in the struggle for the establishment of the state. This history is well documented at the Atlit detainee camp in Israel, which was declared a national heritage site in 1987, commemorating the immigrant and Aliyah legacy of Israel.

Life in the internment camps was overseen by representatives from Israel, many of whom were members of various kibbutzim and settler movements. Their primary activities in the camps were organizational, educational, cultural and medical. They established childcare facilities and youth villages, operated schools, founded youth movements, and taught music, crafts, Jewish traditions and about the land of Israel. Through these efforts, detainees were introduced to life and the essence of being in Israel.

Approximately 2,000 children were born in these internment camps. Given that many of the Holocaust survivors faced medical issues, and considering the newborns, there was a higher demand for healthcare than what was provided by the British authorities and military. This gap was filled by doctors who arrived from Israel.

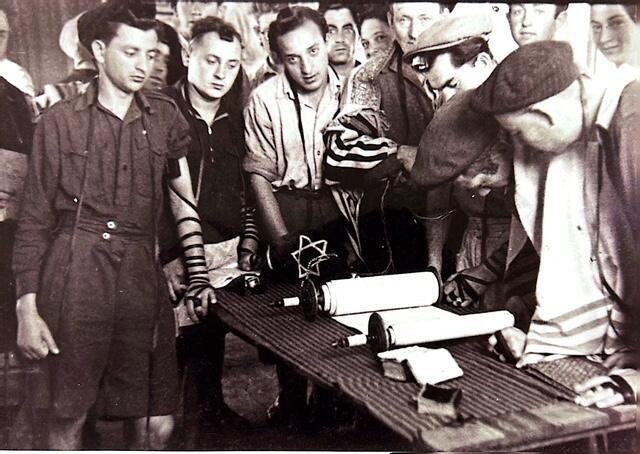

To cater to the many religious detainees, a rabbi operated within the camps; synagogues were built, and halls were set up for lessons on various Jewish topics. As part of the cultural activities, a choir and an orchestra were established, art and sculpture workshops were initiated and various artists from Israel were brought in, including Shoshana Damari, accompanied by Moshe Wilensky.

Upon Israel’s declaration of independence, 4,000 immigrants, mostly women and children, of the 24,000 detainees in the camps were sent to the Holy Land in July 1948.

The British, who had ruled Palestine until May 1948, continued to govern in Cyprus and prohibited the departure of military-aged men between 18 and 45. Their reasoning was that the arrival of these individuals could shift the balance of fighting forces in Israel. The last of the detainees were brought to Israel in February 1949.

In recent years, a museum called the Haapalah Museum was established in Larnaca, Cyprus, adjacent to the Chabad House and the Jewish community center. At its heart is an original metal barrack that's 77 years old, which was unexpectedly discovered at one of the internment camp sites.

With special permission from authorities, the Jewish community was allowed to move the barrack to Larnaca, with the specific purpose of creating a museum dedicated to the internment camps. We visited the museum under the guidance of a British Jew named Aryeh Cohen, who has been devoted to documenting the history of these camps for several years.

Upon entering, we immediately noticed a mezuzah at one of the camp sites. As we opened the wooden door of the metal barrack, we were introduced to a museum showcasing a special exhibition on the "Cyprus Camps." This exhibit was recently prepared by Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, a group dedicated to documenting the Holocaust and the world of devout Jews during that period. Rabbi Tzvi Skolski from the Bnei Brak-based group informed us that over the years, they have managed to collect hundreds of original photos and numerous documents related to the Cyprus camps. They were delighted to accept the proposal to create a dignified and impressive exhibition from which one can visually learn about those years, 1946-1949.