Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Recently, we learned of another huge acquisition deal by the Defense Ministry in which Lockheed Martin will produce eight additional Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion helicopters for Israel. This deal joins the purchase of 25 F-35 aircraft from the American company for a sum of about 3$ billion, thanks to Pentagon aid funds.

Read more:

For the average reader, the magic words "CH-53K King Stallion" and "F-35" overshadow any sum, however incomprehensible it may be, but not many are aware that behind the numbers lies a handsome profit margin that comes long after the cameras are turned off and the headlines change.

11 View gallery

TransDigm is a manufacturer of spare parts for Apache helicopters (top right), Boeing co-produced the Arrow 3 missile with the Israel Aerospace Industry (bottom right), Raytheon produces Israel's Patriot missiles (top left), and Lockheed Martin supplies Israel with F-35 aircraft (bottom left)

(Photo: Israel Aerospace Industries, U.S. Army, Lockheed Martin, EPA)

Big defense contractors enjoy the glamour of manufacturing aircraft, submarines and advanced missiles but mounting evidence shows that their large profits actually come from much less "impressive" products—spare parts like valves, oil pipes, screws and nails that would cost you only a few hundred dollars on the shelf, but are sold to the Pentagon for inflated sums in the many thousands.

This cost, of course, is passed on to the U.S. taxpayer, and to countries that receive American aid funds, like Israel. There is also an impact on the military capabilities of these countries, which ultimately have to divert resources for spare parts at extortionate prices, instead of vital acquisitions.

‘Tricking the establishment and dramatically inflating the price’

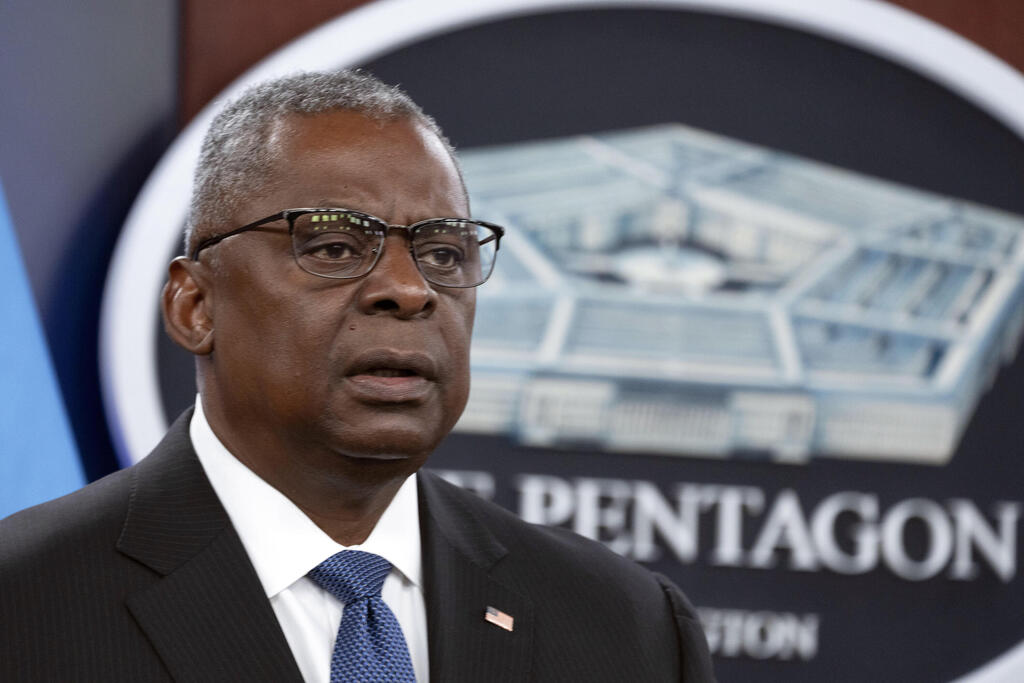

In a letter sent last May by five senators to U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, they demand answers regarding the inflated pricing methods of large defense contractors, including Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon and TransDigm.

