Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Jon Feder visiting the Inquisition Archives in Lisbon

(Video: Jon Feder)

On April 1st, 1582, the Inquisition burned my aunt Genebra da Fonseca to death in the central square in Lisbon, Portugal. She was my great aunt, ten generations ago, the sister of my 10th great-grandmother.

Read More:

She was by no means the last of our family to die at the stake. The da Fonsecas were a highly respected Portuguese Jewish family that included doctors, lawyers and merchants. They were officially “New Christians”, i.e. Jews who had been forced to change their faith. In practice, the family were Conversos, secretly cleaving to their Judaism.

7 View gallery

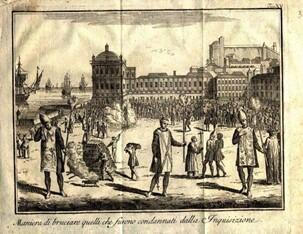

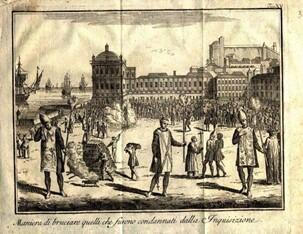

Auto-da-fé ceremony burning Jews at the stake at the Praça do Comércio, the main commercial square in Lisbon

Inquisition leaders reserved burning Genebra for a particularly “festive” occasion: The celebrations surrounding the coronation of the new king. My poor aunt, along with further miserable and wretched Jews, was “lucky” enough to be tormented to death at the central show honoring King Philip II of Spain, who was also crowned King of Portugal. The King even relayed the event in a letter to his daughters, Isabella and Catherine, in Madrid – even enclosing a ceremony program.

The horrific public punishment ceremonies carried out by the Inquisition were known as autos-da-fé, (“acts of faith”). Their role was clear: to demonstrate the force of the church and the Inquisition, intimidate the masses, and illustrate to the “New Christians” their certain fate if caught practicing their former religion. Needless to say, the torture, executions and punishment shows that continued through to the end of the 18th century efficiently eradicated the Conversos.

The Inquisition in Portugal was founded in 1536, 50 years after her Spanish sister, and for the same purpose: To all intents and purposes, cleanse the kingdom of heresy and all non-Catholics. The working method was similar: interrogations, forced confessions and harsh punishments. The Spanish Inquisition takes the lead when it comes to death, cruelty and causing suffering. Estimates number the death toll of the Spanish Inquisition at 30,000-300,000. The Portuguese Inquisition was less murderous and much more bureaucratic, systematically recording its activities.

The Archive of the Inquisition in Portugal, housed in a terrifying building in Lisbon, retains the minutes of 31,000 lawsuits conducted by the Inquisition in Portugal. Interrogations didn’t focus just on Jews (“New Christians”), but rather on anyone caught carrying out any religious practice that was not Catholic. Others tried included Protestants, Muslims and those suspected of witchcraft or “deviant” behavior.

1900 legal cases resulted in execution – mostly public. 95% of court cases in Portugal, however, were closed with “only” admissions of guilt and expressions of remorse. These “confessions”, usually obtained following a series of dreadful tortures, carried with them severe punishments: flogging, lengthy imprisonment, confiscation of property as well as being compelled to display the “disgrace” of their conviction in public by wearing degrading hats, etc.

The da Fonseca family aroused the suspicion of the Inquisition in its very early stages. Although the inquisitors claimed that the family were secret Jews, they struggled to collect evidence.

My 11th great aunt, Leonor Nunes, was imprisoned by Coimbra’s Inquisition in 1568. Her interrogation proved that she had secretly kept Shabbat and partially fasted on Yom Kippur and the Fast of Esther. Leonor confessed her “sin”, but declared herself a good Christian. It didn’t help. She was brought to court and charged with heresy.

The judges ruled that, although she outwardly kept Catholic practices, she didn’t truly believe in them. She was sentenced to prison and was forced, to the end of her days, to wear a “sambenito” – a tunic and a conical cap, denoting heretics. This hat of disgrace constituted an open invitation to anyone meeting her in public to curse and beat her. To the end of her days.

Christian nobles saved great-grandma

I am familiar with the minutiae of the story of my ancestors who attracted the attention of the Portuguese Inquisition, including that of my “Aunt Genebra.” Ironically, the main sources of information are the records kept by the Inquisition itself.

