Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

At the age of 83, Tom Stoppard, one of Britain's greatest living playwrights, wrote Leopoldstadt, a play about the end of Jewish life in Europe, the illusion under which Jews lived then and how Jews live today in Europe, and the Zionist solution.

Read more:

Leopoldstadt is currently showing at Tel Aviv’s Habima Theater, in a relatively small hall, as was previously shown in London and New York. It tells the story of a wealthy and partially assimilating Jewish family, the Merz family, in Vienna during the first half of the 20th century.

2 View gallery

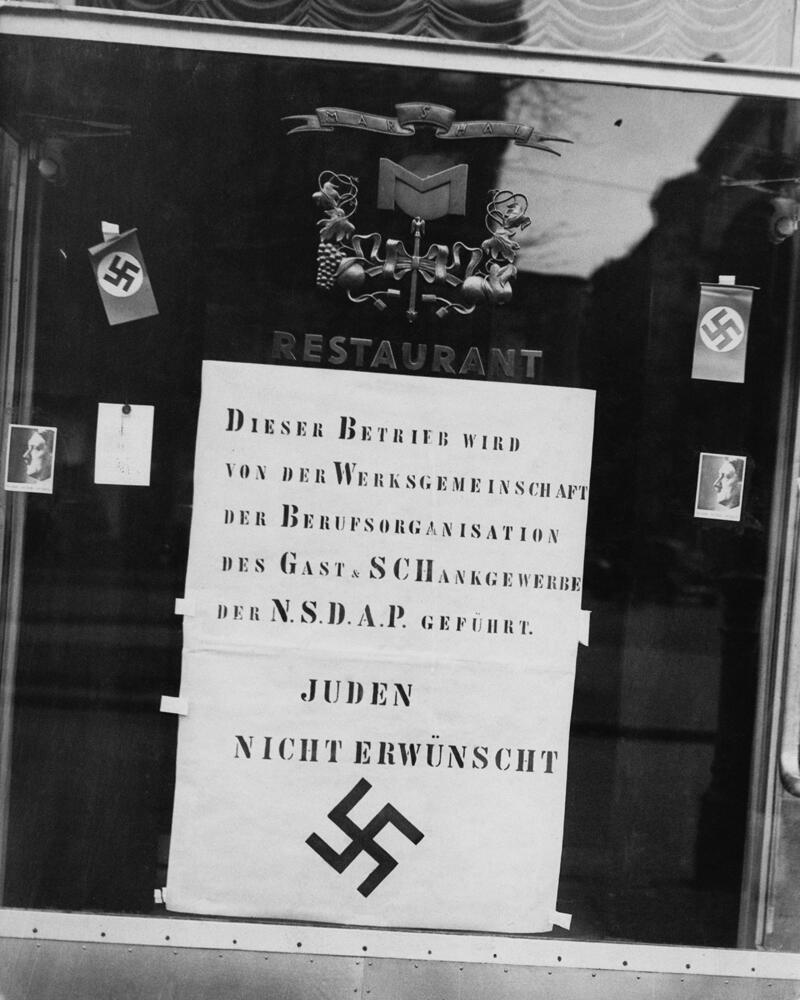

Austria had a Jewish population of some 185,000 before Nazi German soldiers marched in to annex the country in 1938

(Photo: AFP)

On the eve of Austria's willful annexation to Nazi Germany in March 1938, or the Anschluss, Vienna's Jewish population stood at approximately 185,000. The old aristocracy resided in luxury quarters, and immigrants from Eastern Europe crowded in the second quarter, "Leopold City" – Leopoldstadt, named after Emperor Leopold I.

The Jews of Vienna back then made up three-quarters of the prominent writers, leading cultural figures, scientists and opinion leaders of Austria. In one of the early scenes of the play, the family patriarch Hermann Merz proclaims, "Here is our promised land."

