Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

It’s morning in Berlin, where Avigail Ben-Dor Niv has been living for the past five years. There, she co-wrote the horror drama The Malevolent Bride, and as a result, she got a little closer to religion, began her rabbinic studies, met a pianist who became her husband, and had two sons.

Now she is working on her thesis ("Dealing with angry women in the Talmud"). “Not many people know that I wrote the series with one hand on the keyboard and the other holding a baby,” she says.

What is the film and television industry like?

"Tough. The industry is a very masculine world, and I had to make compromises. I couldn’t be on set because the filming happened two or three weeks after I had a baby."

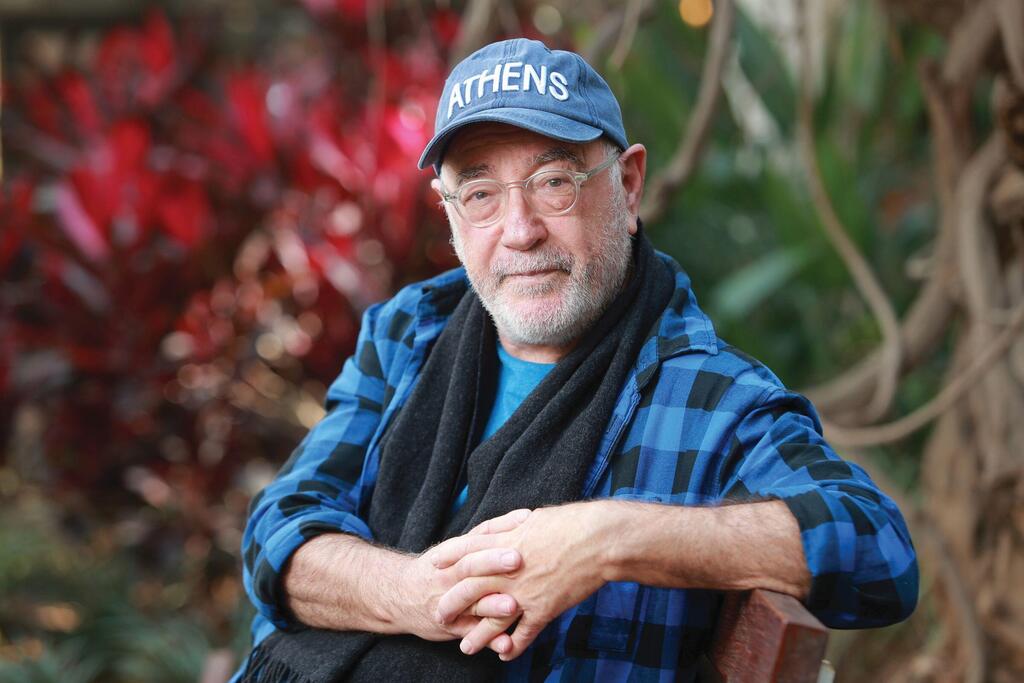

Avigail is the youngest of two daughters of Orna Ben-Dor, an esteemed director, and Kobi Niv, a screenwriter, writer, and critic. From a young age, she bears the names of both of them. “It was the most natural choice,” she explains, “They both raised me, and they both are responsible for me becoming who I am today."

She was born and raised in Tel Aviv and when she was four, her parents divorced. “I’m thankful they met, but I don’t think they should have lived together forever. Thank God we're not Catholic. It was a story that took us all a long time to recover from, and I have nothing to say about it. That’s their story, not mine.”

In high school, she majored in cinema and then did a year of pre-military service at a secular yeshiva. “It was an amazing year in which we studied Talmud from eight in the morning to two in the afternoon and then we treated at-risk children.”

After serving in the Israeli Air Force, she studied film at Sam Spiegel Film & Television School and worked as an editorial assistant for the second season of a series created by her mother.

“When I finished school, my mother told me, ‘I’m not sure you’ll find a job right away, go get a bachelor’s degree,’ and because I had no goal, I went to study Talmud and Jewish thought."

"I was the only student, I guess they really don't joke when they say it's "a one-student class'. The professors didn’t know how to handle me. The gap between school and life was funny, because on the one hand, I was working as an editor, and when the ratings came in the morning, we knew half a million people were watching our series, but then in class, we were three people."

