Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The soldiers serving at the Arrow missile defense interception center located at an Air Force base in central Israel liken their role to that of a goalkeeper in soccer: excelling throughout most of the game yet receiving attention primarily for the goals conceded.

"The Arrow system is the best in the world at intercepting ballistic missiles of this kind, especially given that no other system has faced such heavy barrages and achieved interception rates like ours," said Lt. Col. Eyal Frankel, commander of the 136th Arrow Battalion.

"Yet, as with any defense system, there are cases where it doesn’t succeed. Defense isn't airtight and we must always assume some threats will slip through. We use multiple defense systems to maximize interception chances, but sometimes it still doesn’t work."

How's morale after such incidents?

"Whether the failure is due to human or machine error, not completing the mission is tough. But we train our personnel to handle failure and understand it’s part of the job. Sometimes missiles fall because we decide not to defend certain areas.

“That decision isn’t natural for us — we can’t bear to see a missile hit. We have discussions to prepare the team for future challenges. It’s part of being a defender, like a goalkeeper who has to cope with conceding a goal."

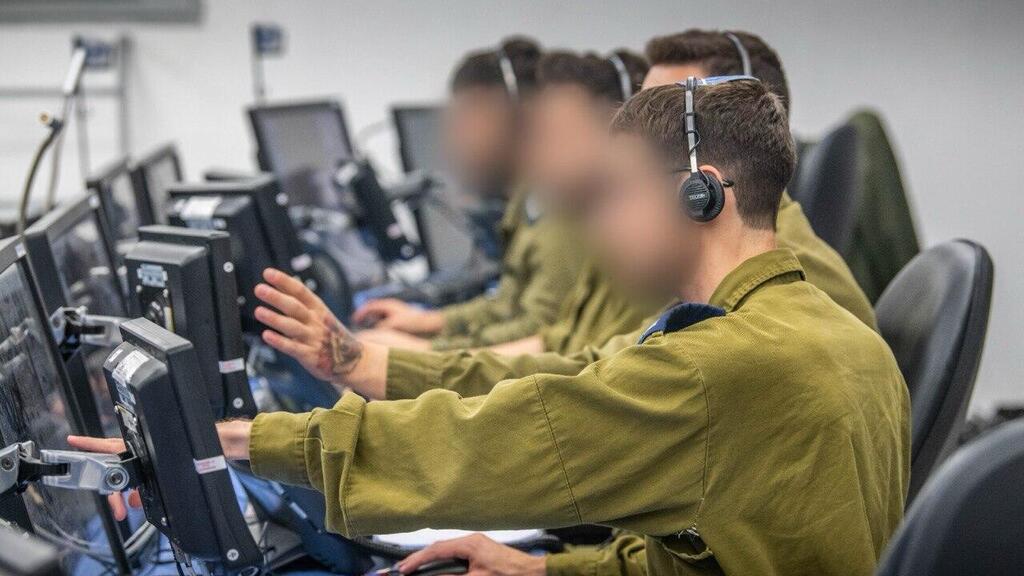

The Arrow interception center is one of the most classified sites in Israel, where life-and-death decisions have been made daily since the war began on October 7. While Israelis scramble to bomb shelters in their pajamas during nighttime sirens, rows of uniformed personnel sit in front of dozens of screens, surrounded by radios, lights and constant beeping.

Ultimately, one person decides when, where and how to press the button to intercept a ballistic missile launched thousands of kilometers away, often from Yemen or Iran.

Operators undergo two years of training and then work grueling 24-hour shifts, sometimes longer. "Nice to meet you, I’m R. from Ashdod," says a 21-year-old lieutenant wearing glasses perched on her nose.

Describing her role, she says, "I’m an interception officer. All of us have combat training — I was a combat soldier before coming here. I’ve since completed training that qualifies me for all the roles, from field operations to this position.