In the scathing letter, they argue that while the permissible profit on Pentagon contracts for spare parts is supposed to be 12%-15%, these contractors manage to systematically game the system and lock in profits ranging between 40% and 50%, and in some cases, even up to 4,000%.

“Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, and TransDigm are among the offenders, dramatically overcharging the Department and U.S. taxpayers while reaping enormous profits, seeing their stock prices soar, and handing out massive executive compensation packages,” they wrote.

“These companies have abused the trust government has placed in them, exploiting their position as sole suppliers for certain items to increase prices far above inflation or any reasonable profit margin.”

All the companies in question have extensive connections, representations or subsidiaries in Israel, selling to the Defense Ministry, the Air Force, military industries, Rafael and more.

For example, Raytheon produces Israel's Patriot missiles and, together with Rafael, also produces the Iron Dome. Lockheed Martin Israel, with the help of its management staffed by Air Force veterans, has become the IDF's largest supplier in recent years with deals involving F-16s and CH-53K King Stallion, Yas'ur helicopters, and Black Hawks. Boeing, in collaboration with the aviation industry, produced the Arrow 3 missile and has provided the Air Force with F-15 aircraft, as well as "smart" bombs (JDAM).

The fourth name, TransDigm, is perhaps less familiar than the others (part of its marketing strategy, which we will return to later), but it manufactures spare parts for Apache helicopters and F-16 aircraft and has managed to turn the method of inflating aircraft component prices into a genuine business model.

CEO Nick Howley has already been called twice to testify before Congress on charges of price gouging after the Defense Department's investigative team found that the company charged $119 million for spare parts that were supposed to cost $28 million—essentially, a fourfold markup. This may explain the company's astonishing profitability and the fact that Howley earns more than the CEOs of Lockheed, Boeing and Raytheon combined.

Sources within the companies we spoke to argued that the numbers cited in the senators' letter are exaggerated. They say that since 2015, the Pentagon has even been directly involved in their contracts with subcontractors in order to make the negotiations more transparent.

"So why would it shoot itself in the foot?" they wonder. No one is trying to swindle the Pentagon, the company clarifies, and according to them, no one seriously thinks that this is the main source of the contractor's profits.

They further argue that the U.S. government is heavily involved in every procurement process and that they "can't do anything without approval from the Department of Defense."

Raytheon did not respond to our request for comment, but after the Justice Department launched an investigation against them, the company admitted to inflating the prices of Patriot missiles. However, they dismissed the allegations by claiming that these were one-time incidents, "that should not have happened, but did," according to CEO Gregory Hayes.

Monopolistic market and less oversight

The pricing method of the companies is the same in all the countries where they operate and for all customers, certainly when it comes to American aid money in which the Pentagon is involved. So, why has this whole affair flown under the radar?

One reason is that in the United States, as in Israel, when it comes to matters of national security, things quickly move into the shadows, and no party, whether involved or uninvolved in the process, really understands what is happening on either side. At least until one brave "whistleblower" comes along to shed some light on what it looks like from the inside.

In our case, Shay Assad (ironically, not Israeli), served in the highest position responsible for Defense Department contracts. Assad earned the nickname "the most hated man in the Pentagon" after his investigations led to massive cuts amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts with defense contractors.

His name preceded him as the most decorated professional in the field of procurement and pricing in public service. Despite all this, he too was unable to clean up all the irregularities and decided to turn to the media after retiring.

Assad pointed to cases of extreme price gouging by suppliers, leading to the Pentagon paying too much for almost everything: from missile systems and submarines to simple components like nails and bolts.

His motivation wasn't just about financial corruption: the moment prices are inflated and resources are diverted away from essential procurement, the impact on military readiness is inevitable. In his view, the maneuvers and manipulations of the contractors lead nations and armies to make difficult budgetary choices, and ultimately to a soldier left on the battlefield, quite literally, with a gun but no bullets.

In 2006, the U.S. wanted to send Apache helicopters to Iraq, but they couldn't fly without a vital valve. Meanwhile, TransDigm, in what would later be revealed as a business model, took over the authorized manufacturer of the valve and hiked the component’s price by about 40% to $747.