The da Fonseca family aroused the suspicion of the Inquisition in its very early stages. Although the inquisitors claimed that the family were secret Jews, they struggled to collect evidence as Aunt Genebra’s father, Dr. Lupo da Fonseca (my 11th great grandfather), was personal physician to Queen Catherine of Portugal, wife of King John III - granting the family a sort of royal protection.

Unfortunately, the esteemed doctor passed away in 1563 and the inquisitors felt liberated from the doctor’s royal connections, and started assailing the family.

Within months, his widow Beatriz Henriques was imprisoned and brought to trial before the Inquisition Tribunal. The interrogations and the trial dragged on, but she was ultimately forgiven. However, the Inquisition didn’t give up and interrogated her once again in 1574. They soon after also imprisoned two of her daughters, Maria (Sarah) along with her younger sister, Isabella.

Maria had recently married my 10th great-grandfather, Dr. Jeronimo Nunes Ramires, (Hebrew name: Abraham Curiel). Ramires was a highly acclaimed doctor - a professor of medicine at the University of Coimbra who authored works of academic research. The Inquisition allowed him to accompany his wife and sister on the journey lasting several days from the da Fonseca family home in Covilhã to the Inquisition prison in Lisbon in northwest Portugal.

As soon as the two women were jailed, Abraham Curiel returned to Covilhã and organized a rescue mission. He recruited a group of family friends and patients from his high-end clinic – all influential city aristocrats, all Christians (not New Christians of Jewish descent).

