Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The academic year in the U.S. is coming to a close. In a few weeks, University students in the graduating class will gather on the lawn, in their robes and caps. They will pose excitedly for pictures, shake the hands of deans, and then fly off, making way for a new generation.

As graduation ceremonies near, so do anti-Israel protests on American university campuses. I can begin sounding the all-clear. Here at Stanford, at least, the students camping out on the lawn call for "global intifada,” pose no physical danger. But in the medium to long term, they are very dangerous to the character of the leader of the free world.

Columbia University 17-24.4.2024

This is my second year at Stanford. When we came back to school in September, after the summer vacation, I intended to end the year with an accepted research proposal and a third of my PhD thesis already written. It is hard to describe how far I am from those goals. In my view, I am no different than others. Since October, many Israelis studying abroad found that they had a choice of two options – their heads down or becoming ambassadors of Israel.

With two brothers fighting in Gaza, who would be able to sit down and write a paper. So instead, I found myself spending most of my time "explaining" Israel, something I had not intended to have anything to do with at Stanford.

Despite that, I did learn a few valuable lessons this year, that would be remembered for life. As the academic year ends, as amid the worries and concerns from home over the current madness on campuses, I thought I would share the five most important lessons I've learned this past year at Stanford University in California.

1. Whether we like it or not, we are always, first and foremost, Jews.

My first year here was a most powerful academic experience. I felt surrounded by friends from around the world. I had full access to the brightest legal minds in the world. The feeling was that I had at my disposal endless opportunities. Friends from Israel who asked last year if we suffered from anti-Israel sentiments, seemed laughable. What are they talking about? I am a liberal Israeli. I wrote for the most left-wing Israeli newspaper. I clerked at one of the most liberal Supreme Courts in the Western world. Why should anyone have any problem with me?

I moved among those I believed were my friends as an equal. I could speak freely about Israel, criticize it and love it, have what I believed were good and complex discussions about the most sensitive matters, even with those who clearly did not agree with me. I felt like I was a citizen of the world.

That was an illusion. There is apparently, no such thing as "a Jewish citizen of the world," as long as the Jew insists on his right to a national homeland.

When push came to shove, very few stood beside me. Almost none of them stood with me nationally. The double standards enabled Israel-hating students to say terrible things about me and my friends but silenced any of our attempts to push back. In some places, I had to choose between apologizing for being Israeli, or being rejected. There was no dilemma.

This eye-opening experience had its advantages. It was a litmus test of the human quality of those around us. Some went out of their way to support me, or to exhibit gestures of humanity. I found I was surrounded by strong and durable ties. Those are friends I would not forget easily.

2. America deserves Donald Trump.

A friend joked that if Trump were to be re-elected in November, he would walk around the Stanford campus handing out candy, as an act of celebration. He laughed because this is not entirely unimaginable.

Like many around the world, I was dumbfounded on November 9, 2016, when the United States of America elected Donald Trump as president. It was unfathomable to me in the deepest sense, despite the articles I read and the documentaries I watched. The appointment of this man was inexplicable, unreal, impossible. Even years later when the words President Trump no longer felt strange to utter, his election remained a mystery. A glitch in the matrix, I could not understand how his campaign was successful.

This year I understood. And no. If I were an American, I still would not vote for Trump but I do understand now, those who do. Donald Trump is the reaction of some Americans to the madness we are witnessing. A madness I was unaware of until it turned on us. Madness that is no less bad. No, if I had the right to vote, I would not choose Trump. But America, in a sense, tragically deserves him.

3. Progressives are not political allies of liberal Zionists.

Last year, the progressive movement appeared to me to be an amusing youthful rebellion. The ceremony where everyone announced their gender at the beginning of class seemed strange, not always necessary, but harmless. The fact that I had to state my race on every form (I said I was Middle Eastern) made me laugh, but raised no resistance. I regarded the American progressive movement, as the childish little sister of the liberal movements that I respected. I saw it as an ally. That was a mistake.

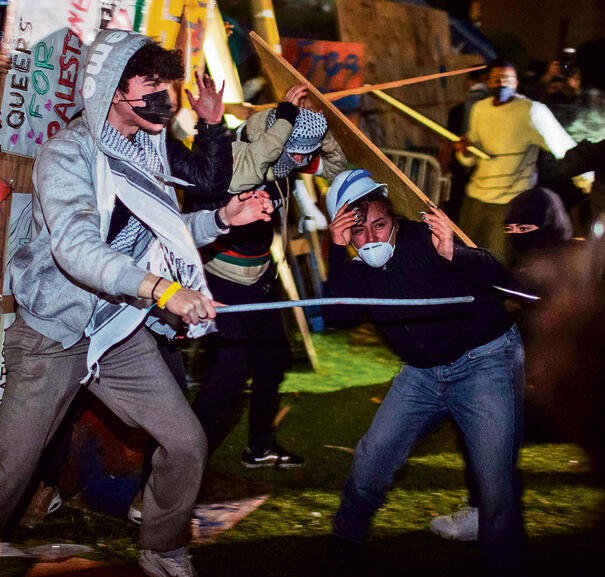

The progressive movement is not an amusing anecdote. This week I witnessed an especially graphic expression of that. In the "pro-Palestinian" encampment – I put it in quotation marks because most of its inhabitants could not find Israel on a map or name one single Palestinian leader – which was erected again on campus, one man was photographed dressed like a nukhba terrorist, in full gear including a face covering with only his eyes showing and a green Hamas headband. He was standing next to activists for trans-sexual rights. This strange alliance did not amuse me.