The Pentagon made it clear to the company that the helicopters were urgently needed on the battlefield, but according to a Pentagon report, TransDigm didn't even blink. By 2018, the price of the valve had jumped to around $12,000, in what the Defense Department called nothing short of "extortion."

How does all this happen in a free market economy like America? It turns out that when it comes to national security, the market suddenly becomes much less capitalistic and much more monopolistic.

The roots of the problem can be traced back to 1993, when the Pentagon sought to cut costs and pushed defense contractors to merge. Fifty-one major contractors were consolidated into five arms giants, and the intense competition of the 1980s gave way to monopolistic forces that severely limited the bargaining power of buyers. This was compounded by extensive cuts to the U.S. defense budget, which reduced oversight and allowed contractors to exploit their status to hike up the prices of exclusive products.

The company dubbed ‘The Devil of Spare Parts’

When defense contractors supply new combat equipment, they usually also sign a maintenance and spare parts agreement – as was the case with Lockheed's F-35 deal announced in July.

11 View gallery

Israeli F-35 fighters during a joint military exercise with the US Air Force

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

As the years go by and the fleet becomes older, spare parts become increasingly rare. Suppliers who know how to produce them have to go through stringent regulations—every single part of the aircraft, down to the last valve, has to undergo meticulous safety inspections and quality control processes. Very few suppliers are knowledgeable and capable enough to navigate through this process. And those who do—exploit their unique position at the top to maximize profits.

And this is actually a method that TransDigm has perhaps elevated to an art form. It's no coincidence that the company earned the nickname "The Devil of Spare Parts" or alternatively, "a malignant cancer."

If the brand name doesn't say much to you, it's because the company, based in Cleveland, Ohio, is actually a conglomerate that brings under its umbrella dozens of independent companies around the world.

Since its establishment, it has managed to acquire more than 88 different companies, including ScioTeq Ltd (formerly Esterline), which had a branch in Rishon Lezion and sold professional control and monitoring screens to security forces in the fields of aviation, sea and land.

Pentagon investigations revealed that TransDigm made a profit of 4,436% on a coupling for a passenger plane, for example, charged $4,361 for a half-inch pin that was supposed to cost $46, and charged $10,000 for a hydraulic valve that was supposed to cost $641. All of this was done ostensibly legally, but the company's convoluted business maneuvers managed to arouse both outrage and considerable interest.

After all, the founder and CEO didn't come up with this scheme. He followed in the footsteps of his father, the president of Lansdowne Steel & Iron, which produced military equipment for the American army until it too was accused of price gouging in 1971.

Since TransDigm's IPO on the New York Stock Exchange in 2006, the CEO's net worth is estimated to have catapulted to $1.1 billion. He himself encouraged the company's salespeople to meet sales targets at inflated prices, as revealed by internal company emails submitted to Congress.

In one correspondence, the CEO warns the company's vice president not to "underestimate the laziness" of Pentagon officials in order to push them to favor sales recorded in the current quarter instead of the one after, to please the investors.

In other astonishing emails, the company's salespeople brag about how they lied and withheld information from Pentagon officials in order to inflate prices and exploit the public coffers.

"I'm just full of crap and they swallowed the bait," writes one of the salespeople to a colleague. An entire presentation called "The Art of Price Defense 101" was distributed to the sales team to train them in justifying the inflated prices.

While some people may certainly see TransDigm's pricing strategy as corporate greed and avarice, its investors see it as a brilliant business model. The company's stock has provided exceptional annual returns since its initial public offering, making it a central candidate for any investor looking for strong returns.

Despite investors' jubilations, price gouging comes at the expense of taxpayers and could also inflate security expenditures by billions over the years.

These aggressive pricing methods resonate at a time when Israel, which relies on U.S. military aid, is negotiating with the Pentagon over contracts for equipment and security systems.

How does the method work?