“We sit here for hours, making tough, high-stakes decisions. We’re responsible for intercepting ballistic missiles that leave the atmosphere. The system includes Arrow 1 and Arrow 2 and we work directly with other defense systems like Iron Dome and David’s Sling."

Why is combat experience necessary for this role?

"We have just seconds to make challenging decisions and it requires a combat mindset — knowing what it’s like to be called into action and function in combat within moments. It’s combat, even if it’s through a screen. It’s stressful but also exhilarating."

What’s exhilarating about it?

"Intercepting a missile over my home in Ashdod and then calling my parents to ask how they’re doing."

The Arrow battery commander, Maj. L., shared: "A few weeks ago, missiles were launched toward my home in Rishon LeZion, where my wife and baby live. From the moment the missile is launched and we receive the alert, we know exactly where it’s headed to strike. It’s more stressful than exciting.

“After my shift, I called my wife the next morning to ask how she was, and she replied, ‘You’re calling now? It happened in the middle of the night.’ I laughed. She, like many civilians, doesn’t understand what goes on behind the scenes and how much human involvement is behind every system decision — from the field to R. here operating the button."

Sitting nearby is Lt. A. from Nes Ziona, also an interception officer. "We’re experiencing events that haven’t happened in decades," he says. "My dad is a commander here on the base, also part of the system. What I’ve done in my relatively short service, he hasn’t done in 20 years. We’re not happy about the situation but it’s meaningful to be part of this."