7 View gallery

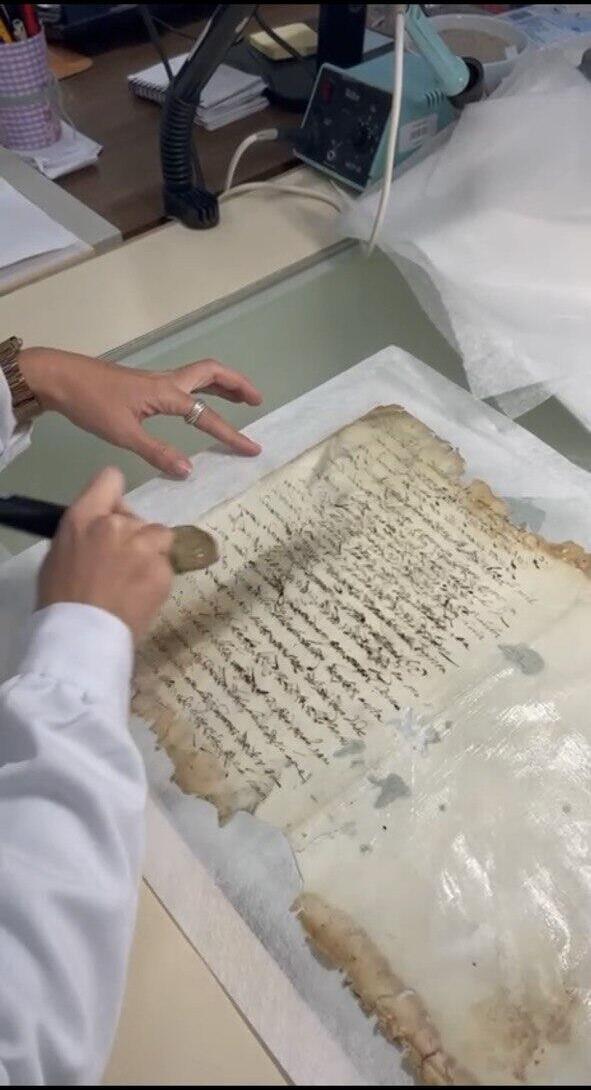

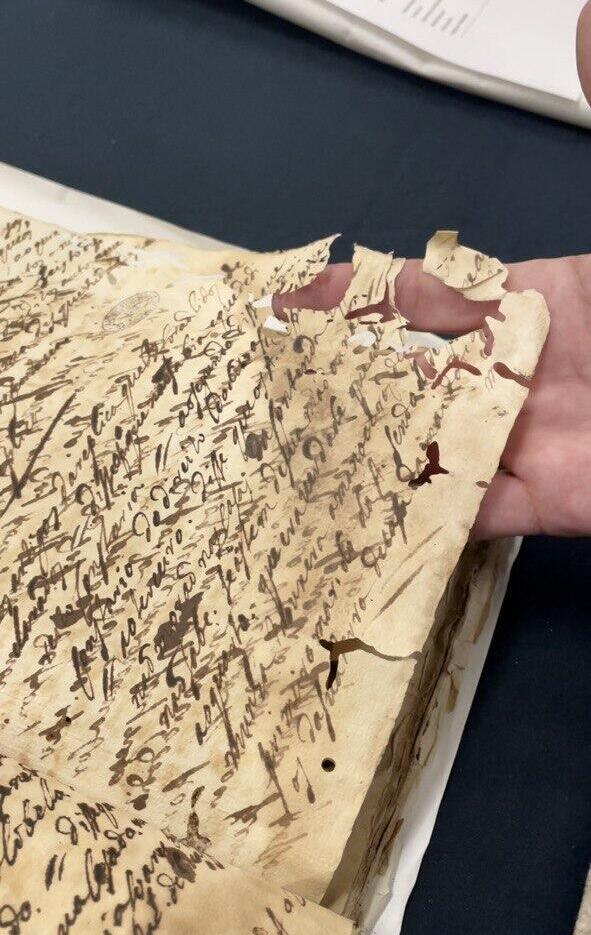

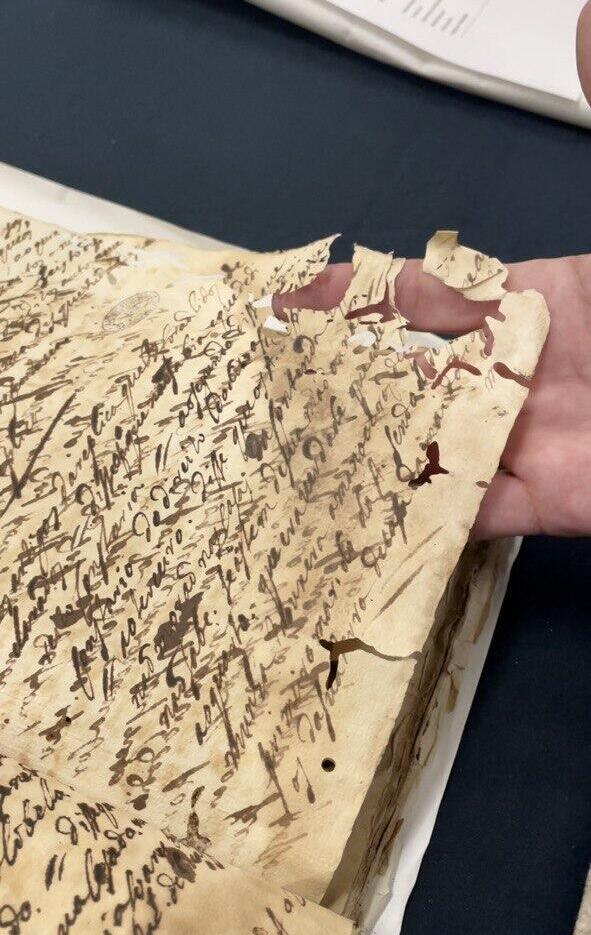

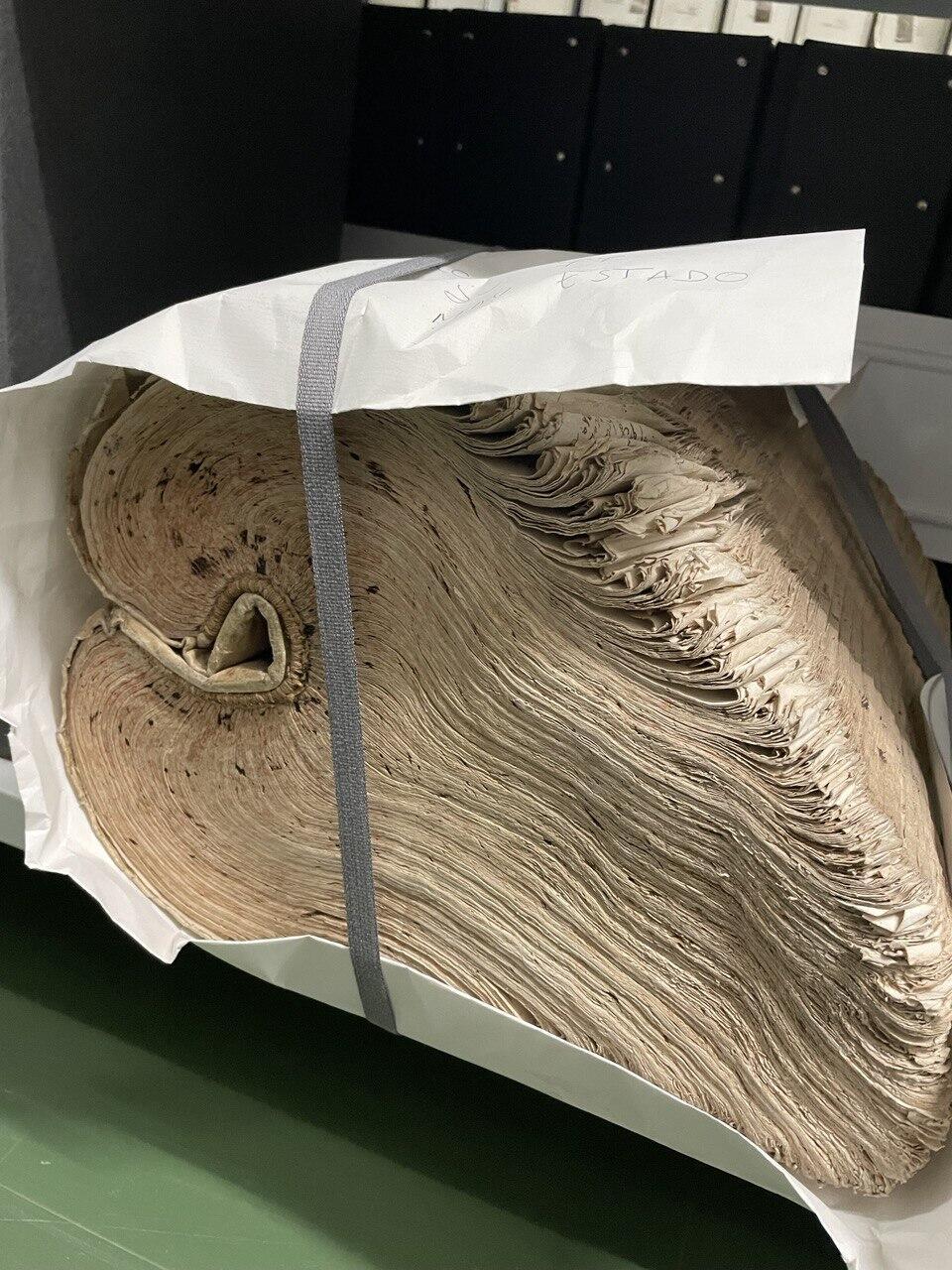

The old minutes in the Inquisition archive left to the ravages of time

(Photo: Jon Feder)

The delegation – comprised of two monks, two noblemen and nine women – set out on the three-day journey to Lisbon, where they presented themselves to the Inquisition. They each spoke in Maria’s defense, their testimonies fully documented in the Inquisition archives.

The witnesses adamantly contended that Maria and her sister were faithful Catholics who regularly attended masses and confessions, prayed to paintings of the saints and worked on Shabbat. Maria herself denied any connection to Judaism claiming she knew nothing about the religion. These efforts bore fruit and the sisters were released.

The case against Maria, her sister and mother, however, was not closed. The inquisitors sought out new testimonies, this time from two servants working in the family home, who testified that the family refrains from working on Shabbat and eats “Jewish food.”

The Inquisition sent investigators to spy on the family on Shabbat. The mother and daughters were prepared: They sat at the window facing the street, spindles in hand, industriously spinning yarn. The servants’ testimonies were dismissed and thanks to the pressure of the Covilhã noblemen, the Inquisition stopped harassing the family.

But not for long. Aunt Genebra was imprisoned three years later.

Over a mile of horror stories

These stories, the interrogations, testimonies, minutes from the trial and verdicts are all saved, detailed and organized into thick files – some disintegrating - in the Inquisition Archive in Lisbon.

Every interrogation is detailed, every testimony is fully recorded word for word. Interrogators rummaged through the family tree of each suspect, filling out precise lists of family members, their names, occupations, where they lived, to whom they were married, including aunts, uncles, cousins and filling in all the in-law clauses. Everything was filed and has been carefully kept through to the present day.