How did your childhood look like in a house with two filmmakers?

"Cinema was everything, and I experienced the world through films. It taught me how to smoke, drink, and have a good time. From an early age, my mother took me to the editing room and asked me for my opinion. She was the best teacher I could ask for."

"My father also showed me films from a young age and was asking me 'what's wrong with the script?' You can't watch movies with him, because he has seen them all and he always whispers to people what's going to happen next. I am like him in that regard, when you are on the whispering side, it's fun, but when you are on the other side it's less fun," she says and laughs.

"When I had job interviews, my mother would say: 'Tell the interviewer I said hi.' I told her it was embarrassing. Maybe that's why I chose to be a rabbi, too, because it's a world where my mom can never send regards to anyone."

She moved to Berlin as part of a student exchange program, where she met Admiel Kosman, a professor of Jewish studies and the academic director of the Geiger Reform Rabbinical Training Institute in Berlin.

“One day, none of the students came to his Talmud class, except for me,” she recalls, “we started talking about Israel, and he asked if I ever thought about being a rabbi."

"I asked what a female rabbi was doing and as he described the role, I felt it fit me like a glove. I felt like my soul took a deep breath and got some fresh air. I went back to Israel and thought that rabbinic studies in Berlin were crazy because then Berlin was for me a city of sins and art and sexual promiscuity. Today, as a mother of two, I see the other colors of the city. When I came back to study, with no intention of leaving the country, I met my husband here and the children were born."

As someone who kept both her parents' last names, she did not seem to try to escape the family pedigree, but she did feel the need to prove that she was talented in her own right.

“In Germany, my name didn't mean anything to anyone, but it’s a name that bothered me in the first few years of my profession because I felt I was given a chance only because of it."

"Every time I had job interviews, Mom would ask, ‘Who’s interviewing you? Tell him I said hi. I would laugh, ‘Mom, I’m not going to go into the interview and say hi for you, it’s embarrassing.’ Even at Sam Spiegel school, when they called names out loud when they got to me they said 'say hello to the folks.' Maybe that's why I chose to be a rabbi, too, because it's a world where my mom can never send regard to anyone. The ideal rebellion.”

What did your parents think of you going to study Reform Judaism?

“My mother responded with a scream. I later found out that some sorcerer told her that her daughter was going to repent in the next two years. He didn’t read the cards correctly, I didn’t really repent in the classic sense. Maybe it was a scream of relief. My father is less involved in the decisions we make. We're grown-up kids. I later learned that my great-grandfather on my father's side was a Hasidic Sanz follower."

What did you know about Judaism before you delved into this world?

“I grew up in a secular home. On Passover, we would hide the afikoman and eat dumplings, but we did not read the Haggadah. It was an opportunity to sit together as a family and my grandmother would put challah bread on the table. My only true love was for Hebrew, so I dove into the Jewish texts because I wanted to understand [pioneers of modern Hebrew poetry and literature] Hayim Nahman Bialik and Shmuel Yosef Agnon. As a child, I never set a foot in a synagogue, and I’ve been to more cathedrals and churches in my life.”

For the past two years, she has been studying to become a Reform rabbi, studies that will also grant her a master's degree in Talmud. “I accompany people in their encounters with Judaism,” she explains, “if it’s burial, Shivah, or questions about existence and in the future weddings as well.”

And besides rebellion, how do you explain the choice of rabbinical studies?

"I wanted to enrich my identity. Living as an immigrant is also important in a person’s life, being a guest in a particular place allows you to see who you really are. I chose to be a rabbi because there is a real war against the image of Jewish people, and recent times prove that this is indeed a war. The Jewish canon does not need more grammar and commandments, but rather courage and a feminine voice.”

Her lifestyle includes lighting candles, going to the synagogue, and avoiding using her cell phone during Shabbat. "I support this idea that you need to rest and also let other people rest. You don’t have to sit in a coffee shop, it’s a day of rest. In a world where anything is possible, it's beautiful that my son can go through Shabbat without using his phone."

“I don’t put a hair cover, but when I’m doing holy things, including writing a series, for example, I do put a bandana on my head to keep the energies close to my brain, I don’t have any other explanation for this behavior.”