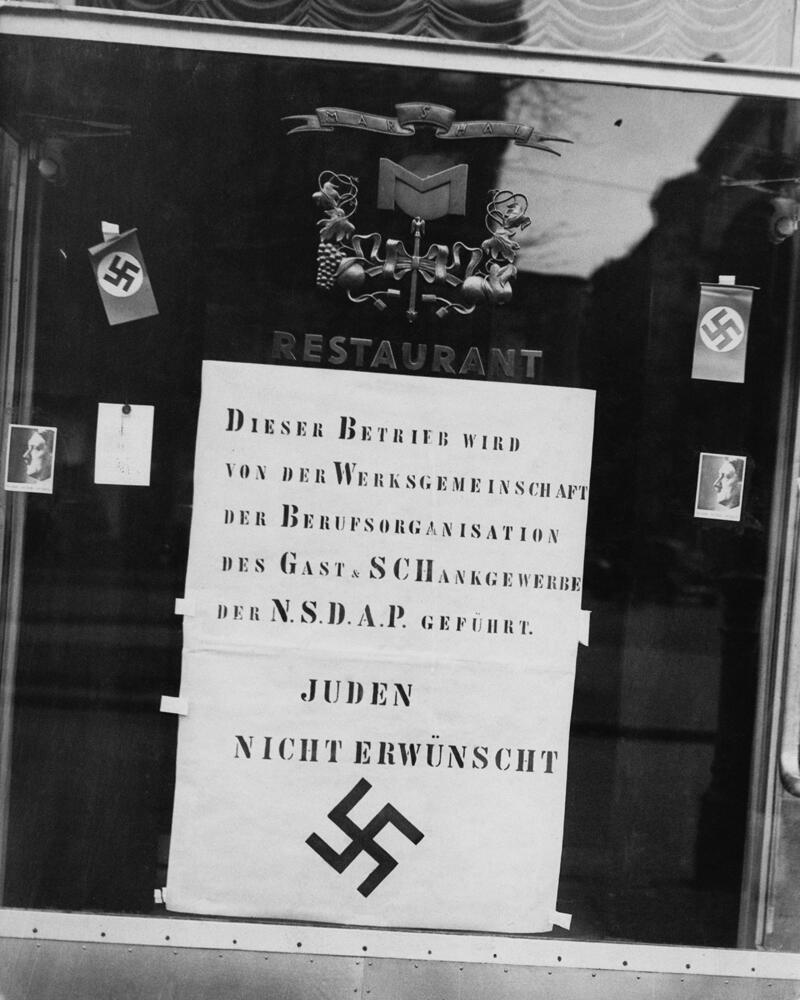

Apparently not. After the pogrom in the week of the annexation to Nazi Germany, during which cultured Viennese residents plundered and beat their Jewish neighbors in a relentless riot, they seized their property and deported them from their homes to the ghetto - finally, the local Jews understood that they were "unwanted strangers in their land."

The Jewish Community of Vienna (IKG) managed by the end of 1941 to save no fewer than 136,000 Jews who found refuge outside the borders of the Third Reich. The remaining 50,000 were sent to extermination camps from 1942 until the end of 1944. I have had the opportunity in the past year to visit Leopoldstadt several times. Among the hundreds of massive buildings, which the Vienna municipality has renovated, I did not find a single one with a memorial plaque to the Jews who lived here in large numbers.

2 View gallery

A sign saying 'Jews aren't welcome' in Vienna, Austria, after the Anschluss

(Photo: Gettyimages)

One percent of Vienna's Jews immigrated to Israel. However, the Zionist motive appears throughout the play. "The Jewish people without a state of their own," declares Ludwig Merz, a leading figure in the family, "will always remain outsiders, obviously." Another family member adds, "Jews will become a normal people only when they have a state."

The chilling final scene takes place in Vienna in 1955, with the signing of an agreement to renew the sovereignty of the Austrian state. The cultural world finally adopted the narrative according to which Austria and its inhabitants were "innocent victims of the Nazi German invasion." Their hands did not spill the blood of the Jews, even though "half of the extermination camp guards," says Nathan, one of the few survivors, "were Austrians... Antisemitism in Austria is now a political fact." The play ends with the recitation of the names of the murdered family members in Auschwitz, Dachau, the death marches and death pits.

In an interview with The New York Times last year, Stoppard said that antisemitism is “like a latent virus that becomes activated under certain conditions.” For him, hatred of Jews is deeply rooted in the consciousness of the Western man. The possibility to "create a society where you don’t have to deal with antisemitism because it’s simply not part of anybody’s consciousness,” Stoppard defined as "Utopian."

The theater critic of that same newspaper Jesse Green wondered who the play is intended for. Well, it is intended for Jews who are trying their best to erase the memory of antisemitism from their consciousness and to convince themselves, like the members of the Viennese Merz family, that "this could not happen to us." Beware, warns 86-year-old Stoppard, the specter of antisemitism is alive, breathing and always ready to pounce from its latent state.