A historic night

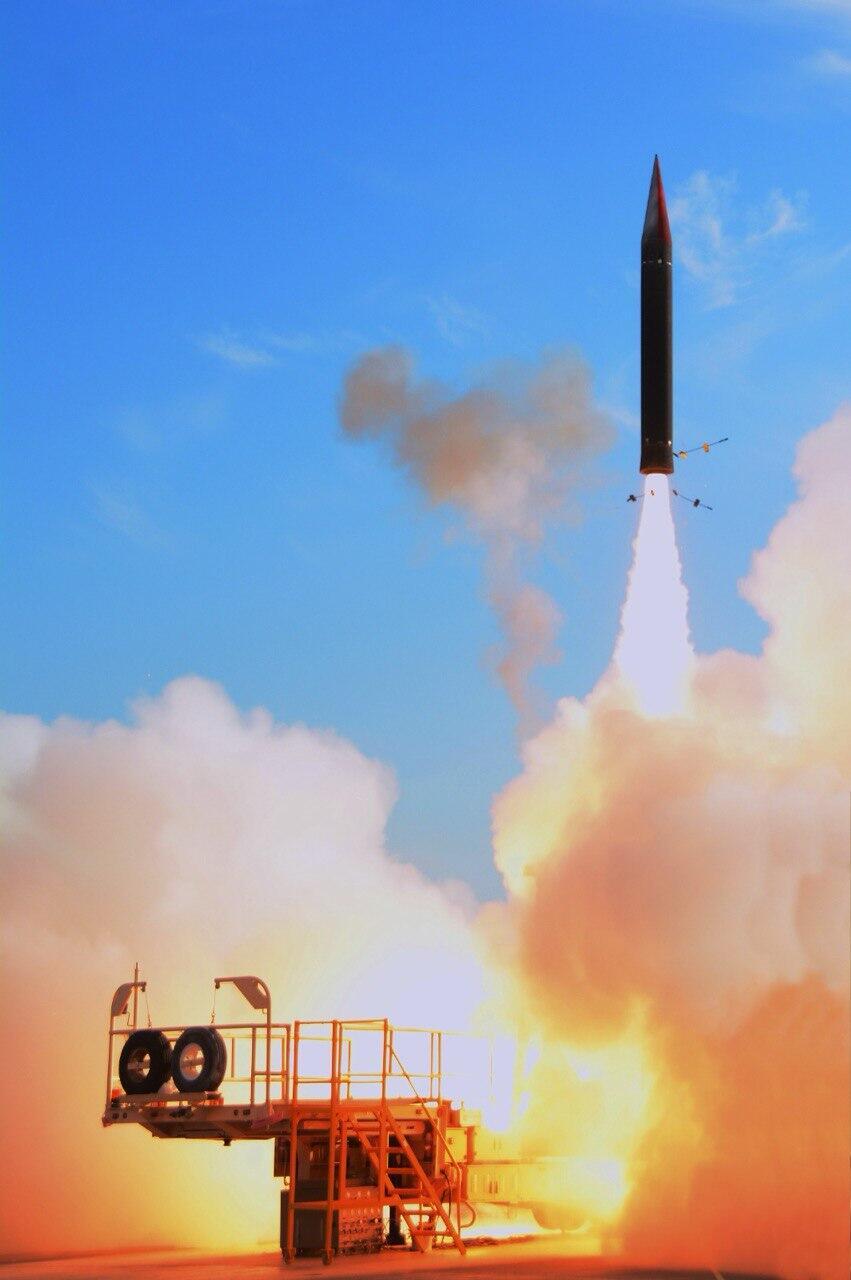

The Arrow system is a layer of Israel’s comprehensive air defense, which protects the skies from drones, missiles and rockets. The system is built on several layers: Iron Dome handles short-range targets and aerial threats, David’s Sling intercepts longer-range rockets and cruise missiles and the Arrow systems are designed to counter long-range ballistic missiles. During the war in Gaza, it intercepted launches from Iran, Yemen, Syria and beyond.

Entrance to the interception center requires removing any device that could be exploited by the enemy — mobile phones, smart watches, earphones, even the Ynet photographer’s camera. Walking through the fortified rooms, resembling safes, leads to a dimly lit control room filled with darkened screens.

On the surface, it seems like an ordinary room, but Lt. Col. Frankel explains that the site is so classified they had to prepare it specifically ahead of the journalists’ visit. "Don’t be disappointed," he asks.

On shift, the room hosts a commander and four interception officers seated at a row of computers. Behind them sits a reservist and Frankel proudly points to her: "She’s been with us for a long time, a mother of children who enlisted to support the system and hardly spends nights at home. Do you see the level of sacrifice here and how critical manpower is?"

The control room is responsible for implementing decisions handed down from the political and military leadership. These include protocols on which missile to launch, where to intercept and which areas are prioritized for protection. "These decisions come from much higher up following detailed discussions and they change hourly, not even daily," Frankel adds.

In a nearby room, a group of technicians in blue overalls manages the technological systems. From fixing a faulty computer button to addressing a technical issue with a deployed battery, someone must resolve problems immediately, as delays could impact an entire launch.

"There are many more rooms here," the commander continues without elaborating. "On the night of the first Iranian attack, this place was packed to capacity. It was a historic moment. Dozens of people, including senior commanders, were called in to operate all these computers. People think this system is purely technological. They don’t realize how much it depends on human input."

A nationwide unit

A tour outside the Arrow interception center reveals the quintessential image of an Air Force base: a pastoral, pristine and meticulously maintained compound. Senior officers live with their families just minutes away from some of the most operationally critical rooms in the Middle East.

Yet, the tension is palpable and the quiet is almost unnerving. Everyone is always on edge, always busy. Every uniformed individual seems to be heading somewhere on a mission.

"I'm Eyal Frankel, 41 years old, a father of four and battalion commander since August 2023, two months before the war," he introduces himself. "I've been serving in the Arrow system since 2004, growing through every role along the way."

Beside him sits his deputy, Maj. A, 31, and a father of two. He also lives on the base but barely sees home. "I took on the role last August," he shares. "I didn't grow up in the Arrow system but in Iron Dome. As part of the development process for deputy commanders and battalion leaders, we wanted to give them exposure to other weapons systems.

“The goal is to provide knowledge and learn from another system to become better commanders. This required me to learn Arrow from scratch, go through certifications and training and do it quickly — unlike soldiers who grow up in the system."