The progressives challenge much more than Israel, or the rights of Jews to a nation-state. I am not sure how many people who identify as progressives, truly hold these ideals, and how many of them just repeat them loudly, over and over again, to gain some kind of social sympathy. But those who do hold those views, no longer believe in the existence of "truth,” or that there are facts.

5 View gallery

Anti-Israel protesters camp out at Stanford University

(Photo: John G. Mabanglo / EPA)

I don't mean those who say that the truth is hard to find or think that courts are not always able to discover what is fact, or those who believe that ideas are perceived differently through different eyes.

I mean those who say unequivocally that there is no such thing as the truth. They are not interested in presenting facts to support their claim because they do not believe there is such a thing as facts, and they say so explicitly. They will condemn you for using the term “Jihadist,” regardless of the context, because feelings, theirs most of all, are more important than facts.

They don't believe there should be consequences to actions because they don't believe there should ever be consequences. There can be disagreement over everything because nothing is real. Life is a debate club. This is not an indulgence, or at least not only that, it is an ideology that calls into question the existence of an objective truth, whether attainable or not – as an intellectual concept.

4. Always walk the straight and narrow, what others say or write about you is not very important.

The fact that those I considered friends turned against me, brought with it a temptation to keep my head down. I don't disrespect those Israelis who chose that route and I understand them. At this stage, feeling ashamed of being Israeli, hiding any Jewish markings, or trying to adopt an American accent, could ensure a reasonable quality of life, even where the hatred for Israel is prevalent. But when I was faced with that temptation – to some extent, I tried to remember what I had learned from two of my teachers in recent years.

Attorney Shlomo (Momi) Lamberger, Israel’s deputy state attorney, used to tell his clerks that they should “walk in the straight and narrow,” when deciding whether to indict or drop the case. The only thing that matters are the facts and the law. It is easy to be tempted by what is in the press, what the Minister of Justice would say, and how advantageous to the career it could be, but when you consider those things you easily lose your way.

Justice George Karra would tell his clerks that no matter what is said or written about them, facts are more important. Making the right decision is more important. There is no reason to align with nonsense, even if there may be some public or social price to pay.

Those lessons were true for major decisions and much more so for personal ones. Whether to keep my head down or insist on being outwardly and proudly Israeli, even where it is uncomfortable.

These lessons are even more true when the heavy price for walking the straight and narrow would be that some American doctoral students would disapprove. Since October, I have learned that there is no point in keeping my head down, while the decision to walk the straight and narrow, and call things what they are, has value.

5. The solution to the crisis in the universities cannot come from the bottom but it could be resolved from the top.

The kids protesting on campuses worked hard to get into Harvard, Stanford, Yale, and Columbia. Most are not the "Vietnam Generation," even if that is the story they tell themselves. They are the equivalents of the kids who serve in the elite 8200 intelligence units or the Army radio. They worked hard and paid a great deal of money to get there, and they care about how they would graduate. They care about the opinions of those they look up to. They also care what their peers think. Most care equally about what the university president, the faculty dean, and their younger professors, think about them.

For many of them this current wave of protests could be a learning opportunity. The American universities highlight the importance of free speech in American culture, and the importance of the 1st Amendment to the US Constitution, which ensures the complete freedom of speech in the American political atmosphere. They cannot shut protesters up. That is true. But universities can and must educate their students. They cannot and must not prevent them from shouting out their demands to start an intifada or to boycott Israel, but they can tell them that they hold stupid positions.

If the presidents of universities would stop fearing their shadows, they could tell their students that they have a right to their stupid opinions but shouting them out would not make them any less stupid.

Professors cannot silence their students, but they can point out to them that those who express ignorant and unfounded positions with such certainty are failures of education.

An Israeli – I have found – cannot convince his American counterpart that Israel is not committing genocide, even if that claim is not supported by a shred of evidence. But if the president of the university looks the students in the eye and expresses a sincere disappointment that such unfounded views are being voiced, something may change for some of those students.

Advocating directly to young students, though it is done to a certain extent, is limited and organizations struggle to succeed. The solution, in my view, is to urgently pressure the presidents of the universities. University leaders and senior members of the faculty are older, more reasonable people who were raised in the 1970s and 1980s. They remember the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. They are liberal, but like Bill Clinton is. They respect Israel. They would not entertain the prospect of accepting the demands of the BDS that many of the students have been echoing.

Yotam Berger

Yotam Berger In private conversations with Israelis, they express their affinity for Israel. But their fear of their American students is much stronger than any kind of feelings toward their Israeli students.

The pressure should be on them. If they overcome that fear that prevents them from speaking their minds, they would be able to draw a line, which would then permeate to the students who want to participate in the pro-Palestinian festival, to be popular but want more, to be liked by people who are important for their professional lives.

If we do not use this opportunity, we will find ourselves soon, facing a new generation of deans and university presidents and they may not be positive toward Israel.

Yotam Berger is a doctoral (JSD) candidate at Stanford Law School. He has previously served as a clerk at the Supreme Court of Israel and as a reporter for Haaretz and Army Radio.