Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Experts working in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum's Preservation Department are laboring day and night to maintain and keep the museum’s aging displays intact in order to keep the memory of the Holocaust and the Jewish victims alive.

While many may experience a sense of shock and discomfort when arriving at the site and walking past its wooden cabins and barbwire fences, the museum’s staff tells Ynet that they have become desensitized to it over the years.

The importance of preserving items from that horrific period only grows with each year, as the number of living witnesses to the horrors of the Nazi regime continues to dwindle.

“The conservation labs were founded in 2003,” says Alexandra Papis, the department’s director. “We have a professional photography studio in which we take photos of exhibits before, during, and after their restoration. You usually don’t see much of a difference because preservation is about maintaining authenticity, not changing it into something new.”

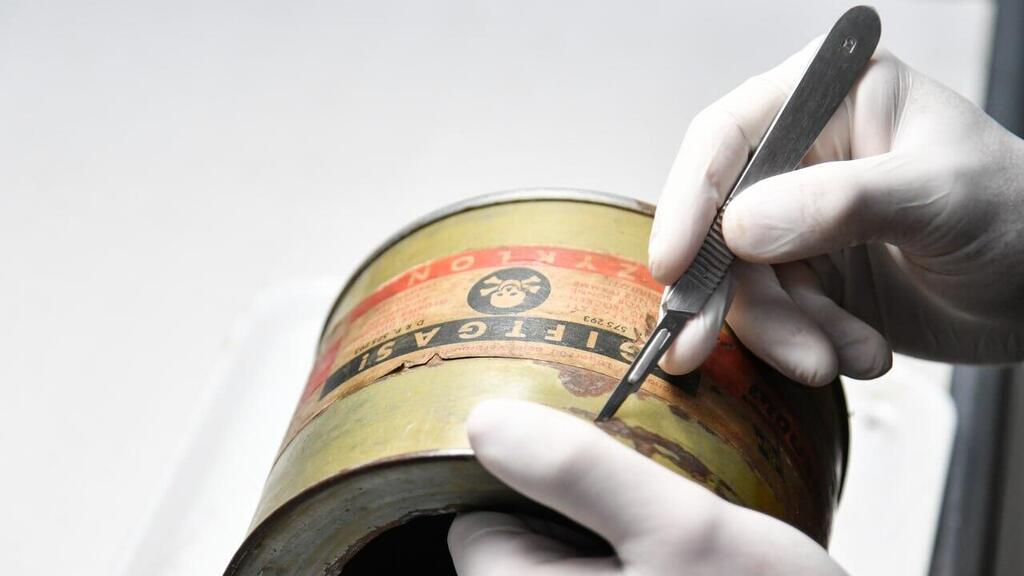

The museum's conservation labs employ a staff of 30 highly qualified specialists in landmark preservation, as well as specialists in various technical fields. One of the labs is restoring Zyklon B canisters, a toxic chemical agent used by the Nazis to kill Jews in the camp en masse.

“We touch it every day,” Papis says. “Every product has its own process to undergo. In this case, corrosion needs to be removed from the tin, which is intensive work. The issue with the canisters is that they were already conserved back in the 1950s, and were coated with a special lacquer to protect them. Now we have to remove it.”

Lab workers have to work wearing special gloves, and the preservation of a single canister could last up to three days. “We’re aware of the item’s history and what it was used for,” one Polish restoration expert says. “We don’t focus on it constantly because we have a job to do. We don’t throw away anything. Every item has a historical value and needs to be preserved.”

The museum collects items from all over the world. It recently received a donation of several articles from Polish families that held onto them for decades. “We receive donations from Poland, the U.S., Austria, Germany, and more. People are also donating documents.”

On one of the tables lies a rare exhibit: a wooden cradle of a Jewish baby. The museum only has four such items. “We decided we had to preserve the cradle. We’re dismantling it, cleaning it thoroughly, then putting it back together.”

Personnel working on the cradle say they feel like they are saving it from disintegrating. “We don’t add anything to the article. Sometimes we remove degraded material. We have experts for wood and metals, and we research every item to know what it’s made of.”

Papis says that “sometimes you can discover the history of the person who owned the item, like a name written on a shoe or suitcase. It allows for the museum to study the history of the people who died in the camp, and we strive to connect items with the stories of the people who owned them.”

Papis adds that finding more information about an item contributes to its preservation. “We still find things hidden in shoes, like documents. The exhibits tell us a story, and we can glean information from it. In one of the shoes, we found a newspaper clipping whereby we can infer where the person came from to the camp.”

In May 2022, the labs spotted the name Vera Verizhakova written on a shoe. The experts learned that she was born in 1939 and deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto near Prague in May 1942, at the age of 3.

She was then deported to Auschwitz on December 1943 with her mother and her two-year-old brother where they all perished. The family's father Max was also killed in the camp in July 1942.

During work on Verizhakova’s shoes, one of the conservators said that the name seemed familiar to her from a suitcase she worked on before. A brief investigation has found that the suitcase belonged to Vera’s uncle, who died in the Dachau concentration camp in April 1945.

“Thanks to thorough research we managed to cross-reference the girl’s shoe and the suitcase that belonged to her uncle,” says Hanna Kubik, a worker in the museum. “This is the second case in which such items were found to be connected.”

As the ground in the camp continues shifting, more hitherto hidden articles are still being found there. Workers are also finding items concealed in the walls of cabins currently undergoing restoration. Among the items found were an ivory switchblade, an iron key, a bottle opener, and a ring belonging to a Jewish woman. “Conservation takes time, it never stops,” Papis says.