Beyond interception, Arrow soldiers bear another responsibility — issuing alerts to civilians. "To succeed, we need to master many professional domains," Lt. Col. Frankel explains. "A ballistic missile traveling from a distance carries hundreds of kilograms of explosives. It's simple physics: for it to reach Israel, it must go through certain processes while airborne.

“The result is that the missile arrives with fragments and debris, which makes it a significant challenge to intercept the relevant part of the missile mid-air."

The unit isn’t confined to just one base. The launchers, detection equipment, soldiers, technicians and support staff are spread across various points nationwide, from north to south. Divided into launch divisions, they’re equipped with mobile command and control vehicles and other resources to provide optimal protection.

"Right now, you're in a nice site, but that's not how it works in reality," Frankel adds. "To deploy effectively, you need to move constantly to adapt capabilities to the evolving scenario. The mobility of detection and launch systems creates a lot of fieldwork — day, night, weekdays, weekends, rain or heat. It's a massive challenge, especially for reservists who've been under emergency call-ups since the war began. It’s a complex operation."

One key figure in ensuring the unit functions smoothly is Capt. S., 25, the battalion’s logistics officer. "I’m a base-and-housing child," she admits. "My father is an Air Force officer and a retired lieutenant colonel. We just ate together in the dining hall. At headquarters, we support all the unit's sites nationwide.

“I don’t have a predictable day—not even the next hour. During the war, the unit doubled in size and we need to meet the needs of both regular and reserve forces — from lodging and gear like vests and helmets to transportation and all operational vehicle logistics. Without the drivers, we couldn't sustain the mission of providing protection 24/7. I might be in the north at 8 a.m. and in Eilat by dawn the next day. That’s what this entire war period looks like for us."

Hours upon hours of debriefings

A missile launched from Yemen or Iran can reach Israel within about 10 minutes. During this brief time, detection systems must identify it and map out its threats. Within these moments, countless decisions need to be made. The Arrow 3 interceptor targets distant, high-altitude threats, requiring launch decisions within seconds.

"You sit in front of a blank screen for an hour, two hours, 24 hours, a week, a month, even 20 years before the war, during which nothing happens. Then, in real-time, you have to be at peak readiness," says Lt. Col. Frankel.

"It's always on your mind. You go to sleep at 3:00 a.m., knowing you might need to jump into action and perform at your best within seconds. If it's stressful for civilians, imagine what it's like for those managing the interception process."

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

"Missiles launched from distant countries leave the atmosphere and even when intercepted, fragments can still fall toward Israel," he continues. "That’s why we must protect civilians even after a successful interception of the missile’s relevant components."

How do you feel about instances where missiles hit despite efforts?

Maj. A: "Events like these actually boost our motivation because they highlight the importance of what we do daily. In any case, after every success or failure, we conduct a series of debriefings. We spend hours analyzing what happened and how to improve next time. There’s no moment of rest."

What were the most significant events of the war?

Lt. Col. Frankel: "On October 3, we had the Arrow’s first operational interception in the Yemen front. Just like the Iranian nights of April 14 and October 1, we’ll never forget it. And it wasn’t just us — everyone involved in the defense industries and those responsible for developing this weapon over the decades was moved to tears.

“That missile turned out to be not so threatening because we proved we were ready. Seeing all the training and professional expertise materialize during nights of operational success is a unique feeling. If it weren’t about dangerous missiles, we might even enjoy it.”

"It’s not like we want missiles to be fired at Israel, but when it happens and succeeds, it’s a source of immense pride and satisfaction. The first time it happened, there was great excitement among those on duty at the interception console.

“But since then, we’ve gone through a lot. We all take part in these interceptions, whether it’s the technician or the soldier pressing the button. It’s the joint effort of many people that makes it work.

"We prepared for an attack from Iran and Yemen on October 7 too. We deployed defenses before we even believed it would happen. Now, we’re preparing for other threats we hadn’t even dreamed of.”