Acquiring companies in monopolistic positions: TransDigm's strategy starts with the acquisition of companies that produce specialized aircraft parts or those with patent rights. These are parts that other suppliers either don't know how to or cannot produce, but they are critical to the functioning of aircraft systems. As a result, TransDigm can corner the market for specific parts.

Lack of alternatives: Due to stringent regulations and safety standards in the aviation industry, every small plane part— from the lock on the door to valves and water pipes— must be approved as safe for use by various aviation authorities around the world. This approval process is expensive, time-consuming and requires significant resources from manufacturers.

Once the parts are already approved and integrated into the aircraft, clients are hesitant to quickly switch them out for alternatives and face the costs and risks associated with undergoing the re-approval process with authorities. This lack of choice gives TransDigm significant bargaining power in negotiations over prices.

Aftermarket dominance: The aftermarket, meaning the spare parts required for the maintenance and repair of older aircraft—those that continue to fly long after their year of manufacture—constitutes TransDigm's main source of income.

When the parts are first produced as part of a comprehensive aircraft purchase package, the prices are usually competitive because the manufacturers want to close the big deal.

Years later, when the original manufacturers are out of the picture and no longer selling the aircraft, TransDigm steps in and can demand much higher prices than the original.

Aviation companies or security forces essentially have to purchase these parts to keep their planes operational, leaving TransDigm with the upper hand in wielding its bargaining power.

Aggressive pricing: History shows that the moment TransDigm acquires a company and takes control of its patent-protected parts production, it typically also significantly hikes up the prices of said parts. This is possible because it serves "captive customers"—aviation companies and military organizations that are required to use these parts due to regulations and the need for compatibility with existing systems.

This allows TransDigm to hike prices without the fear of losing customers to competitors. TransDigm's strategy also includes immediately raising prices after acquiring a company, leading to a rapid increase in profits and a healthy profit margin in subsequent financial reports.

This way, it can actually capitalize on increased revenues to show strong financial performance, thereby boosting stock prices and attracting investors. Former employees have described the method as lacking any tact or regulation, and have raised concerns about dubious accounting practices.

Lack of transparency: One central aspect of TransDigm's strategy is its resistance to disclosure and detailed sharing of production costs. It relies on state secrets privilege to keep its cards close to the vest, preventing clients and even the Pentagon itself from accurately assessing whether the prices it charges are fair and reasonable.

This lack of transparency hinders the ability to negotiate better deals with it and has reportedly even reached the U.S. Congress, which claimed that the company is not acting as a partner but rather with a predatory approach.

Israeli government’s new strategy?

Ultimately, TransDigm's method exploits the complex regulatory landscape of the aviation industry, the critical need for aircraft parts and the lack of alternatives for these specialized components. While the strategy does attract criticism for inflating costs for both military and commercial aviation companies, it has also proven to be very profitable for TransDigm and its investors.

While the company continues to tread the fine line between legitimate profit-making and unethical business practices, the global aviation industry watches helplessly from the sidelines. Although TransDigm's innovative business model has propelled it to financial success, the ethical implications and the impact on security budgets cast a shadow over its achievements.

The controversy surrounding its business practices extends beyond corporate profits and beyond U.S. borders. It affects how governments, including Israel's, and global security agencies assess and negotiate their defense contracts.

11 View gallery

Defense Minister Yoav Gallant and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

(Photo: Amos Ben Gershom/GPO)

It's no longer possible to ignore the tactics, and it may be that the Israeli government and other global security bodies will need to rethink how they assess and manage negotiations for contracts with companies like TransDigm in order to ensure efficient use of taxpayer money.

Comments:

Boeing: “We take very seriously our responsibility to support the warfighter and our commitments to the Department of Defense.”

Lockheed Martin: “Lockheed Martin constructively and ethically works with the U.S. government to support its national defense, intelligence, and international security cooperation objectives. We negotiate with the government in good faith on all our programs to meet its mission needs with the best and most effective technologies and systems in compliance with Federal Acquisition Regulations and all other applicable laws.”

Pentagon: "We refer you to Israel and the specific defense contractors you describe below for these questions."