The museum is set to launch a global campaign to preserve some 8,000 shoes belonging to children, most of them Jewish, a vast majority of whom were murdered in the former German Nazi death camp.

With the project estimated to last for two years, researchers are working to examine every single shoe before working on every individual item, some of which are in very rough condition.

In another room, some 3,800 suitcases carry names, addresses, and birth dates. These sometimes provide the only bit of information available about a person that was transferred to the camp but wasn’t officially registered by the Nazis and archived.

“That’s proof that people didn’t know what will happen to them,” Papis says as a conservator works on a suitcase nearby. “You don’t take a shoe brush with you if you know you’ll be murdered. They thought they were taken somewhere else.”

She adds that work on a single suitcase could take up to five weeks. “Time is our enemy, we can’t stop it, but we can slow it down.”

In another laboratory, experts are working to digitize documents belonging to prisoners in the camp or their families. “Every year we receive plenty of letters from all over the world,” Papis explains. “They check each letter. Only non-Jewish prisoners were allowed to write in German, and their letters were censored by the Nazis.

You can see letters with holes or eraser marks. Prisoners writing that they’re okay as part of the Nazi propaganda. These letters were also the latest ever written in the camp.”

Papis confesses that she and her staff often get emotional when handling the items. The camp also houses 6,000 toothbrushes and 110,000 shoes.

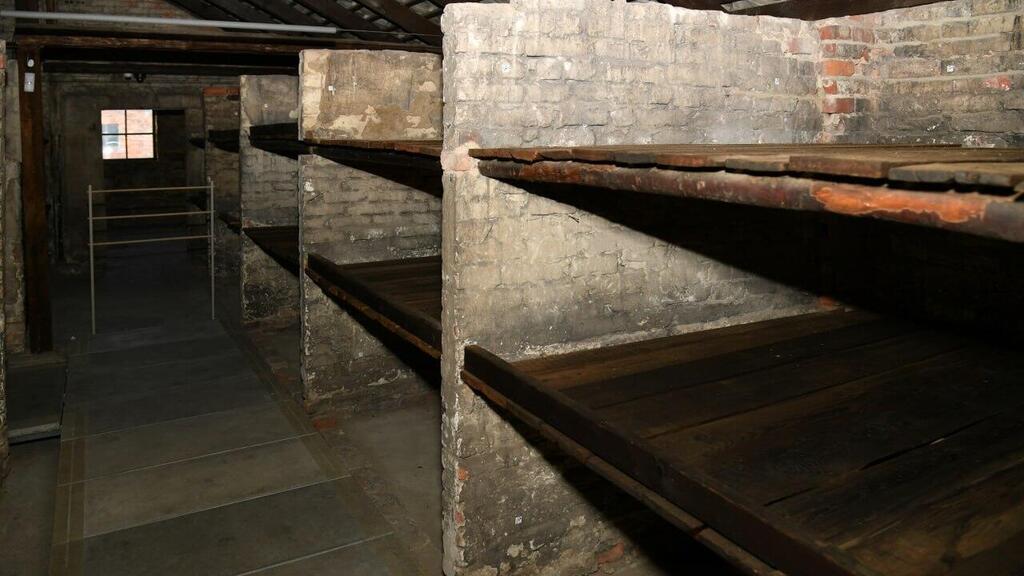

A large part of the conservation efforts focuses on the preservation of the camp’s dilapidated cabins that are degrading due to the elements. “We know that day comes that no witnesses will be alive, then this site will become a testimony,” she says.

“You walk past where people were murdered, where the Nazis attempted to destroy everything and to hide evidence. The cost of conserving two cabins is 12 million zloty (almost $2.8 million).”

Conservation works on the cabins began after years of research. “There are cracks in the cabins, the ground is muddy and the foundations are low. We had to remove the roof, preserve the natural colors of the building, remove bricks, and renew the foundations.”

Workers then removed the wooden boards used as beds in the barracks, coated them with protective materials, and placed them back.

“We have to hurry due to the poor conditions of the cabins. There’s also graffiti sprayed by visitors we need to deal with. We're currently renovating five cabins, it will take four years to complete. We're here to tell their true story,” Papis explains.

Works to converse the entire camp are estimated to be complete by 2043 with €175 million in funding provided by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation. Some 40 countries donate to the fund.

“The costliest thing to complete is the preservation of the brick buildings in the camp,” says Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation General Director Wojciech Soczewica.

“These buildings weren’t built to last over 80 years, and they’re collapsing. They weren’t built by engineers, but by prisoners. They were meant to be built, then destroyed when the Nazis finished their extermination.”

Soczewica adds the museum is also employing nine conservation experts from Ukraine who fled the Russian invasion of their country. “We give them a chance to work at their profession.”

“In the madness of Auschwitz, the most awful things are the gas chambers and crematorium,” he adds. “The importance of preservation is to keep evidence of the crimes. We found thousands of items hidden in the camp for 70 years.”

Soczewica explains that preserving evidence means memorializing the victims, and proving Hitler’s plan didn’t come to fruition. “Not many things remain from the people who died here. No photos, names, or property. Often all we find is a spoon, and that spoon remains a testimony of someone being here.”

“As Polish people, we want to care for every item, we know it’s our duty,” he adds. “This is our legacy. These camps are known as graveyards in Poland.”

European Jewish Association Chairman Rabbi Menachem Margolin lauded the conservation efforts in Auschwitz.

“Antisemitism isn’t gone, and Holocaust deniers are still trading Nazi memorabilia as if it’s something to be proud of. The conservation efforts in Auschwitz are an important educational tool to prevent another Holocaust," he said.