7 View gallery

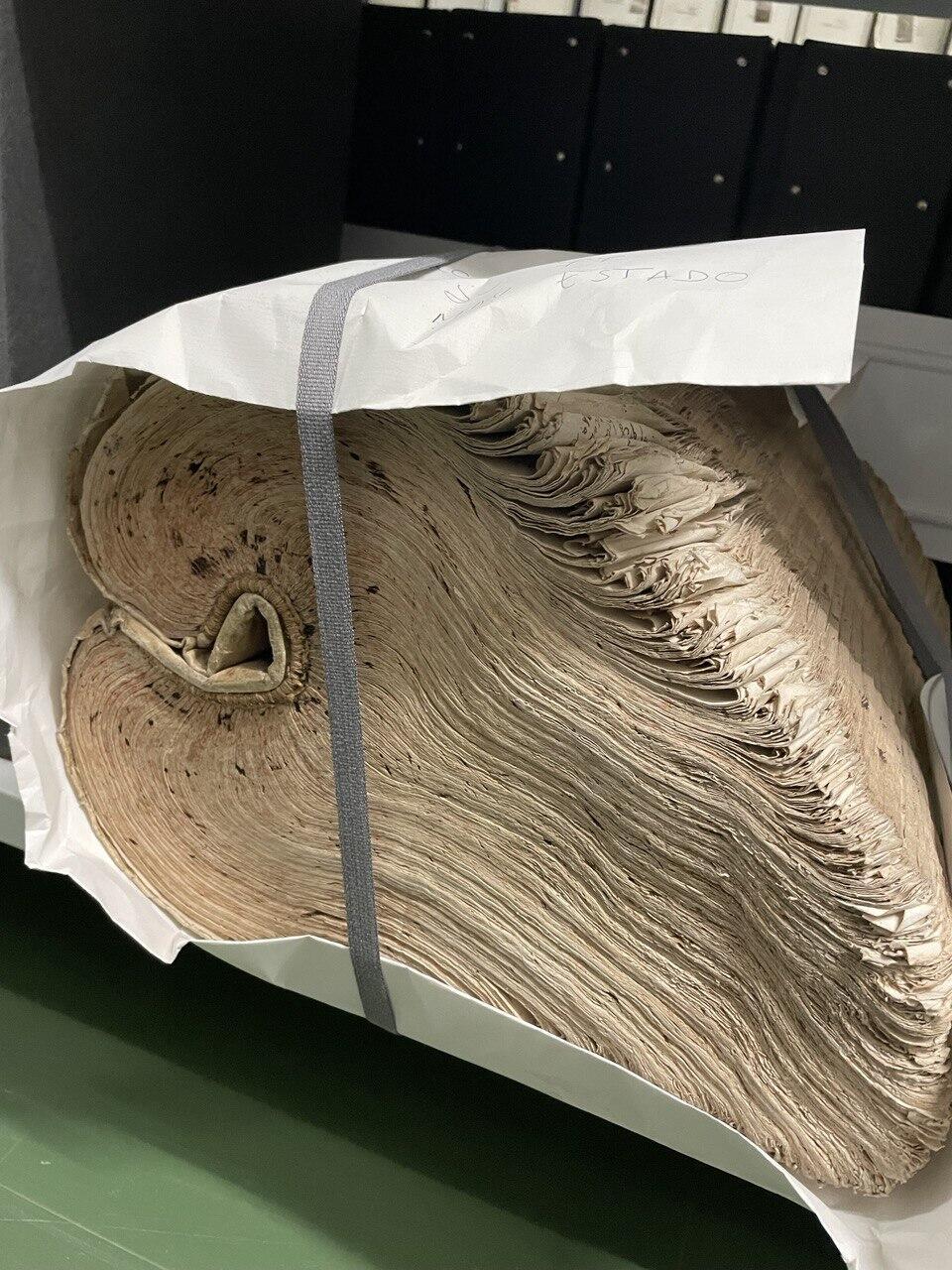

A pile of old Inquisition files stacked on top of each other at the Inquisition Archive in Lisbon

(Photo: Jon Feder)

Paradoxically, the Inquisition’s obsessive documentation has become the most reliable and comprehensive historical source for the history of the Jewish community in Portugal.

I recently toured Torre do Tombo, Portugal’s national archive, homed in a massive fortress-like building on the Lisbon University campus. Operating continuously since the 14th century, it ranks among the world’s oldest and most organized archives. For centuries, the kingdom’s documents were collected and filed.

In the 19th century, a few decades after it ceased to exist, the Portuguese Inquisition’s archives were transferred to Torre do Tombo. Documents were collected from the urban centers in which the Inquisition operated - Lisbon, Coimbra, Evora and Lamego – as well as from Portuguese colonies overseas. In small provincial courts, such as that in the village of Tomar, they were less diligent about documentation, but everything found there was transferred to Torre do Tombo.

