Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Just before the war, attorney Moran Gez, 46, was planning to leave the Southern District Prosecutor’s Office and dreaming of starting her own private practice. “Then October 7 happened, and I immediately told myself, ‘Put your plans aside.’ I sent a message to the district attorney: ‘I’m here. Whatever is needed, I’ll do it.’”

Gez, a prosecutor with over 20 years of experience, had recently overseen security-related cases in the Southern District. She led high-profile cases, including the murder trial of Ron Kokia, who was killed in 2017 by Khaled Abu Jaudah, later sentenced to life in prison.

Her last security case involved ten defendants, both Israelis and West Bank residents, accused of attempting to form a terrorist cell aimed at attacking Israelis and assassinating National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir. An indictment was filed this past April, but the trial has yet to begin.

Gez was one of four attorneys appointed to a specialized October 7 legal task force. "When I was sent to the first meeting at Lahav 433 with all the investigation teams working on the issue, I walked into a huge hall. There were maybe 50 people there—members of the National Fraud Unit, the Anti-Corruption Unit, the Serious Crimes Unit, Etgar and Unit 103. They came prepared. Each one had a specific area of responsibility, a designated task. They were completely ready. And I looked around and thought, 'Wow, we’re just four prosecutors handling this.' At that point, we already knew there were 1,100 victims and hostages. How could we possibly manage this? It was overwhelming."

Gez criticized the slow pace of the process, citing several reasons: a lack of manpower in the prosecution, delays in enacting necessary legislative changes and an absence of solutions for the enormous number of potential defendants.

"When we started dealing with this, we were told indictments would be filed within a year, but even now, no decision has been made. From colleagues and lawyers involved, I hear it’s still far off. Meanwhile, the detention of the terrorists is extended every few months. Now it’s been extended until March next year. I don’t see indictments on the horizon."

"There was also a sense that the state didn’t believe it needed to allocate additional manpower to the prosecution for this task. So, they pulled two prosecutors from each district office because we couldn’t handle the workload. Today, the team has grown to about 20 prosecutors, but most of the original prosecutors from other districts who handled these cases from the start eventually left—like me."

The blood must not cool

The biggest challenge is evidence, Gez explains. Linking specific crimes to specific suspects, across dozens of crime scenes involving hundreds of suspects and thousands of offenses, is nearly impossible. "Standard rules of evidence don’t fit this situation. There are no organized chains of evidence, and there’s no one to verify the videos you want to present in court.

"Legislative amendments are needed; otherwise, it’s impossible to handle these cases. But even legislative changes can’t be applied retroactively, so that won’t fully resolve the issue. What’s needed is a comprehensive legislative reform regarding evidence to allow for filing indictments. I hope that’s being worked on, but everything is moving far too slowly."

So what’s the solution?

"In the end, you need a confession in a case like this. You need each individual to recount their role to build a complete narrative of the location—how many terrorists were there, what they did, what the premeditated plan was and how far in advance they knew about it. All of this is crucial from an evidentiary standpoint.

"But surprisingly, in the interrogations of these terrorists, they try to downplay the nationalist aspect. From my experience with security cases, most terrorists are very proud of what they’ve done and don’t hide it; they even openly tell investigators they’re proud. On October 7, you could see from the GoPro footage how motivated and ideologically driven they were. Yet, in practice, most of the terrorists from October 7 turned out to be cowards. In the interrogations, no one admits to actually shooting: ‘I fired and missed,’ ‘I was injured as soon as I entered the post,’ ‘My weapon jammed.’ I’m not used to seeing terrorists behave this way."

One reason for delaying prosecutions is the effort not to jeopardize the chances of the hostages’ return. Another reason is the concern that Palestinians and European human rights organizations might ramp up initiatives for legal countermeasures against Israel.

In the meantime, alternatives are being considered, such as establishing a special tribunal for the massacre’s perpetrators or granting jurisdiction over the matter to the military court in Lod, which was closed in 2000 and previously dealt with cases involving threats to national security.

“The best option would have been to establish the military court,” says Gez. “But a different decision was made. We also need to think about who will represent these individuals in the end. How will the trials be conducted? Individually? And how will you bring them to court? You’ll need a hundred attorneys, and there are conflicts of interest. These are issues that need careful consideration.

“At that first meeting, the head of Lahav 433 [Israel Police’s serious crime unit] asked me, ‘What should the indictment look like?’ I told him, ‘What do you mean, what? Anyone who crossed from Gaza into Israel on October 7—whether to kill or loot, it doesn’t matter—should be included in the indictment and, as far as I’m concerned, receive the death penalty.’

“Why? Because those who didn’t kill but looted, burned, stole or even picked avocados, as some claim, stirred such chaos that held back the IDF from arriving on time. If you came with a drill to open a door for looting, and then a terrorist entered and murdered civilians, the state should hold everyone accountable. We won’t succeed in sorting these people out because they all contributed to this massacre in the end, even if the conspiracy was spontaneous and only happened when they breached the border. And I must say, everyone in that discussion supported this approach.”

It was two weeks later. The blood was still boiling.

“I don’t think the blood should have cooled during the time that’s passed. We need to remind ourselves of the horrors that happened there. I’ve completely lost any compassion for these people. It doesn’t matter what you did—if you were detained on October 7, as far as I’m concerned, you have no right to live. You won’t find an ounce of mercy in me. I’m sorry.

“In past security cases I handled, there were Gaza residents accused of more ‘civil’ offenses, like smuggling. Those were people I felt sympathy for—individuals trying to support their families and even bringing equipment into hospitals. But those same hospitals ended up receiving the hostages and hiding terrorists. On October 7, we saw crowds in Gaza dancing on corpses, and so the compassion diminishes.”

So, the death penalty for everyone?

“As far as I’m concerned, yes. Today, there are offenses that allow for the death penalty, like aiding the enemy during war, harming sovereignty or causing war. But legally, we’ve only done it once (against Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, who was tried and executed in Israel). Honestly, I don’t think there’s any chance of someone here filing an indictment seeking the death penalty, and I don’t think there’s any chance a court would impose it.”

Sleeping with the testimonies

Gez’s role primarily involved reviewing the investigation materials related to the terrorists. “A terrorist’s name would come up, and I would go through the initial materials and the suspicions against them to determine which location they were connected to.

For example, if a terrorist mentioned seeing the sign for Sderot, I would piece it together and figure out what follow-up investigations were needed. We created an investigative protocol for the police, and then the case would be passed on to a prosecutor to summarize the findings. As the number of terrorists grew, it became harder for me to keep track of them all.

“At night, I would sit there like a junky, reading the materials. My parents, my ex-husband—everyone pitched in to take care of the kids. I would come home late, sit in bed and read the new reports that had come in. More and more and more. It became my entire life. Testimonies from ZAKA, the Chief Rabbinate, the women who washed the bodies. And when I wasn’t reading, I was watching the news on TV, looking for clues on where further investigation was needed. It felt endless, something so massive it was impossible to control. I would go to sleep with the testimonies and videos on my mind, constantly afraid that if I didn’t read everything, I wouldn’t know what was missing.

“It was the small things that shook me the most. I saw a video of a mother with her children in a safe room. The child was young, about the same age as my son. You see him bleeding, and she’s whispering to him that everything will be okay. And you can see it won’t be. It’s not okay. She loses him, utterly helpless, unable to do anything except record and whisper softly.

“At some point, I developed fears. I ordered window bars for my home, even though I thought, ‘What good will bars do?’ Strangely, when I visited the Gaza border communities, it actually calmed me down. It showed me that survival was possible.”