Wading through these archives is an unusual experience. Endless shelves, holding thousands of files, folders and boxes - perfectly organized, sorted and numbered according to the locations of the tribunals, dates of trial and incarceration. There are over a mile of shelves, crammed with thousands of files of interrogations and trials. Each meter of shelves holds about ten thousand images (sheets of parchment, book pages, engravings), in total containing a vast volume of approximately 20 million pages.

Time is the enemy of these ancient documents. The pages are creased, torn and falling apart. The ink in which they were written has oxidized and has disappeared completely from some documents. Entire pages, some moldy, are stuck to one another. They’ve been attacked by moths, sacrum-eating beetles and termites. Only about a quarter of this treasure trove of documents has been conserved in reasonable condition.

In their emergency rescue operation, archive directors have managed to scan the 16th-century documents and have posted them online. The digitalization process, however, is progressing very slowly. The rest of the items in this unique archive are also in problematic physical conditions: about half of the Inquisition, documents require conservation treatment, and a further quarter are crumbling, in need of quick rehabilitation before being lost forever.

Left to the ravages of time

Without quick rehabilitation, this ram-packed treasure, documenting such a dramatic chapter in the history of the Jewish people, will likely be lost.

For several years, in the Torre do Tombo laboratory, Portugal’s National Archive has been conducting the initiative - unpreceded in its volume, complexity and technical aspects - of partially rehabilitating and saving what documents possible. The conservation of a single volume of documents entails 18-months' work of each laboratory worker.

Each volume is painstakingly taken apart by hand. Every page extracted is carefully unfolded, flattened and cleaned of bugs and moths. It’s then stuck onto thin, transparent, Japanese paper that prevents disintegration. After sticking and drying, the page is inserted into a press for 24 hours. The page is then returned to its original bundle of pages, and rebound into a book. The documents are then scanned and digitalized.

Digitizing the Inquisition Archive is an invaluable initiative. It makes the documents accessible to anyone in the whole world, and allows academic researchers and genealogy enthusiasts such as myself to view these centuries-old documents easily and directly.

The limited personnel and budgeting allocated by the National Archives and the Portuguese government do not do credit to the vast volume of documents in danger of extinction. The archive is dependent on donations from individuals and independent foundations.

Ruth Calvão, president Center for Jewish Studies in Trás-os-Montes: “The archive holds enormously unique importance for the Portuguese and Jewish people to address this tragic chapter of their common history together. The deterioration of the archive items constitutes a real danger of personal stories and testimonies of the injustices and atrocities that they endured disappearing forever. This would effectively erase the identities of victims and their families, and deny their suffering under the yoke of the Inquisition. A budget must urgently be found to immediately preserve the archive and enable its accessibility to the general public."

The bread that led to Aunt Genebra's death

One of the high points of my visit to the Torre do Tombo archive was when I was got to view the interrogation file of my Aunt Genebra. Even today, one cannot but be horrified by the tears, blood, abuse and suffering immortalized between the 500-year-old pages.

This is her story:

One day, in the winter of 1580, as Genebra, the young wife of the merchant, Gaspar Diaz, was baking bread in the family home in Covilhã when a neighbor came to visit. She looked at the baking dish intended for the oven, stuck her finger in the dough, and etched a large cross into it. A little short-tempered, Genebra erased the cross, saying she didn’t want to see a cross in her bread.

Taken aback, the neighbor went to tell her friends. The incident was the talk of the village womenfolk. Horrified by this heresy and blasphemy, the townspeople began demanding punishment. They were convinced that otherwise the Holy Spirit would harm the entire town, and its inhabitants would be afflicted by plague and deprivation.

If a New Christian was caught conducting any kind of Jewish practice in secret, but confessed and then recanted, although they were punished more severely, their sins were forgiven. On the other hand, those refusing to repent – branded by the Inquisition as “rebels” – were often treated particularly harshly

It wasn't long before a delegation of stern investigators from the Inquisition in Lisbon showed up in Covilhã to examine the incident. Genebra was beaten by her neighbors, imprisoned and accused of practicing Judaism in secret. She initially confessed, but later recanted her confession. According to the Inquisition, recanting a confession was worse than the actual act of heresy. So, Genebra’s judges sentenced her to the ultimate punishment – being burned at the stake.