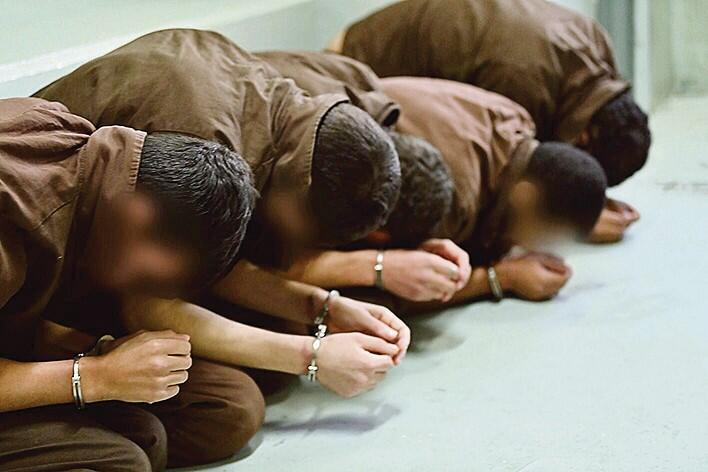

They are placed in the category of unlawful combatants, under administrative detention, with their detention extended every six months because there aren’t enough prosecutors to handle these investigations.

She was also responsible for handling sexual offenses. “Unfortunately, it will be very difficult to prove these crimes,” she says. “In the end, we don’t have complainants. What was reported in the media compared to what will ultimately be established will look very different—either because the victims were murdered or because women who were raped are unwilling to come forward.

“We reached out to women’s rights organizations and requested cooperation. They told us no one had contacted them. Some parents reached out to these organizations, asking what to do if something happened to their daughters, but they didn’t disclose the assaults.

“In this area, I would temper expectations. I know the public is expecting action and understands the need to address the horrific sexual offenses and assaults that occurred, but the vast majority of these cases won’t meet the evidentiary threshold in court, and the criticism will ultimately fall on the prosecution—unjustly so.”

The already overwhelming workload was further compounded by detainees captured after IDF forces entered Gaza. “The issue of maneuver detainees—people who planted explosives, killed soldiers, fired rockets, killed civilians and confessed to it—isn’t being addressed right now. They are placed in the category of unlawful combatants, under administrative detention, with their detention extended every six months because there aren’t enough prosecutors to handle these investigations.

“They are interrogated by the police, but no prosecutor is reviewing the material, requesting follow-ups or completing the investigations. If at some point, years from now, the prosecution has time to deal with these cases, any follow-ups will be irrelevant. In other words, these individuals will likely never face trial and won’t be held accountable for their actions—and that’s simply the result of the decision not to allocate additional budget or positions to the prosecution, which is already stretched to its limit.”

Seven complainants a week

Gez is one of more than ten prosecutors who left the Southern District Attorney’s Office in the past year—one of the most overburdened legal bodies in Israel following the October 7 massacre.

This departure comes despite the recent addition of eight new positions to the office, which are still insufficient to handle the workload in a district that covers more than 60% of the country’s land area.

Despite her frustration with the job, Gez achieved significant milestones. In the high-profile attempted murder case of Shira Isakov, where she served as prosecutor, she established a precedent that will impact future domestic violence cases. Aviad Moshe, Isakov’s ex-husband, was sentenced to 23 years in prison after being convicted of attempted murder and child abuse—despite not physically harming his son.

On October 6 of this year, exactly one year after the war began, Gez opened a private law practice with a colleague. “For years, I had no life. I was working under insane pressure. The work in the prosecution is exhausting and intense. There was a time I had to interview seven underage complainants in a single week. That’s not normal. You can’t prepare for court that way. And in the end, this is a matter of life and death—both for the defendant, whose entire future is at stake, and for the complainant. Many times, I felt that no matter what I did or how late I worked, I couldn’t do my job the way I wanted. I just couldn’t take it anymore.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“There’s currently a huge shortage of prosecutors in our office, especially experienced ones. The situation keeps getting worse, and it’s a vicious cycle—fewer people share the burden, more people collapse under the pressure, and even fewer want to stay in the prosecution. But you can’t only blame the system. October 7 also made people rethink their lives and what they want to do—to spend more time with their kids and families. Because you see how, in an instant, everything can disappear.”