The Inquisition's rationale was that if a New Christian was caught conducting any kind of Jewish practice in secret, but confessed and then recanted, although they were punished more severely, their sins were forgiven. On the other hand, those refusing to repent – branded by the Inquisition as “rebels” – were often treated particularly harshly and were frequently executed.

In Genebra’s case, the Inquisition didn’t have any real evidence that she practiced Judaism in secret. Apart from the story of erasing the cross in the bread, they had no proof of heresy, so Genebra was accused of witchcraft and sentenced to death.

The interrogation, testimonies and the minutes of the trial take up 251 pages of dense manuscript in a file on a shelf in the Inquisition Archive. Because the Inquisition was a horrific and precise organization, I know that Genebra was imprisoned on November 8th, 1580. A year and a half later, at a public auto-da-fé ceremony on April 1st, 1582, the official verdict was handed down: She was excommunicated, the family property was confiscated and she was burned at the stake.

As mentioned above, Genebra was not the last member of the family to be burned alive. In 1601, her sister-in-law, her brother’s wife suffered the same fate in Coimbra, our family’s city of origin, and an especially deadly Inquisition center.

Time is running out

“We don’t have the voices and images of the trials of the Inquisition, but the archive documents reveal the very details of the interrogations, the suffering endured by those investigated and sentenced,“ explains Dr. Silvestre Lacerda, Chairman of the Portuguese National Archive.

He clarifies that, although the Portuguese government began digitalizing the archive in 2007, the sheer volume of items means that the process is dragging on.

Fortunately, Porto’s Jewish community has come to the aid of the National Archives, making a generous donation (brokered by Israel’s former ambassador to Portugal, Rafi Gamzu) for the preservation of the documents. The donation enabled recruiting professional restoration personnel, and set in motion the restoration and digitization of 1,778 16th-century court cases against "Jewish infidels" in three centers – Coimbra, Évora and Lisbon.

This budget covers neither thousands of other court cases documented in further courts, nor those from the 17th and 18th centuries. The restoration of these documents awaits further donations without which, Dr. Lacerda stresses, it will be impossible to continue the project. He estimates that a further 4 million Euros are needed over the next three years to restore the documents on the verge of disintegration.

"The Portuguese Inquisition Archive ranks among the most important for researching the history of the Jewish People. If the severe damage caused to the documents in the archives continues, we’ll be guilty of losing significant information about this important chapter in Jewish history. With each passing day, more and more documents are damaged."

Historian, Dr. Joel Rappel, director of the Elie Wiesel Archive at Boston University who researched Inquisition trials, explains that: "Considering the overwhelming lack of direct evidence of centuries of history of Portuguese Jewry, the problematic physical condition of the documents in the files of the Inquisition trials is particularly worrisome.

I have been privileged to personally reach, with the help of Ruth Calvão, a descendant of hidden Jews. She agreed to photograph for me a prayer book belonging to Marranos, who for 400 years have, secretly and fearfully, maintained a different Jewish way of life. Their practices include lighting Hanukkah candles, conducting a Passover Seder with matza and lighting candles on Friday nights.

“Beyond a shadow of a doubt, the Portuguese Inquisition Archive ranks among the most important for researching the history of the Jewish People. If the severe damage caused to the documents in the archives continues, we’ll be guilty of losing significant information about this important chapter in Jewish history. With each passing day, more and more documents are damaged. We have a national duty to help save this vast archive."

Return to Judaism

Following long years of persecution, imprisonment and trials of family members, my 8th great-grandfather realized the time had come to flee Portugal.

Born in 1587, his name was Duarte Nunes da Costa (Hebrew name: Yaakov Curiel). In a complex and clandestine operation, he extracted his mother, brother and further family members from Portugal.

They made their way through Spain, France and Italy and then onto their final destinations. He settled in Hamburg, his brother in Brussels. They reverted to practicing their Judaism openly and using their Hebrew names and became leaders of the Portuguese Jewish community. Other family members remained in Portugal, living as Christians.

Yaakov Curiel and his sons, Moshe Curiel, in Amsterdam (my 7th great grandfather), despite fleeing Portugal and returning to their Jewish faith, became official representatives of Portugal’s royal family in the Low Countries and were even granted hereditary noble titles by the royal family.

For five generations, the family continued providing Portugal’s royal family with diplomatic and business services, never setting foot on Portuguese soil.

According to the Inquisition, even noblemen with royal connections, were heretics. Their only fate being death.